In June 2006, my wife and I flew west with our kids for what we figured would be our last big family holiday. I was bummed that I’d be missing the final round of the US Open, at Winged Foot, but when we boarded the plane I discovered that I could watch it on my seat-back TV. The leaders hadn’t even teed off.

Six hours later, Phil Mickelson arrived at the 18th hole with a one-stroke lead – and just at that moment our plane descended below 10,000 feet and the broadcast cut out. Good for Phil, I thought. He’s finally got his Open. The next morning, in our hotel room, I turned on Golf Channel to see how he’d wrapped things up – but the guy holding the trophy wasn’t him; it was some Australian kid. WTF! My first thought was that JetBlue had been showing a replay of an earlier round and that, like an idiot, I hadn’t caught on. But then I saw, on tape, how Mickelson had self-destructed: he sliced his final drive into a corporate tent to the left of the 18th fairway, then hit a tree, a greenside bunker, a school, a fire hydrant, a UPS truck, a cow, I don’t remember what else.

Architect Gil Hanse says “Tillinghast wrote how he wanted 18 east and 18 west to be like stair steps up to the clubhouse, so the green at the 469-yard 18th has some fairly aggressive levels. The biggest alteration we made was a restoration of the full false front, which is probably eight feet high. in 2006, that area was approach – it wasn’t part of the green.”

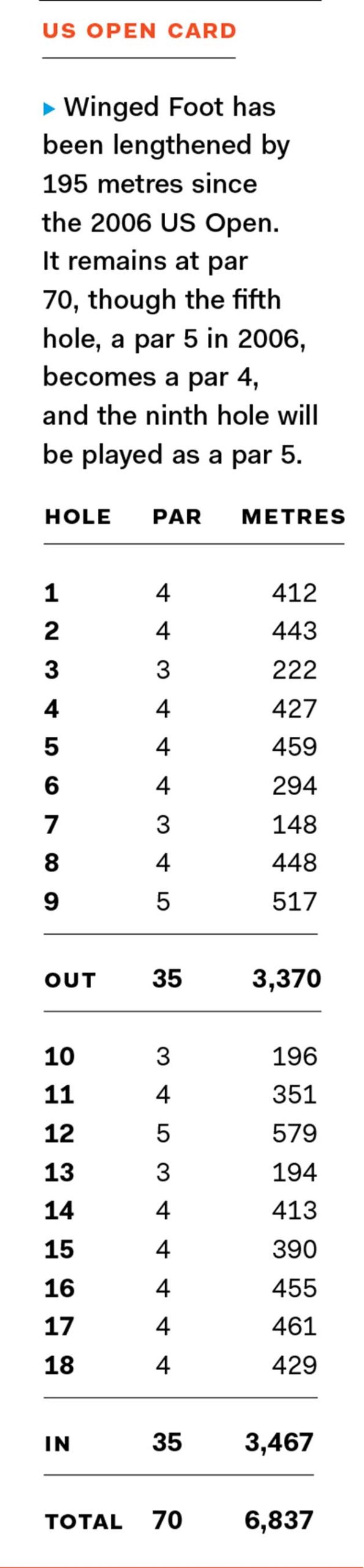

Rescheduled because of the coronavirus pandemic, the US Open returns to Winged Foot from September 17-20, for the sixth time since 1929 (Bobby Jones by 23 strokes over Al Espinosa, in a 36-hole playoff). The club is in Mamaroneck, New York, 30 kilometres north of Manhattan, and it has two courses, East and West. The US Open is played on the West. I played it this past November, on the day before it closed for the winter, and I had even more trouble than Mickelson. The greens had been aerified a couple of weeks before, but they were still faster and truer than any greens I’d putted on all year. In fact, Robert Williams, a club member in my group, said they would have to be slowed down for the US Open. “They’ve been running at 12 or 13 recently,” he said. “If you had them that fast under Open conditions, when the rough is thick and tough, they’d be almost unplayable. In the 2006 Open, they were certainly fast, but they were slower than they are today.”

And speed isn’t the only challenge. Winged Foot’s greens are contoured like those diagrams that physicists use to explain the curvature of space-time. You can hit a putt that looks pretty good for the first 50 or 75 feet, but then the ball rolls over a quantum anomaly, gathers speed, and ends up in a different part of the universe. On some greens, from some positions, a three-putt can seem almost heroic. And the greens are firm. During the 1974 Open (Hale Irwin by two over Forrest Fezler), the club used the eighth fairway on the East as a carpark. On Thursday night, a driver who’d had too much to drink got disoriented, exited in the wrong direction, and drove over the first green on the West, just hours before the second round was to begin. And the only reason anyone knew it had happened was that tyre tracks were visible in the grass on either side. On the putting surface the car had left no trace of damage.

