Greg Norman on taming Royal St George’s, snaring two Open Championships (and almost a third), cloning claret jugs and what playing alongside Nick Faldo was really like.

Brought to you by the COBRA KING Putter Series

Greg Norman does not own a long and rich history with the Open Championship prior to his playing days. His first Open as a participant came in 1977 at Turnberry but his first memory of The Open is from a mere two years earlier when countryman Jack Newton parried away the charges of Jack Nicklaus and Johnny Miller before falling to Tom Watson in an 18-hole playoff.

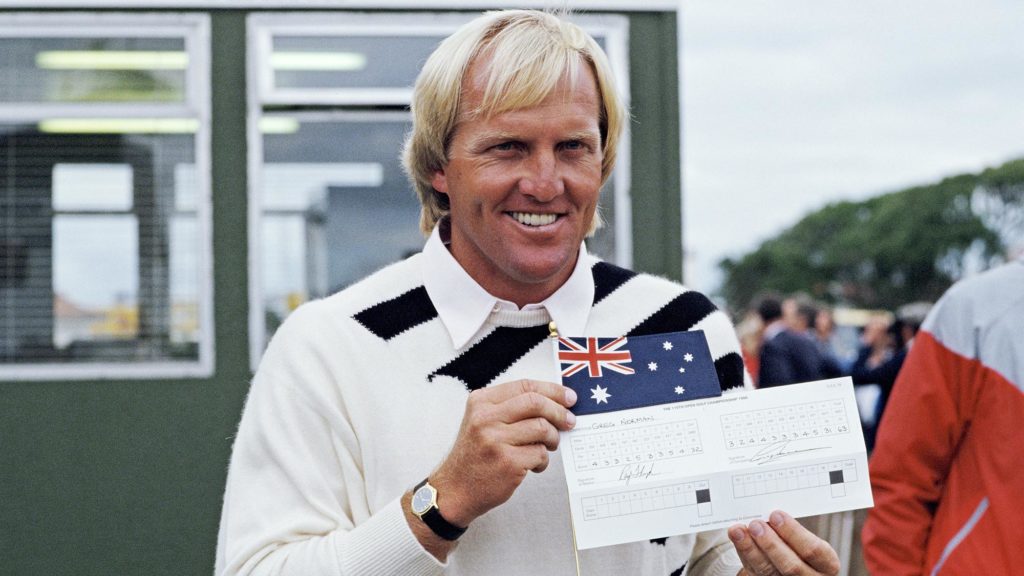

Norman played in 27 Open Championships between 1977 and 2009, winning twice, losing in a playoff another time and enjoying a spirited third-place finish at age 53 in his penultimate appearance. Among Australian golfers, his Open résumé is surpassed by only five-time Open champion Peter Thomson and the pair are part of an elite, four-member club – along with Kel Nagle and Ian Baker-Finch – as Aussie golfers to have claimed the claret jug.

Remarkably in the age of YouTube and instant digital access to the sporting past, Norman has never re-watched either of his Open triumphs. “I don’t go back over the past,” he says. “I’m the guy who’s: ‘What’s done is done and move on.’

“It’s incredible how athletes can recall certain feelings, certain shots, certain moments in time. That’s our training mechanism, that’s what makes us who we are. We have that ability to recall, but I don’t need to be refreshed.”

Yet the Great White Shark still has plenty to say about The Open, the rota of courses, his recollections and rivals, plus golf and life in general. Join us on this ride down Open Championship Lane. – Steve Keipert

On HIS FIRST OPEN EXPERIENCE

The 1975 Open at Carnoustie was a focal point in Australia at the time – the Open with Tom Watson, Jack Newton, Jack Nicklaus and Johnny Miller. It’s the one that came to the forefront because

the Australian media were covering it because of Jack Newton. I probably followed more the Masters than The Open at that time, because it seemed like the Masters got most of the attention, being the first Major of the year.

Then, two years later, I made my debut at Turnberry, where Jack Nicklaus and Tom had their Duel in the Sun. It was very unusual for Scottish weather to be delivering that type of temperature and playability. The golf course was wispy and fiery. In the end, two of the best players in the world collided at the right time. It was a matchplay situation, but to see the best of the best playing their best – I don’t care whether it’s on a pitch-n-putt course – that’s pretty impressive to see. From a player’s perspective, there’s nothing better than seeing the best bowler going against the best batsman, the best centre half forward going against the best centre half back. There’s nothing better than seeing the best sportsmen and women at each other at their peak.

I do remember that Open but I don’t remember how I played [Norman missed the third-round cut after scores of 78, 72 and 74. The R&A did away with third-round cuts after 1985]. It was more of the learning curve for me to step up to the plate. A lot of the golf I’d been playing leading up to that Open in ’77 was more parkland golf: practising at Royal Queensland, playing in Australia. Most of the golf courses I’d played in those days weren’t really linksy-type golf courses. When I got to Japan, the same thing. They’re more parkland-style golf courses. Then, I get to Europe and they’re all parkland golf courses. So I really didn’t get to feel what Scottish golf courses and links golf was all about. There was a transition period. But I came out of ’77 knowing I had to make some adjustments to my game when I went back to play The Open.

