Hidden in the highlands of Scotland is a mysterious mountain valley inhabited by portsided golfers

Our series marking the 50th anniversary of Australian Golf Digest and commemorating the best literature we’ve ever published continues. Each entry includes an introduction that celebrates the author or puts in context the story.

Dudley Doust, besides having a wonderful name for a writer, possessed the multifarious talent to back it up. He was born in Syracuse, New York, went to Rochester University before transferring to study journalism at Stanford, became a foreign correspondent for Time magazine, covered revolutions from a mud house in Mexico, married a British painter, and settled in Somerset in the south-west of England, where he replaced Henry Longhurst as the golf correspondent for The Sunday Times. He was a student of the Tom Wolfe school of writing and favoured stories with deeper meaning and surprising denouements.

I met Dudley for the first time on an extended trip to the UK for the 1982 Open Championship at Royal Troon. I was soon to be named the features editor for Golf Digest at the age of 26, so desperate for story ideas. Dudley told me about a trip he had taken near Inverness in Scotland on the way to a cricket match, his preferred sport, in which he stopped at a golf course in Badenoch. He was looking at the wall of framed pictures in the clubhouse when he noticed that nearly every golfer was holding a left-handed club, which led to some questions. “I’d like to do a story for you about this Land of the Left-handers,” he said in the press tent at Troon, and the assignment was struck.

As sometimes happens, the story didn’t get done right away. I’d see him occasionally at the Majors and inquire about how it was going, and he promised me a draft shortly. By the end of 1984, I’d become the editor of Golf Digest and really put the pressure on my friend to deliver. Finally, it arrived the next year, a long gestation period, and was published in October 1985. As you’ll read, the origin of the story was slightly different from the pitch; I take it that his conversation with a London doctor might have precipitated his layover in Badenoch, but the piece had his characteristic twists and texture. – Jerry Tarde

The road runs south from Inverness, climbs into the Monadhliath Mountains and plunges through forests pungent with pine trees. The valley of the River Spey opens round you, flat water meadows and birch trees, and a sign appears by the road: you are entering the District of Badenoch.

Badenoch. The Scots accent the first syllable and dwell gutturally on the last: Bay-de-nochhht. The word means “drowned land” in Gaelic; back in the 14th century, a local laird known as The Wolf of Badenoch brutishly held sway over the district. It is now fine deer-stalking country, with Britain’s best ski slopes near to hand, but to me “Badenoch” means one thing alone: The Land of the Left-handed Golfers.

I first heard of this mysterious district from a left-handed veterinarian named Peter Stuart, an expatriate Scot who lives near London. A stalwart of the Left Handed Golfers’ Society of Great Britain, Stuart twice had won its coveted Quaich Bowl, a silver replica of a vessel owned by Charles I, which is said to be the oldest golf trophy for left-handers in the world. Remarkably, Stuart considered his left-handedness to be quite – well, unremarkable.

“I don’t feel I’m a freak,” Stuart had said. “I come from the District of Badenoch in the Central Highlands, which is sort of a left-handers’ Brigadoon. I’d say about 40 percent of the golfers up there are lefties.”

Stuart’s casual remark dropped like a bomb. After its concussion had subsided, it called to mind some remote, inbred people, “Some mysterious mountain valley, cut off from the world of men,” as H.G. Wells wrote in his story “The Country of the Blind”.

Forty percent? The number seemed amazing. Lefties make up only about 11 percent of the population of Great Britain but, according to club manufacturers, only about 6 percent of the golfers. What’s more, judging from my left-handed American childhood (where for years I made do with only a cream-shafted, left-handed Bobby Jones 5-iron), southpaw clubs must surely have been hard to come by a half century ago in Britain. Stuart brushed aside the assumption. “Not at all,” he said, imperiously. “They cater to lefties in Badenoch.”

For my purposes, Badenoch meant Kingussie (population 1,178) and Newtonmore (population 1,010), a pair of villages that straddle the River Spey and huddle in the shadow of the steep, rugged rock, Craigdhu. They are physically joined by the clear, pebbly river and the Inverness–Glasgow railway line. More important, they are separated by centuries of bitter rivalry in a game called shinty. This game, indigenous to the Highlands, was to loom large in my new obsession – to solve the mystery of Badenoch’s left-handedness.

In the interest of scientific objectivity, my first stop there was at I. & J. Gunn, Gents’ and Youths’ Outfitters, in the High Street of Kingussie. The proprietor, John Gunn, not only had held the Kingussie club title 18 times but was right-handed as well.

