Most golfers have selective memories. Ask us to recount our best shots, and we can tell you the club we hit, where we hit it, and whatever it was we just had for lunch. It’s everything else that tends to be a blur. The implication of needing just one great shot to “bring you back” is that you’re choosing to repress all the mediocre shots that came before and after.

Even the best in the world can filter the game this way. Consider the eventful September that Billy Horschel had in 2014, when he won the BMW Championship and the Tour Championship, which also meant the FedEx Cup and its $US10 million bonus. A lucrative hot streak made all the more impressive considering what had immediately preceded: the week before the BMW, at the Deutsche Bank Championship, Horschel hit one of the worst shots imaginable under pressure when he chunked a 6-iron into a hazard on the final hole and lost by two.

When it came time to make sense of what happened, Horschel’s strategy was to dismiss it as mostly rotten luck. He knew he played well, had put himself in contention, and says the sidehill lie was tricky enough that he caught more turf than he anticipated. It happens in golf, and he didn’t see the point in dwelling. That he won twice in the next two weeks suggests he was right. “Just a really bad swing at the wrong time,” Horschel says.

Fast-forward to November 2016, though, and Horschel committed another tournament-ending blunder when he missed a two-foot putt to remain in a playoff in the RSM Classic. This time there was no redemptive follow-up, but here, too, Horschel says he profited from the experience. Revisiting the sequence, he recognised he had rushed through his routine, and that a weak left hand on the putter kept the clubface open at impact. It was a crucial mistake, but at least he understood why.

“It’s a tough way to learn something, but I learned it,” he said days later.

Horschel’s two high-profile tournament losses represent distinct case studies of how people handle losing effectively – one where they graze lightly over their worst moments, another in which they look more carefully. More than most golfers, Horschel has embraced how to benefit from losing. I wrote a book about this concept, Win At Losing: How Our Biggest Setbacks Can Lead To Our Greatest Gains, which explores the various ways losing and failure are often the most fertile opportunities for growth. In everything from sports to business to politics, my argument is that within our biggest mistakes are the lessons for how to be better.

Ever play decently after hitting the ball terribly at the range?