On dismantling Turnberry in ’86

I knew, when I got there for my practice rounds, that I was going to do well around Turnberry because it was the narrowest fairways we’d ever experienced at an Open Championship or any Major.

The rough was the most severe. There were a lot of complaints coming from the players saying they were going to break their wrists, hurt themselves and stuff like: “Get in there and cut it, cut it, cut it.” It was always wet because it was raining a lot of that heavy moisture, Scottish moisture. The rough was even harder, heavier and thicker.

I knew during Tuesday’s practice round with my caddie Pete Bender that I was going to do well because I was driving the ball so well. I was hitting these really long power fades. I’d aim down the left side of the fairway and just hit it. It was just beautiful control I had over my driver all week. It wasn’t like that just on the Friday or the Sunday, it was all week.

So, I knew my driver was going to be the ace up my sleeve. As it turned out, it was, because the rough intimidated other people. I wasn’t intimidated. I can’t remember what percentage of fairways I hit, but I bet it was high for the circumstances. There were fairways 19, 22 yards wide and that’s at the landing areas. It was extremely demanding.

I walked away from that disappointed too, because when I shot 63 in the second round under these very adverse conditions, I finished three-putt, three-putt for par, bogey. If I go one-putt, one-putt, I shoot 59. I was that close to doing it. I wasn’t thinking about that at the time, though. Somebody brought it up and mentioned it a little bit later.

That 63 would be in my top three rounds ever. It was my game plan and I stuck to my game plan of using my greatest asset, my driver. I was a really good driver of the golf ball and I took advantage of it.

Even with a five-shot lead, I didn’t let myself think, This is mine. Not until I hit the fairway at 18. You never think like that on the golf course. A lot of other people might think you think that way or want you to think that way, but a player never does. You’re in your moment, you’re in control, you’re playing one shot at a time, you’re trying to hole shots.

It wasn’t certain until I hit the fairway on 18. And that’s one of the great experiences that I’m disappointed that The Open stopped: allowing people to come onto the fairway at 18. From an Open champion’s perspective, that is one of the unique feelings in the world. When you are flooded by people and it spikes your senses in every way. People tapping you, yelling in your ear, cheering for you. Every sensory organ is elevated. Then, you’ve got to roll through it and get yourself back down because you still have to either chip or putt. It’s one of the most beautiful things that can happen in sport.

Will it ever come back? No, not in this environment today. For any sportsman or woman to experience that in the peak of the battle, it tells you the true passion and love that the Open Championship’s spectators have for Open Championships and for the players. They completely get it, they completely respect it, they completely understand how difficult the situations can be. We’re up there playing in 30-mile-an-hour winds and it’s pissing down rain. They’re there sitting in the bleachers in 30-mile-an-hour winds and pissing down rain. But they’re not complaining. How the hell can the players complain when they’re not?

On the stars aligning in ’93

I’ve obviously got good memories of Royal St George’s in 1993. It all started on the driving range on the Tuesday or Wednesday with Butch Harmon and my caddie, Tony Navarro. I was hitting the ball extremely well. Then, we made this conscious decision to get away from all the ‘white noise’ of the driving range. So we went over to the right-hand side of the range. Butch picked up a couple of bags of balls, Tony picked up the golf bag and off we walked. We found this really peaceful, quiet place behind the equipment trailers. We went over to really focus for about 45 minutes and were focusing on just one thing: keeping the club out in front of me and covering the ball, because it’s what you’ve got to do in links golf, or golf in general.

We had such a phenomenal practice session. Those 45 minutes, it was like, “Man, I was dialled in.” I was hitting balls within half a foot of where I wanted to hit them. It is crazy stuff when you get locked in like that. Everything felt great about my rotation and where the club was. I had shortened my swing just a little smidgen, but I had shortened my swing with a full shoulder turn so there weren’t any changes to that.

When we left the range, that’s when I really felt like I was going to be a big threat that week. I didn’t say it to anybody until after the fact, of course. Then, it played out that way. I double-bogeyed the first hole of the championship. I said to myself coming off the green, “You’ve got 71 holes to go. Don’t panic. You’re playing great. That was just a bad lie off… not a poor tee shot, but a kick left off the fairway mounds. I said, “Look, you’re playing great. Just look ahead on every shot.” And then, boom. It just went on from there.

When I look back on it, especially the Sunday round, it was a tough day of golf. When I drove to the golf course on Sunday, and I was walking to the driving range, that was the first time I looked at the leaderboard. And it was a stacked leaderboard of the who’s who of the top 10 or top 15 in the world. I said to myself, “You’ve got to go today, because you’ve got so many great players behind you. Somebody’s going to shoot low and come at you.”