“I think we accept left-handed golfers more readily here than they do in any part of the world,” Gunn said in the tolerant tones of a man who might allow his daughter to marry a southpaw. “Growing up in Kingussie, I was the odd man out. I played in a foursome with three lefties, good middle-of-the-road players – 4 or 5-handicappers – but not much better than that. At Kingussie, there are two or three members, all natural right-handers, who learned to play golf left-handed because left-handed clubs were the only clubs they could get. Left-handed clubs were passed down, father to son.”

As Gunn spoke, it slowly dawned on me that the mystery might be solved then and there. Perhaps Scottish fathers were too “mean”, as they say in Britain, too stingy to buy their sons conventionally sided clubs. If the sons chose to take up the game, they therefore were doomed to do so from the port side.

It was an intriguing notion but, on reflection, an unworthy one. Stingy or not, why would the fathers or indeed their fathers have owned left-handed clubs in the first place? “Have a word with the chaps at the club,” Gunn said. “To get there, go back through the village and turn left.”

Kingussie is a charming little course, only 5,504 yards long with a par of 66, that lies on interlocking shelves of hills above the village. First built in 1890, it was redesigned in 1906 by the legendary Harry Vardon, who by then had won four of his six British Opens. Vardon, of course, was right-handed, and there’s the rub. He plainly had no sympathy with his left-handed brethren. The holes were strung together, prettily enough, through heather and handsome stands of birch trees and larches. But they travel in a clockwise direction and, as any paranoid lefty who slices knows, that means trouble.

Take Kingussie’s course and its card. For starters, a deep gorge runs down the left-hand side of the opening hole, a 210-yard one-shotter called Craig Beag. The “local rules” on the card, furthermore, are shot through with such remarks as out-of-bounds being “to the left” and “the sandpit to the left of the 6th (Shepherd’s Hut) is a hazard”. Not once does the word “right” appear in these punitive rules.

Still, if you steer down the right-hand side of the fairways, Kingussie is a delightful holiday course, where, in the depths of summer, you can play well past 10 o’clock at night. It also is inexpensive; visitors are welcome at $8 a day, $35 a week, and on that July afternoon last summer, there were only nine golfers in view. Judging from the bright gloves they wore on their right hands, four of them were lefties. Clearly, there was plenty of room.

“If you go out in the afternoons you’ll nae see a dozen people,” said the club secretary, Norman MacWilliam, who met me in the small, wood Edwardian clubhouse. “If you’re a foursome, you’ll probably need three hours to get round.” To him, three hours seemed an unconscionable time for a round of golf.

On the wall behind MacWilliam hung a small period photograph, circa 1913, the stylised sort you find in clubhouses throughout Scotland and, indeed, Britain. It showed three members in cap and vest, stiffly posed behind the 18th green. The photograph hardly warranted a closer glance yet, surely, there was something odd about the picture. Suddenly, it came clear: all three men were holding left-handed golf clubs. What is more, the greenkeeper, standing beside them, was holding his mower handle in his left hand. Alan Dawson, who with a 4-handicap is the best lefty in the district, clattered up in his golf shoes. “We have to point that out to our visitors,” he said. “Even left-handers don’t readily notice it.”

I certainly hadn’t noticed it on my first visit to the club. At that time, in 1975, I was in blind pursuit of statistics. The secretary at the time, Jock Menzies, now dead, had provided them. He had ticked off the members’ names from the club ledger – holding his pencil in his left hand.

The statistics had more than supported veterinarian Stuart’s figures. Of the 40 valley-born members at Kingussie, 23 (or 57.5 percent) had played the Royal & Ancient game from the port side. “That doesn’t count the three other members we will have to put in the ‘don’t know’ category,” Menzies had added. “They play cack-handed, that is to say, they hold the club with the left hand down the shaft and swing it right.”

I had taken a similar survey a few miles down the valley at theNewtonmore club, which, as though sharing a feeling of embattlement, has reciprocal membership with Kingussie. The figures there had been nearly as startling: of the 38 valley-born members, 18 (or 47.4 percent) were lefties. “And I’m not counting myself,” said the Newtonmore secretary, Sandy Russell, a switch-hitter who once held a right-handed handicap of 5 and a lefty of 7.

Nine summers later, the left-handedness of both memberships was holding up well. Of the 31 valley-born members at Kingussie, 11 (or 35.5 percent) were left-handed. At Newtonmore, I learned that 17 (or 41.5 percent) of the 41 members were lefty, ignoring an influx of four cack-handers.

How about the ladies? Kingussie secretary MacWilliam looked down the ledger and, with mounting frustration, noted names added to and scratched from the columns. “They are always chopping and changing, joining and resigning, these ladies,” he said. “But in the past we reckoned there were only about one in 12 lefties among the ladies in the whole of Badenoch.” That’s only 8.5 percent. “Ladies, you see, dunna play shinty, even as girls,”MacWilliam said. “Shinty is the native game of the Highlands. It is a bat-and-ball game, rather like field hockey, and it’s played by boys and men. Have a word with Jack Richmond, down at the Badenoch Hotel in Newtonmore. Jack knows more about shinty than anyone in the world.”