There might be a connection

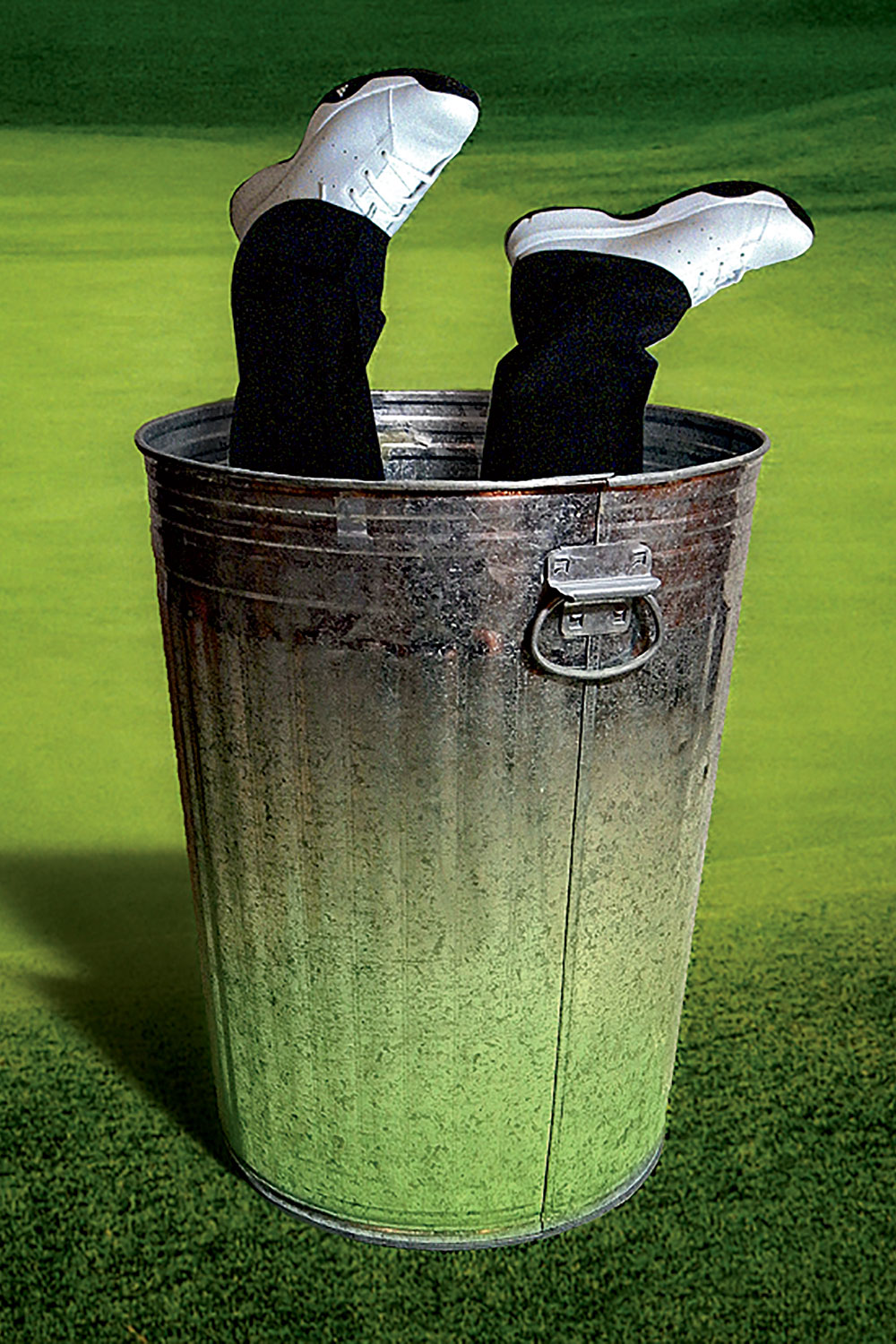

On an abstract level, it’s a principle most can embrace, but where golf presents a unique counter is when considering our often-fragile psyches. The last thing any of us wants standing over the ball is a catalogue of our worst swings swirling in our heads.

Dr Bob Rotella argues that rather than contemplate all the ways a golf shot can go wrong, we need to channel our energy to what we want to see happen. “No one wins if they don’t believe it,” says Rotella, whose book, Golf Is A Game Of Confidence, speaks to his theory. “People will say skill is most important, but I know plenty of guys on the range who have skill and who don’t believe, and I know guys who don’t have as much skill but who believe. I know who I’m taking on tournament day.”

Here’s an often-quoted maxim from golf’s greatest champion, Jack Nicklaus: “Confidence is the most important single factor in this game.” But even Nicklaus says confidence has minimal value if it means suppressing the most valuable information.

Here’s an often-quoted maxim from golf’s greatest champion, Jack Nicklaus: “Confidence is the most important single factor in this game.” But even Nicklaus says confidence has minimal value if it means suppressing the most valuable information.

“Somebody saying you’ve got to always be positive and eliminate all the other things in your mind and then hit a shot sounds good, but it isn’t an ideal approach,” Nicklaus says. “The realm of hitting a golf shot to me is, to be able to stand up knowing the shot I want to hit and knowing the problems I’ve had so I can then be positive about playing that shot. I want to know all the factors. I want to know all the negatives so I can create a positive.”

What Nicklaus describes is what Dr Fran Pirozzolo, a sport psychologist and mental-skills coach, calls “healthy self-doubt”, in which we’re aware of our limitations and can construct a game plan to counter them. In the same way Horschel learned the hard way what happens when he rushes his putting routine, there is value in knowing what precisely holds us back.

“Confidence is a garbage term in that it induces illusions of competence,” Pirozzolo says. “What you really need is a passion to work hard to get the best answers about why things happen the way they do.”

Even at the game’s highest rung, this is a tough place to go. Of 200 players or so on tour, Horschel estimates maybe only 30 are willing to spend time truly digging into the deficiencies that cost them. “Everyone else is scared to look in the mirror,” he says. “They shield themselves from it. That’s what makes guys like Rory and Spieth so great. They never shy away from their mistakes.”

Whether you’re chunking a 6-iron with $1 million on the line or blowing a 3-up lead in a $5 nassau, golf’s relationship with failure is complicated. There’s the belief we needn’t breathe life into our mistakes for fear they will fester. On the other hand, it might be better to tackle problems surgically and strategically. When US PGA Tour winner Peter Malnati was in college, he had a teammate who refused to attribute the bad shots he hit to anything within his control. “It was always the grooves on his wedges, or something like that,” Malnati says. “I wish I could turn my brain off in the same way. But that’s not how I’m wired.”

Malnati need not worry, according to Pirozzolo, who argues those bad shots are vital to improvement. After decades working with tour players like Bernhard Langer and Major League Baseball teams like the New York Yankees, Pirozzolo is a proponent of a process he describes as “not this, but that”, in which the better way to groove the feel of a proper athletic movement is to introduce the various feels of bad ones. It’s the difference between confidence, which he considers a shallow trait, and competence, a mastery that can best be achieved through a process of elimination. A simple example: in practising a five-foot putt, you hit the ball three feet past the hole. What some might see as the ingraining of a bad habit, Pirozzolo sees as training the brain to understand the difference. “You failed the first time,” he says, “but it helped all future attempts.”

Confidence is a garbage term in that it induces illusions of competence

Working through a specific problem is far more effective than a practice session in which a golfer seems to be striking the ball perfectly, Pirozzolo says. It might explain why we inexplicably struggle after warm-up sessions in which everything seemed to be clicking. The 2006 US Open champion, Geoff Ogilvy, recognises the same dynamic.