Even though we knew the weather conditions were going to progressively get windier and windier as the day went on, I said to myself, “There’s too many great players for somebody not to shoot a good round.” That was my mindset. I thought, Keep the pedal to metal, suck up the go-go juice and just keep going. That was my approach as I went to the driving range, my approach when I went to the first tee and it didn’t matter who I was playing with, I was just focused ahead.

Was that closing 64 my greatest round? I wouldn’t say it’s the greatest but I’d put it in the top five, top seven, for sure. When you look back at it, and look at the scores from the other players, whether it’s Bernhard Langer, whether it’s Nick Faldo, whether it was Payne Stewart – there was a litany of players who put up numbers in the 60s there. So you knew, if you had a one-shot lead or were two shots behind, a 69 or a 70 was never going to do you any good. A great score, in the final round of The Open, yes, but it was never going to get you to the top of the heap.

It doesn’t happen all the time when you know you’ve got to go out and shoot low. You can’t force it. You’ve got to let it happen. At the same time, I think it was just one of those unique tournaments where there are so many great players doing the same thing as you wanted to do. Everybody was just sucked into this vortex of shooting low.

On being ‘in awe of myself’ after the ’93 Open

I didn’t really care how some of the journalists took that comment. It wasn’t a comment of arrogance; it was a comment of confidence. When you do feel you’re capable of doing things that other people can’t, that’s a great feeling to have in the world. It’s a reflection of your own confidence and your own ability to do something. No matter what comment a player makes, somebody’s going to misconstrue it to their beliefs, or they’re biased towards that individual. I don’t care whether you’re the president of the United States, a CEO of a company or an athlete.

Those things don’t affect me, but there was a bit of, “What are these people coming off at and saying the stuff that they’re saying instead of looking back and saying, ‘OK, what did he really mean and why?’” You’re asking me the question and I’m giving it to you.

If you go back and look at that round of 64 on Sunday, I would say 70 to 80 percent of my shots were hole-high. That’s total control of the trajectory and spin of the golf ball. Even today, as I sit here and watch some of these great players today, their lack of distance control is just mind-boggling. They’re hitting wedges from 150 yards and they’re 45 feet long, or short, or left, or right. It’s just mind-blowing. You go, “OK, different accepting standards.”

Every player tries to peak at the right time. Every player. That’s why we practise. When you’re in the lead and you’re ready to go, whether it’s The Open or whether it’s some tournament in the middle of outback Australia. If you’re one of the top players in the world, your expectations – along with everybody else’s expectations – are that you’ve got to win it. You’ve got to be close to winning it. You’ve got to contend in it. As you prepare to go to a golf tournament, you have to go in with that mindset, and preparation has everything to do with it.

To feel that locked in, people who don’t experience that level of control could never understand how simple it feels. That’s what it’s all about. That’s why we practise. That’s why we train our bodies. That’s why we train our minds. That’s why we have coaches. That’s why we get honed in the best way we possibly can and it’s very difficult. But it feels easy.

I’ll never forget a great example from Nigel Mansell, the Formula 1 racecar driver. I was with him at the British Grand Prix around the mid-’80s. I was sitting on the pit lane wall and he’s leading the grand prix. He’s whipping by and I’m talking to somebody beside me. He must have been doing 220, 230 down the stretch. He finishes the race. “Congratulations. Well done!” And he says, “Hey, what were you talking about on the pit lane wall with that guy?” And I’m going, “Oh my God.”

You think about it: he’s whipping by at 230 and everything must have slowed down in his mind. That’s why he’s so great at it. It slows down. You see everything. You feel everything. It’s like you’re in a totally different world. That’s no different than golf – it’s the same with us. Even though you play five-and-a-half hours for 18 holes, it feels like it’s half an hour. You feel like, “Can I just keep going?” It’s very, very difficult to explain.

On ‘making love to your fingers’

One of the things I recall driving to Royal St George’s that Sunday morning is how I was thinking about relaxation and breathing, which you normally do anyway. Grabbing the steering wheel of the car, I actually said to myself, “Make love to your fingers.” When I grabbed hold of the steering wheel, I was caressing it and I was feeling it. I had a lot of sensitivity in my fingertips. The feedback up my body was just really relaxed, instead of squeezing the steering wheel like a lot of people do.

You get to The Open and there are those little, tiny, narrow roads. You’ve got to allocate an hour when it can take five minutes. So I wanted to not get amped up in any way, shape or form. To this day, I still use that same messaging. I didn’t say it to anybody then, but I’ve used it probably a dozen times in my life since then, publicly and during clinics. You make love to your fingers when you grab hold of the golf club, right? You don’t squeeze the golf club. That’s where that saying started.