On some greens, from some positions, a three-putt can seem almost heroic.

Williams’ father joined Winged Foot in 1959, another US Open year (Billy Casper by one over Bob Rosburg). He was 27 and single, and he’d played golf in college, and the club was looking for young members. Robert was born three years later, and three years after that his mother, whose name is now Kathleen Reilly, began taking golf lessons. Her teacher was Butch Harmon, then in his early 20s. (Butch’s father, Claude, was the head pro.) “The club in those days was very male-centric,” she told me. “It was a place where women came to eat, and we couldn’t wear shorts or pants, and our skirts could only be just above the knee. But Butch was wonderfully kind, and he would play with me – I couldn’t get over it. He was a dear. And now he’s all grown up.”

Robert spent his summers at the club, first in the swimming pool and then on the golf course. He rode his bike to the 1974 US Open, at which his mother worked as a volunteer courtesy-car driver. On Wednesday afternoon, her job was to take Sam Snead to the emergency room. He had played well during two practice rounds, but suddenly he felt ill. “When he got into the car he had his arm across his chest, and he said, ‘Kathy, I think I’m having a heart attack,’” she told me. She took him to the nearest hospital, in Port Chester. “Because I was waiting for him, they assumed I was his wife. They said, ‘Mrs Snead, come in.’” Explaining who she really was seemed too complicated, so she went in. Snead was sitting on the edge of the examination table in his underpants, still wearing his straw hat. The doctor said his heart seemed fine, but that he had cracked a rib. Reilly found a phone and called Winged Foot, then took him to his hotel.

Architect Gil Hanse says “the front of the green at the fifth hole, a 502-yard par 4 for the open, had been almost completely blocked off by a bunker that George Fazio added before the 1974 open. Tillinghast’s hole was wide open at the front – we and the club chose to not leave it completely open, but we did restore much of the accessibility, which gives players the opportunity to run a ball up there, especially from the rough.”

Major History

Majors haven’t always been as major as they are today. On the morning of the first round of the 1984 US Open (Fuzzy Zoeller shooting 67 in a playoff to beat Greg Norman by eight), Doyle Queally, whose father had joined Winged Foot 20 years earlier, was stuck with his mother in an unmoving line of cars on Fenimore Road, maybe a hundred metres from the club’s entrance. He recognised the driver of the car just ahead of theirs: Larry Nelson, the defending champion (by one over Tom Watson at Oakmont). “Nelson was clearly agitated,” Queally told me. “I got out and asked him when his tee-time was, and I told him he was going to miss it if he stayed in his car. I said I’d drive it up for him and give the keys to Eddie Nolan, the upstairs locker-room attendant.” Nelson thanked him, took his clubs from the boot, quick-marched up the hill to the clubhouse, changed his shoes, and went to the first tee. (He missed the cut.)

Majors were even less major in 1974. Winged Foot members put US Open bumper stickers on their cars in the hope of boosting ticket sales, and competitors were required to use local caddies, quite a few of whom were members’ sons. The players drew numbers when they signed in, at a big table in the clubhouse dining room, and the caddiemaster later matched the numbers with names. Doyle Queally’s younger brother Frank, who was 15 years old, was assigned to Bruce Summerhays – but he got to caddie for Jack Nicklaus, too, during a mini-loop before the tournament began. “Nicklaus pulled up in something like a Buick station wagon,” Frank told me. “It was 4:30 in the afternoon on Sunday, and registration didn’t start ’til the next morning, and the club was closed. I helped him take his bag out of the car, and he asked whether anyone wanted to caddie. I said, ‘Yes, sir, I do.’” Nicklaus played four or five holes, then chipped and putted on 18. “At some point, he said that the only way to play Winged Foot was to miss it short and try to putt uphill,” he said. “I’ve never forgotten that.”

Nicklaus forgot it four days later. During the first round of the tournament, he three-putted three of the first four greens, including the first, where he had a birdie chance from 20 feet directly above the hole. “The cup was right there,” he told a reporter 10 years later. “I hit a pretty good putt, and it rolled down there, about 25 feet away.” (In fact, it rolled off the front of the green – and this was at a time when the Stimpmeter reading probably would have been no more than 8 or 9.) “That’s about all I remember of the golf course,” Nicklaus continued. “I didn’t want to remember anything after that.”

Quality Design, From Logo to Course

Winged Foot’s logo is a winged foot (plus a pair of crossed golf clubs). It’s identical (except for the golf clubs) to the logo of the New York Athletic Club, and for good reason. Winged Foot was founded in 1921 by a group that consisted mostly of NYAC members, though there has never been a formal connection between the two clubs. Donald Trump stopped coming to Winged Foot long before he ran for president, although he continues to pay dues. Like the rest of the USA, the club has mixed feelings about the president. Shortly after the 2016 election, one member remarked: “No notice about one of our members being elected to the highest office in the free world? Jeez, we get an e-mail about who wins the Easter Egg hunt.”