“Certainly too much confidence, or overconfidence, leads to lazy shots. You just assume you’re going to play well all the time,” Ogilvy says. “There are tonnes of stories of guys leading up to the Masters, and they can’t miss a shot, and their families come in, and all of a sudden they shoot five-over on the front nine. It creates a lazy head space because you’re just sure good things are going to happen.”

The inverse scenario of the overconfident player stumbling in competition is the struggling player who ends up thriving, and even winning. Ever play decently after hitting the ball terribly at the range? There might be a connection. In the 2009 WGC–Accenture Match Play Championship, Ogilvy won his early round matches but knew he was lucky to do so, often blocking shots to the right by getting his hands stuck behind his hips at impact. Far from confident, Ogilvy was forced to identify a flaw he might have otherwise neglected. After working through a series of drills on the range, he corrected the problem and ended up beating Paul Casey in the final for his second World Golf Championship.

The inverse scenario of the overconfident player stumbling in competition is the struggling player who ends up thriving, and even winning. Ever play decently after hitting the ball terribly at the range? There might be a connection. In the 2009 WGC–Accenture Match Play Championship, Ogilvy won his early round matches but knew he was lucky to do so, often blocking shots to the right by getting his hands stuck behind his hips at impact. Far from confident, Ogilvy was forced to identify a flaw he might have otherwise neglected. After working through a series of drills on the range, he corrected the problem and ended up beating Paul Casey in the final for his second World Golf Championship.

“On Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, I couldn’t play at all, and then Saturday and Sunday was the best I ever played,” Ogilvy says. “It all came out of complete desperation and not much sleep.”

The disparate ways we approach our mistakes in golf is perhaps best encapsulated by the Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck, who famously divided our mindsets into two categories:

▶ A “fixed” mind-set describes people who seek validation of their abilities.

▶ A “growth” mind-set describes those who believe their skills can be cultivated through effort.

Dweck’s most celebrated experiment was issuing a fairly easy exam to a group of fifth-graders. When the kids fared well on the exam, half were praised for their intelligence, the other half for working hard on their answers. In a subsequent test, the two groups began to reflect fixed and growth-mindset tendencies. The “smart” kids grew frustrated when they no longer seemed as smart. The “effort” kids embraced the challenge of the test.

In competitive golf, the test always gets more difficult. A growth mindset embraces the idea that the game is one of perpetual improvement, with failure a vital ingredient. It explains how Horschel was able to approach each of his two tournament gaffes constructively rather than see them as some larger commentary on his worth as a golfer. Or why Jordan Spieth says it took his loss in the 2014 Masters to fuel his green-jacket win the next year – and why there’s reason to believe he has grown from his collapse there in 2016.

Meanwhile, fixed mindset tendencies are evidenced by the “lazy head space” of overconfident players who just feel like they’re supposed to play well. Consider one of Pirozzolo’s clients, Cameron Smith, the promising Queenslander who teamed with Jonas Blixt to win at New Orleans in April. Smith has already been tabbed as a future superstar. Among the psychologist’s messages? Don’t believe the hype.

“I tell [Smith], ‘You’re going to be hearing how great you are, and you need to know that’s not a good way to proceed,’” Pirozzolo says. “The reason he’s gotten to where he is is because he’s worked. A lot of what we preach among younger players is that their future depends on how firmly they can grasp the concept of this growth or learning mindset.”

Even more than with other sports, a growth-mindset approach to golf is vital because it allows for the stumbles that are such an inherent part of the game. Just do the maths. No one wins every time, and even those who display the high-level “competence” that Pirozzolo stresses do so within the larger context of missed fairways and putts.

“I think it’s important to understand that nobody is consistent at this game – nobody,” says instructor Martin Hall, ranked eighth on Golf Digest’s list of America’s Best Teachers. “You just have a range. You have your best and your worst, and if you’ve improved your game, you’ve just moved your bell curve.”

Hall, too, believes the only avenue to such improvement is by dissecting what isn’t working. He advises his students to write down in blue and red ink their swing thoughts over a given round – blue for those that helped, red for the ones that were problematic. For instance, Hall says the idea of swinging his arms down from the top has never worked for him, so he knows to steer clear. Like Billy Horschel missing a two-foot putt, the fact that he discovered it the hard way is still preferable to not knowing at all. “I don’t think negative is necessarily bad,” Hall says. “Negative is what can help eliminate a lot of problems for you.”

In addition to athletes, Pirozzolo has consulted with military training, and he says, “The very last thing you would want to be saddled with is a soldier who is happy, overconfident and carefree.” His point applies to golf just as well. The most effective players aren’t blessedly absent of doubt. They’re the ones who know where the problems lie, and how to avoid them.