On playing Royal St George’s

I prepared really well with Tony Navarro that Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday in ’93. We had a strategy off the tee, for some of the lines off the tee and because of my length and how straight I could hit the golf ball. At Royal St George’s, there are a lot of fairly sharp doglegs. Tony and I, we both thought that because of my length, I could actually hit across the doglegs and get to the widest part of the fairway not the narrowest part. That’s what I did on a lot of the holes. When people were laying up, I was like, “See you later, I’m going over the corner.”

Royal St George’s is not one of my favourite golf courses. There’s a lesson in the fact that you can actually go to a golf course, develop a game plan on the golf course, that… I’m not saying it doesn’t suit my eye, but I didn’t really like the layout. It felt quirky to me. I played there in the late ’70s when the British PGA Championship was there. Even then, I thought, This is not my golf course.

You have to figure out: are there circumstances where you are going to feel comfortable, in any situation? They’re different when you get up there and you make your first speech in front of 10,000 people. How do you make yourself relaxed, comfortable and be able to deliver, like you’re having a fireside chat? It’s no different going to Royal St George’s knowing I didn’t like the layout. I had to figure it out, figure out the best way to play it with my style of golf, which Tony and I did.

Where does the course sit within the Open rota? I’m not going to answer that in PC fashion; I would put it on the low end. It’s a very quirky golf course. There are a lot of different angles. It’s like a bowl of cooked spaghetti – it’s all over the place. It’s very hard when you play Royal St George’s without it being in The Open, when there’s no bleachers and TV towers. It’s very difficult to figure out where the centrelines on some of the fairways are. You have to play from knowledge and experience. You can’t just walk right up there, even if you have a local caddie that’s been there for 50 years and he tells you to “hit it over the sand dune, there’s a bunker over there, this is over there and it’s out-of-bounds here”, because you don’t see it. Sometimes it’s very difficult just to go and fire away.

It’s one of those golf courses where you need to do a lot of repetitions around it. You need to know it. And the weather changes there dramatically, from the wind out of the north-east, to the wind out of the south-east, to the wind out of the south. That whole course changes with a 10 or 12-degree shift in wind.

On the vagaries of sport

Could I have imagined that Open, at age 38, would wind up being my last Major title? No, of course not. Not at all. You don’t even think like that at the time because you’re going through life. Part of sitting back and reflecting on life, you can reflect back on the incidences, the situations, or what other players have done. That’s sport, and anything can happen in sport.

You think about it in cricket, soccer or swimming in the Olympics. You train for four years and you miss your turn by two one-hundredths of a second and you finish third. You think, OK, what did I do wrong there?

It’s sport. You do the best you possibly can in your training and you execute. You have no control over your opponent or your opposing team. When you look back on it, you see moments in time when you could have done better and you see moments in time when somebody else was just way better than you at that given time.

On celebrating Open victories

They were not wild nights after either Open. In ’93, by the time everything wound down – from media, the R&A, things you’ve got to do with the volunteers – it’s hours and hours and hours going by. I just went to the plane, got on and flew home with my family and friends. That was it.

Of course, you have a wine or two. You chill out, but most of the time you’re just tired. You’re coming off a big, hard, focused week, plus the intensity on and off the golf course.

In ’86 it was a little bit different, because there was a Concorde chartered flight that we flew over on and the Concorde was taking us back. Coincidentally, my good friend,

Captain John Cook, was bringing the Concorde in to land at Prestwick Airport. All the festivities were over and he committed a bit of an aviation no-no. He came in low over Ailsa Craig, knowing that all of us were standing down there with the trophy. He came straight up

the 18th hole at low level and just put it on its tail with the afterburners and

just launched it into the atmosphere. That was a cool, cool experience.

He landed. We all got on and I put the trophy up in the cockpit for him and his crew because he was a golf fanatic. I played quite a few rounds of golf with John. In that moment, that had nothing to do with me. That was just my friend who was so excited for me. It was a pretty cool experience.

Nobody knew about it, either. We just saw it coming because you could hear it coming. They’re a very big aircraft. Nobody knew what was going to happen. We just said, “OK, here it comes.” All of a sudden, he just dropped it down a little bit. It shook the entire hotel.

On trophy tales

In ’86, you were allowed to have a replica claret jug made but to only one-third of the size. I did that for my parents. Then I went to the jeweller who makes the replica. I knew who they were: Garrard, in London. We came to an agreement to replicate full-size. I might have been the first person to have a full-size replica; I’m not too sure.

The R&A found out afterwards and I think that’s when they realised, “Hey, no harm, no foul.” I paid for it. It cost a lot of money to get it done. You want to have a full-size replica. The only thing I didn’t do, out of respect for them, was put all the names on there. So, there are no names on the band. It’s just the trophy on the platform. I talked to them about it and I didn’t want to put them in a position where my trophy was stolen and wound up on the black market. That’s why I didn’t put the names on the trophies, even though the body of the claret jug was exactly the same as the original. I respected it to a degree but, personally, I wanted to have a full-size replica and so I did it. I ended up doing the same thing in ’93.