Winged Foot’s founding members hired the golf architect A.W. Tillinghast to build them two big golf courses. Tillinghast was born in Philadelphia in 1876. His father owned a rubber company, and when Tillinghast was old enough to work there he earned a reputation as a lazy, unreliable employee. His father sent him to Scotland to play golf when he was 20, and he became friends with Old Tom Morris. Tillinghast finished 25th in the 1910 US Open. He drank too much. He had a temper and an ego. He once treated Leon Trotsky to lunch, in Mexico City, without exactly understanding who he was. He liked to travel in chauffeur-driven limousines, and he twirled the waxed ends of his moustache to such sharp points, the sportswriter Herb Graffis wrote, that they “looked like they could spike incoming and outgoing mail”. He was a poet:

He swung with all his might,

and then He swung with all his might again;

He swung four times, until in glee

He swung and almost hit the tee.

Tillinghast was also probably the greatest American-born golf architect of the first half of the 20th century. In a long, appreciative article in Golf Journal in May 1974, Frank Hannigan pointed out that four of the USGA’s 10 competitions that year were being played on Tillinghast courses: the US Junior Amateur (Brooklawn Country Club, in Fairfield, Connecticut); the Curtis Cup (San Francisco Golf Club); the US Amateur (Ridgewood Country Club, in Paramus, New Jersey); and the US Open (Winged Foot). Hannigan’s article was titled “Golf’s Forgotten Genius.” No one would call Tillinghast forgotten now. He not only designed the archetypal US Open course, he designed it three times, at Winged Foot, at Baltusrol, and at Bethpage Black (where he collaborated with Joseph H. Burbeck, the park superintendent).

My grandfather played his golf on a Tillinghast course: Indian Hills Country Club, in Mission Hills, Kansas, a suburb of Kansas City. My father and my brother (along with Tom Watson and Gay Brewer) played much of theirs at another: nearby Kansas City Country Club. And one of my favourite munys anywhere is a third: Swope Memorial Golf Course, in Kansas City’s largest public park. Recently, I scanned a list of the 260-odd courses that Tillinghast designed, redesigned or contributed to, and was amazed at how many I’d played and loved, sometimes without realising they had a connection to him – among them Sleepy Hollow, Philadelphia Cricket Club, Country Club of Fairfield, Brackenridge Park, Quaker Ridge (next door to Winged Foot) and Saxon Woods (virtually next door to Quaker Ridge), as well as all the other courses I’ve mentioned already. The man got around. Even so, he died broke, in 1942, at the age of 66.

Architect Gil Hanse says: “in previous opens, the ninth was played as a par 4. we were able to add a new back tee to play it this year as a 565-yard par 5, because with the green’s restored size and sharp roll-offs it was more conducive for a wedge approach than a long club. that cross-bunker short right of the green now serves as a hazard for the second shot.”

Tree Removal: Addition By Subtraction

The first time I played Winged Foot West, in 1994, I didn’t like it one bit. There were so many trees overhanging the fairways and greens that when I thought about my round later I remembered the course mainly as a succession of dark, endless, leaf-lined tunnels. To avoid the branches and the groves of immense trunks, I had to hit my tee shots very, very straight – tough to do because I knew I also had to hit them as far as I possibly could to have a chance of reaching anything in anything. Winged Foot’s members at the time viewed the trees not as a problem but as a sacred trust. They had just published an updated edition of their official club history, and more than half the text consisted of loving descriptions of individual silver maples, honey locusts, dawn redwoods, and shagbark hickories, many of them labelled and located on full-page maps of the holes.

Growing forests on golf courses began to fall out of favour not long after that. By the late 1990s, oaks and beeches that had been saplings when America’s most venerable courses were built had grown into monsters. They blocked sunlight, hogged water, impeded breezes, smothered greens, and necessitated the invention of the International Leaf Rule; they also acted like rogue course designers, reshaping play in ways no architect could have intended. Tillinghast loved trees, and he believed they were important design elements. But trees grow, and they close in, and they reproduce – and at Winged Foot and many other clubs the problem was exacerbated in the 1970s by a USGA-supported fad for filling empty spaces with ornamentals.

Growing forests on golf courses began to fall out of favour not long after that. By the late 1990s, oaks and beeches that had been saplings when America’s most venerable courses were built had grown into monsters. They blocked sunlight, hogged water, impeded breezes, smothered greens, and necessitated the invention of the International Leaf Rule; they also acted like rogue course designers, reshaping play in ways no architect could have intended. Tillinghast loved trees, and he believed they were important design elements. But trees grow, and they close in, and they reproduce – and at Winged Foot and many other clubs the problem was exacerbated in the 1970s by a USGA-supported fad for filling empty spaces with ornamentals.