My inquiry was to take its last shadowy turn.

Newtonmore’s course, on flatter land, is perhaps less challenging than the one at Kingussie, covering 5,890 yards from the tiger tees for a par of 68. But it is attractive all the same, and in its wood clubhouse hangs a framed photograph of Bob Charles, king of the lefties. In it, he is smashing a low, galloping drive with one of those shinty sticks. Charles had paid a visit after the British Open last summer at St Andrews. “Ah,” said the New Zealander, “now I see how it’s done.”

The imperfect clue was soon expanded upon by Jack Richmond, MBE, in the nearby Badenoch Hotel. Richmond, who earned Member of the British Empire for his “services to shinty” in the 1982 Queen’s Birthday list, is the world authority on the native highland game.

“The left-handedness of our golfers obviously goes back to shinty which, properly, is called ‘camanachd’, which, in Gaelic, means ‘the game of the curved stick’,” Richmond said. “Since the shinty stick, the ‘caman’, is two-faced, there is no preference, left or right, in stick co-ordination. A shinty player is used to hitting the ball as often with the left as the right face of the stick, which, interestingly, is raked back to as much as a 5-wood in golf.”

Nothing in shinty, Richmond continued, forbids a player from taking a shoulder-high swipe at the ball. Result: a shinty swing often looks much like a golf swing.

Pondering his words that evening, I took the road from the Land of the Lefties, drove up through the Monadhliath Mountains towards Inverness and the night flight to London. Yes, indeed, the strange highlands game was plainly a root cause of left-handedness among the golfers of the District of Badenoch.

Yet one unsolved puzzle had now been replaced by another. What was I to make of the notion that camanachd might well be a forerunner of golf? The road swung left, and gazing back down into that mysterious valley, I could find no hint, no answer. Nightfall, like the very mists of antiquity, had settled in over the Land of the Lefties.

Did you know?

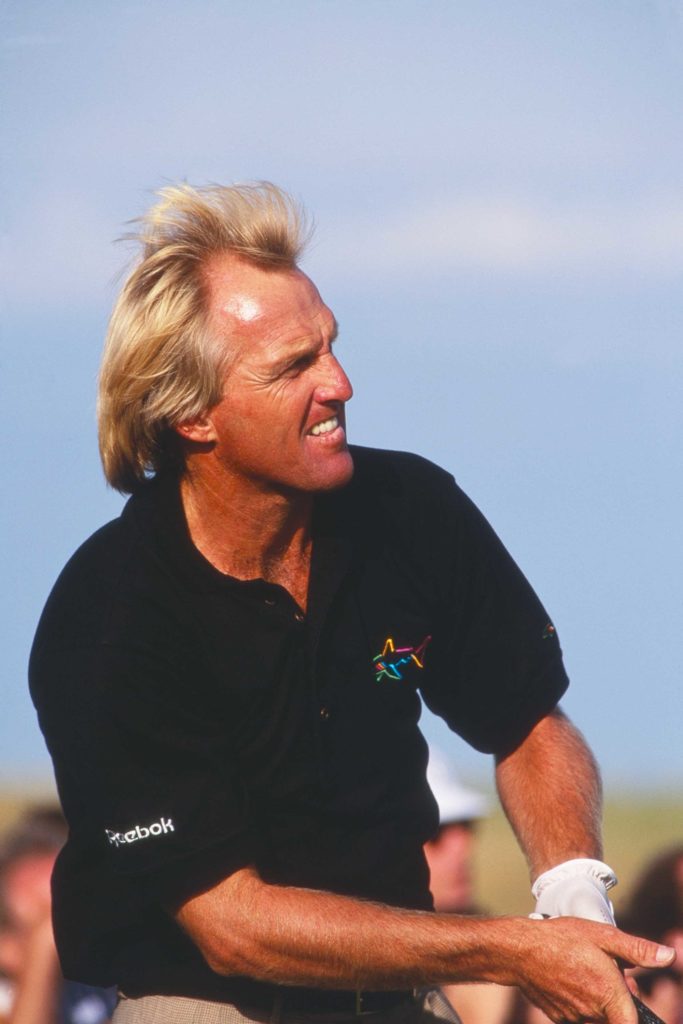

Of the four left-handed players who have won Majors – Bob Charles, Mike Weir, Phil Mickelson, and Bubba Watson – only Watson is a natural lefty. There’s also the even more surprising fact that six other natural lefties have won Majors, but all while playing right-handed: Johnny Miller, Greg Norman, Curtis Strange, Nick Price, David Graham and Byron Nelson.