Of course, there are a lot of stories. In ’86 when I took it down to Australia, it was in a wooden crate with a very small handle. It was very awkward to carry, because it’s extremely heavy and you could only carry it with three fingers. I just enjoyed it on the Qantas flight going to Australia, because you had to hand-carry it, you couldn’t check it. People enjoyed it, the crew enjoyed it. Breaking it out on board, it’s amazing the joy that comes out of people’s faces when they actually get to hold the claret jug, because it’s the sexiest trophy in any sport, as far as I’m concerned. When people actually get to hold it, they go, “Oh man, the history of this! It’s more than 100 years old.”

Even the trophy the players keep for the year is an old one, but not as old as the original. You think, Wow, the history. What’s happened with this jug? Whose lips have been on it? Who’s kissed it? Who’s hugged it?

That’s the great thing about The Open – it is the people’s trophy. It is the true Open’s trophy. To get the chance for a year to take it around the world and let people experience it, feel it, touch it, understand it and take photographs with it, that’s one of the coolest things you can do with that trophy.

On contending again at age 53

Technology and certain golf courses were always going to allow a 50-something-year-old to win a Major, as Phil Mickelson proved at this year’s PGA Championship. It’s just a testament to the evolution of golf, the evolution of the golf swing and the body. I had my opportunity at the 2008 Open at Royal Birkdale and so did Tom Watson at Turnberry a year later.

I was 53 at the time, but I’m a very physically fit guy – I’ve looked after my body. So my 53 is a lot of people’s 43, maybe even a 40 in my situation because I hadn’t lost much distance. I still had power and flexibility. That’s a testament to what you do off the golf course, not what you do on the golf course.

Even today, when I go out and play – I shot my age the other day at 66 – I’ll ask, “OK, why is this?” It’s obviously a combination of technology with equipment, whether it’s the golf ball, the golf club, shafts – all those things.

I was cheering so hard for Tom. I did it twice in my life – pulled really hard for other people. One was for Tom Watson at that ’09 Open. The other one was Curtis Strange to shoot 59 around St Andrews when I was playing with him at a Dunhill Cup.

Conditions were really difficult at the ’08 Open. Equipment and physical fitness definitely helps, but that week was also about feel and trust. Every year, for at least a week before The Open, I went to Skibo Castle where I’m a member. I used to do my quiet practice there, getting ready for links golf by playing Royal Dornoch and Skibo, just practising on their golf courses. They’d let me go to a certain hole and practise my drivers, practise long irons. That was just a wonderful haven for me.

That week at Skibo, I was practising and I was hitting the ball terribly. The weather was terrible. I looked at the long-range forecast and it was going to be the same down at Birkdale. I actually nearly withdrew from The Open because I thought, Oh gosh, I’m playing so bad. I really don’t want to take a place away from a young kid and give them a chance at doing it.

On the Sunday I was due to leave, I almost picked up the phone and said, “I’m going to withdraw. I’m going to head back to America.” When I looked at the long-range forecast, that afternoon at Skibo I went out and played without a yardage book. That turned me around because I started playing by feel.

It was an extremely windy day that day, about 30 miles per hour. The golf course was playing tough. I played without a yardage book, played on my own, played by feel. Lo and behold, everything just came flooding back to me. I thought, OK, let’s just go down, the conditions are going to be the same up until Thursday. Let alone staying the same all week.

When I went down to Birkdale and played my practice rounds, I was hitting 5-irons from 90 yards, 110 yards. I was doing these little bump-’n-runs and everybody was looking at me like, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m just feeling my way around the golf course.” Then, come Thursday, I felt really good because I was playing it by pure feel.

That week I had veteran caddie Linn Strickler, known as “The Growler”, caddieing for me. He was one of the true characters of the caddie world and a good one. I had known him from the tour days and he was a friend of Tony Navarro. His greatest input was his professionalism. He had been there before with other players so he was not intimidated at all by the situation. And he let me play my ‘feel’ game when I needed it that week. Although not every shot I played by feel; there were shots that we did need our yardage. But that’s how the whole week evolved. I just played from pure experience.

On his Open near-misses

I wound up finishing equal third in 2008, and I also consider the playoff loss at the 1989 Open at Royal Troon to be among my closest calls for a third Open title. Yet right up there is Carnoustie in 1999. I was very disappointed I didn’t win that year.

I’ll never forget this: I took a triple on the 17th hole. I’d hit a beautiful drive down 17 and the ball bounced just a little bit right in rough that’s so severe. I just missed the second cut and was in the primary cut and I was just a few inches into the heavy rough and I couldn’t see my golf ball.

That year’s the one that gets me the most, because I love Carnoustie. It’s a great player’s golf course, because it’s a true challenge from tee to green. I was playing it really well. I’ll never forget that hole. I took a triple-bogey and went, “Oh my gosh, OK.” You look to the skies and you say, “Why? Why? Why?” It was the same thing at Troon against Mark Calcavecchia and Wayne Grady. My ball landing on a downslope on the 18th fairway on the last playoff hole and reaching a bunker I never even had in my yardage book. You go, “OK, c’est la vie. That’s golf.” And that’s links golf.