During the past 20 years, Winged Foot has done what Oakmont, Olympic, Medinah, Chicago Golf, National Golf Links and dozens of other great old golf clubs have done: cut down thousands of trees. (You can flip back and forth between aerial photos of Winged Foot today and Winged Foot as I first played it by using the historical imagery function on Google Earth Pro.) Removing trees has revealed features that foliage had gradually obscured. The golf architect Gil Hanse, who recently directed a major, multi-year restoration and renovation of both courses, told me, “The contour changes at Winged Foot are much more subtle than they are at courses with dramatic landforms, like Shinnecock Hills or Augusta National, and when the course was cloaked by trees you never got an appreciation for them. Now you can pick up on the way Tillinghast routed the holes and propped up the greens, and you can observe his fingerprints on the land.”

On the 10th hole – one of the most celebrated and feared par 3s in the world – Hanse and Stephen Rabideau, Winged Foot’s superhuman superintendent, removed 15 mature hardwoods from undulating ground to the left of the putting surface. Those trees and their shadows had made the entire green complex appear narrower, flatter and significantly less interesting than it did when Tillinghast created it.

Neil Regan, who is Winged Foot’s club historian, told me, “Now that the trees are gone, you can see that the topography of the green actually starts 50 yards short left. The ground feeds in from there, and the same thing is true on the right. Tillinghast’s mantra was blending. For him, the approach to any green was part of the green itself, and it began far out in the fairway. He called it ‘the gateway to the green’.” Hanse and Rabideau also rebuilt every putting surface, to improve drainage, re-create lost contours, and restore original sizes and shapes. (Some greens had shrunk by more than two thirds.) Their first step was to remove and preserve all the sod. When they put the sod back, Rabideau’s crew applied top-dressing to the seams with pastry bags they’d borrowed from the clubhouse kitchen.

The clubhouse received major attention, too, inside and out. Tillinghast worked closely with the building’s architect, Clifford Wendehack, whose book Golf and Country Clubs, published in 1929, is still viewed by many as the bible of clubhouse design. They wanted Winged Foot’s clubhouse to appear to be rising out of the golf courses, and to make sure they got it right they selected its site before Tillinghast had laid out any of the holes. Wendehack used local stone, much of it from the property, and Tillinghast shaped the ninth and 18th greens on the West (and the 10th and 18th on the East) so that from their fairways they appeared to run all the way up to the building’s walls. That effect was lost in later years. Regan said, “What would happen is that committees would say, ‘Wouldn’t a tree be nice here, and wouldn’t bushes be nice there?’ Then they’d add a big hedge, and all of a sudden the first thing you could see was a second-floor window.” Most of the original sightlines have now been restored.

Regan is the curator of Winged Foot’s (very non-public) historical archive, which fills two connected rooms on the top floor of the clubhouse. He was reluctant to give me a tour, because, he said, during the renovation those rooms had become a dumping ground for framed pictures and other items that no one knew what else to do with. Even in its temporarily cluttered condition, though, the rooms are a golf hoarder’s dream. How about this photograph of a grumpy-looking Old Tom Morris standing in front of his shop in St Andrews, taken by Tillinghast in 1897? Or this bobbysoxer-flavoured poster promoting the 1957 US Women’s Open (Betsy Rawls over Patty Berg by six, on the East, after a scorekeeping screw-up by Jackie Pung and Betty Jameson)? Or this newspaper cartoon from the 1920s about a day when Babe Ruth was feeling too ill to play baseball but manfully finished 45 holes at Winged Foot and was upset that no one wanted to “make it a day” by playing nine more?

As much cool stuff as the archive contains, though, Regan is haunted by cool stuff it doesn’t – including plasticine scale models of all 36 of Winged Foot’s greens, which Tillinghast made while working on the courses. (A club manager found them in a storage room, and, anticipating Marie Kondo by many years, felt no spark of joy and threw them out.) Still, the collection is extraordinary. Among countlessly many other treasures, it includes photographs, drawings and diagrams that ended up playing a major role in Hanse’s restoration. Especially useful was a wood box filled with stereoscopic slides of Bobby Jones chipping onto the 18th green in the late 1920s. The slides provided three-dimensional proof that Tillinghast had intended that putting surface not only to be significantly larger than it had become but also to include a deeply concave swale near its leftmost edge. During a major renovation 35 years ago, George and Tom Fazio flattened the swale because they thought its slope was too severe.

It’s back.