You think, If it landed 10 feet shorter, it would have hit the upslope and it would have been fine. Then, I’m on the downslope in a bunker because it just trickles in and I’ve got an almost impossible shot. Of course you can think back on those things and say, “Why? Why did the golfing gods decide to strike down and do that?” Instead you look at it and say, “Hey, it’s just sport. That’s what happens in sport.”

To me, it’s not life threatening, right? It’s just not something that affects me mentally. I just accept those realities of life and move on. It’s just like Larry Mize’s chip at the 1987 Masters. You go, “OK, what would have happened if that hadn’t gone in?” What has happened to Larry Mize since he won that green jacket? What’s happened to me since I didn’t win that green jacket? You look at all that stuff. If you want to go back and be psychoanalytical about it, you can go whichever direction you want to go.

On playing alongside Nick Faldo

I vividly remember playing Faldo at St Andrews at the 1990 Open, both of us wanting to win at St Andrews. Nick and I have never been the best of buddies. I never really enjoyed playing golf with Nick because his approach to the game is different to mine. I knew it was going to be a hard day that Saturday, well, that week, actually. I was playing well; I shot two 66s the first two rounds. Nick shot the same two-round score.

When I look at some of the battles I’ve had with Faldo over time, they’ve been interesting. St Andrews, I’ll remember that one because it was an interesting day. When I play golf, I enjoy playing the game of golf with my playing partners. When we play and you hit a great shot, I’ll say, “Great shot,” or, “Great birdie,” or, “Great chip,” or, “Let’s go have some fun today.”

I’ll never forget 1981 when I played my first Masters. On Saturday, I’m playing with Jack Nicklaus. We both drove it off the first tee and we both drove it well. Jack comes up to me about 40 yards off the front of the first tee when all the cameras were off – Jack was a master of that. He came up and put his hand on my right shoulder and said, “I hope you’re as nervous as I am. Let’s go have a great day.”

Now, I think about that statement and I go, He’s the best player in the history of the game of golf. He’s as nervous as s–t. I’m nervous, of course. I’m excited about playing with him as well as Augusta National for my first ever Masters. He sensed that and had the purity about him to bring you down, just, “OK, let’s go have a fun day.” I loved that day with him. Ever since then, it elevated Jack in my standings.

Going back to Nick, he would never say, “Good shot. Good putt.” Wouldn’t say a word to you. I’m thinking, OK, I will still say it to him. “Hey Nick, great putt.” I would never lower myself to that standard. I never understood why. It’s a game of golf; you respect whom you’re playing against and you respect the game. That was one of the things with Nick that bothered me and he was the only one who was like that.

Curtis Strange was probably one of the toughest competitors, but he and I were good mates. We would go fishing and stuff like that. There was always a little bit of banter but we focused on our game. With Nick, you would never get a word out of him from the first tee to when you were in the scorers hut.

On bridging the generations between Peter Thomson and today

When I first came on the scene, everybody talked about Peter’s five Open Championships. He and I talked about the transition from the small to the big ball and what Peter did with the small ball. It’s not an easy ball to play golf with. Sure, it goes further and goes through the wind easier but it also sits down in any imperfection on the fairways. His ball-striking ability and those guys in those days, using the small ball, was pretty damn impressive with the equipment they had.

I would go out on a limb in saying that there’s a lot of players playing today, with the equipment they’re playing today, that probably couldn’t handle the small ball as well as they do the big ball. The 1.62-inch ball was a very interesting one to practise with. I used to practise with the 1.62 along with the 1.68, just to learn how to strike the ball clean. Peter was a very crisp striker. I loved his golf swing; it was a very simple motion.

We talked about a lot when I first came on the scene in ’76, ’77. I’ll never forget walking around with Peter at Victoria Golf Club. I was playing and Peter walked around with me to watch me play. I can’t remember the exact conversation but I do remember him walking the first four to six holes with me, because I was the new kid on the block. He was very aware of his role of being the patriarch in a lot of ways, even in his journalistic skills and his political skills. He was very astute about his position.

I think I got a lot of those teachings from him just by observing him. His approach to life is different than mine, of course. His teachings of life and your roles and responsibilities to the game of golf, which he obviously drew through his victories at the Open Championship. Well, he handed that baton down to me in a very simple, responsible fashion and I accepted it.

Peter was very, very, succinct in his delivery and his message. Tom Watson was exactly the same way. Tom Watson was a fierce protector of the game of golf. Fierce. No different than what Peter Thomson was. Raymond Floyd was the same way. Jack Nicklaus not so much. Jack was a little bit gentler in the way he would deliver the message.

Definitely with Peter, if you were saying the wrong things for the wrong reasons, you would get a message from him for sure. That’s wonderful to be able to do. Today, you couldn’t do that.

In that situation it’s up to the next generation if they want to come in. I was the type of guy who never had a problem asking Peter a question or asking a prime minister a question, or a president a question, or a CEO, or seeking help. That’s how you broaden your horizons. That’s how you learn a lot more and you learn faster – by taking other people’s experiences, positive and negative, and putting them into your recipe for life.

On how the Old Course influenced his design career

The evolution of my course-design career didn’t change my appreciation of the Old Course at St Andrews, it magnified my appreciation for it. Because the art of designing a golf course that survived the test of time is pretty impressive. I try to instill that within my team. When I think back on all the golf courses I’ve built and how I look at Royal Melbourne, how I look at Kingston Heath, at Yarra Yarra, at Huntingdale before it was changed (I wish they had never changed Huntingdale). When I look back at those golf courses, the art of building a golf course like that with a horse and plough is pretty impressive. Using Mother Nature’s topography as it is and just putting the green complexes in the most advantageous place, without having to move a lot of dirt. St Andrews is like that. When you see all the undulations and the ups and downs and the little tiny pot bunkers 180 yards off the tee and you think, Well, why would they even put that there? The next day, the wind is blowing 40 and you go, “Oh s–t, there’s that little pot bunker!” And now you’ve got to worry about it.

St Andrews has an effect on how I design golf courses today because you can play the golf course backwards. Every golf course where I walk on a virgin site and during heavy construction, I always look back and say, “Can you play this hole the opposite direction?” Taking into consideration the sun, the wind and the topography. Then, if you get it right in one direction, you’ve got it right in the other direction.

I’ve seen a lot of golf courses designed with the reverse camber, where it actually plays better in the opposite direction, and plays horrible in the way the golf course was built. I got that from St Andrews.

It’s very easy, and very few people would stand on the green that you just played, look back and say, “OK, I can’t see any bunkers. I know they’re there, but if those bunkers were looking at me the other way when I’m looking back there, how good would that look?” Instead you go, “Those long views are great. The topography looks good. Look at that tree there or that rock there or this there.” It’s all framed going back the other way.

I’ve experienced St Andrews where you’re on the wrong side of the draw. You’re playing into the wind going out and the wind switches and you’re playing into the wind coming back. It’s a five-shot swing. It’s just brutal that way and that happens. It’s the luck of the draw, as they say. I’ve experienced that. I’ve experienced it the other way too. Where you’re downwind, downwind.

Every time I got a tee-time at St Andrews, I looked at the tide chart.

I could see, “OK, so the weather’s going to do this…” So now you’ve got to be prepared. Now, you’re putting more rain gear in the bag, you put gloves in. And you know there’s a chance you’ll carry a 50-pound bag and not a 40-pound bag.

On which of The Open courses is toughest

It depends on the weather. If they’re all played under benign conditions, they’re more gettable. The links golf courses are designed for the Scottish and the English weather. You’ve got to learn how to play it on the ground. The golf layout I love the most is St Andrews because you can play that golf course in a multitude of different ways, including backwards. The Open venue I love to play the most, because it challenges you from a shot-making ability and for ball-flighting, would be St Andrews. Second on my list would be Muirfield. Third would be Turnberry. Fourth would be a tie between Carnoustie and Royal Troon.

On tweaking equipment for The Open

I made all my golf clubs, basically. As in, I stripped them down, altered the bounces of my own sand wedges, knowing what golf courses I was going to. I perfected what I did to the heel of the club – to be able to lay back the leading edge. When you go to Open golf courses, you don’t want to have a whole lot of bounce. The sand in the bunkers is tough. You’ve got to find that fine line about no bounce on the hard areas – where you want to pitch around the greens – to having a little bit of bounce for the type of sand they have there, which can sometimes be pretty powdery even though it’s dark-coloured. You had to be really careful with that combination. By cutting back the heel of my sand wedge, I could lay it way open and take a 54-degree and make it play like a 60 and still have the leading edge on the ground. That was the stuff I always like to do myself.

My driver was my driver. I never changed that. With the scoring clubs, to me, the art of playing really great golf is hitting the ball hole-high all time. If you’ve got your equipment dialled in, you can do that.

On his longevity at the top

I was driven. I was self-driven. I was motivated. I was self-motivated. A lot of people when I first came onto the scene wrote some not-so-friendly things about me and I couldn’t understand it. I played golf not to prove them wrong, I played golf to prove myself right.

I had Charlie Earp as my mentor and coach but he never travelled with me; I didn’t have him close in the circle. I had to make all the decisions I made on my own. He taught me how to be compartmentalised with some of those decisions and the things you do in life. My primary focus was to be the best I could be on the golf course. That’s all it was. My failures were my successes in a lot of ways.

I have a very strong mind and heart to be able to take some of the knocks I took, and I took them on the chin because it’s just sport. When I look back on my life, some of the rhetoric that was said about me is really disappointed, because people judge me without knowing me. You should never judge anybody without knowing the human being and what they are really like behind the scenes. Just because I had blond hair, could hit the ball a long way and could play golf better than most, don’t pre-judge me.

That’s probably one of the reasons why, quite honestly, I don’t go back and read history, because a lot of it’s predicated on judgmental comments. But I’m not saying it’s all that way – there’s a great supportive structure around me with the media, to a degree, because I always treated the media as: you have your profession, I have my profession. If I succeed in mine, you succeed in yours. If I fail in mine, you still have to do your job. I don’t think I ever rejected a press conference. That was part of that role and those responsibilities Peter Thomson instilled in me: you’ve got to face the music, good and bad.

I’ve always respected other people’s professions. Even though you walk into that media room in the ’80s and early ’90s, you know there’s a percentage of people not believing a word you say, taking a word and misconstruing it. Or, an editor puts it into a headline and that headline has nothing to do with the article, and boom. That’s how it is. You think, OK, why do I need to go back and regurgitate all that stuff?

On never truly retiring from golf

Not playing another Open after 2009 was just a decision that evolved. It had nothing to do with Birkdale the year before. It had everything to do with: I had other things I was enjoying doing in life. I’m not a ceremonial golfer. I personally do not like to see that – players going out there shooting 80s and taking a spot away from a kid who could be out there shooting 68 for his first time. I don’t believe in that. I’d rather give that opportunity to another person and hopefully it’s a younger person to learn how to play Open golf.

It was a decision I just thought was fair for the game, fair for me and fair for The Open, and it was easy. I’ve never really retired from the game of golf, I just partly walked off into the sunset. It’s not like I want my final round of The Open and to stand on the Swilcan Bridge and say goodbye to everybody. Or to go to Australia and play any one of the golf courses I’ve played and say, “This is my last round of golf, I’m never playing golf again.” That’s not true. When you retire from golf, you actually retire from golf. You never pick up a golf club again. I was never going to be that way.

I’ve got people asking me if I’ll go and play St Andrews next year. It’s one of my favourite golf courses in the world and I might look at my schedule and think, That would be a pretty cool thing to do. Am I really going to go there and play? No. I don’t want to get on the first tee and be that ceremonial golfer. I don’t want to do that. It’s just not in my DNA. So I just quietly say no to everybody.

Greg Norman’s record at the Open Championship

| Year | Position | Scores | Prizemoney |

| 1977 | T-59 | 78-72-74—224 | €0 |

| 1978 | T-29 | 72-73-74-72—291 | €738 |

| 1979 | T-10 | 73-71-72-76—292 | €5,600 |

| 1980 | 85th | 74-74-76—224 | €490 |

| 1981 | T-31 | 72-75-72-72—291 | €1,225 |

| 1982 | T-27 | 73-75-76-72—296 | €2,240 |

| 1983 | T-19 | 75-71-70-67—283 | €4,140 |

| 1984 | T-6 | 67-74-74-67—282 | €22,946 |

| 1985 | T-16 | 71-72-71-73—287 | €11,060 |

| 1986 | 1st | 74-63-74-69—280 | €98,000 |

| 1987 | T-35 | 71-71-74-75—291 | €4,900 |

| 1988 | DNP | ||

| 1989 | T-2 | 69-70-72-64—275 | €77,000 |

| 1990 | T-6 | 66-66-76-69—277 | €39,900 |

| 1991 | T-9 | 74-68-71-66—279 | €31,967 |

| 1992 | 18th | 71-72-70-68—281 | €18,480 |

| 1993 | 1st | 66-68-69-64—267 | €140,000 |

| 1994 | T-11 | 71-67-69-69—276 | €27,067 |

| 1995 | T-15 | 71-74-72-70—287 | €25,480 |

| 1996 | T-7 | 71-68-71-67—277 | €49,000 |

| 1997 | T-36 | 69-73-70-75—287 | €11,130 |

| 1998 | DNP | ||

| 1999 | 6th | 76-70-75-72—293 | €98,000 |

| 2000 | DNP | ||

| 2001 | DNP | ||

| 2002 | T-18 | 71-72-71-68—282 | €64,166 |

| 2003 | T-18 | 69-79-74-68—290 | €60,648 |

| 2004 | MC | 73-76—149 | €3,370 |

| 2005 | T-60 | 72-71-70-76—289 | €14,547 |

| 2006 | DNP | ||

| 2007 | DNP | ||

| 2008 | T-3 | 70-70-72-77—289 | €319,112 |

| 2009 | MC | 77-75—152 | €2,426 |

This is an edited extract from the upcoming book, Aussies at The Open, by Steve Keipert and Tony Webeck, © 2022, CMMA Digital & Print, which traces the fortunes of every Australian golfer to ever play in The Open ahead of the 150th Open Championship at St Andrews next July. Register your interest for buying a copy by visiting australiangolfdigest.com.au/aussiesattheopen

Featured Image by Omar Cruz