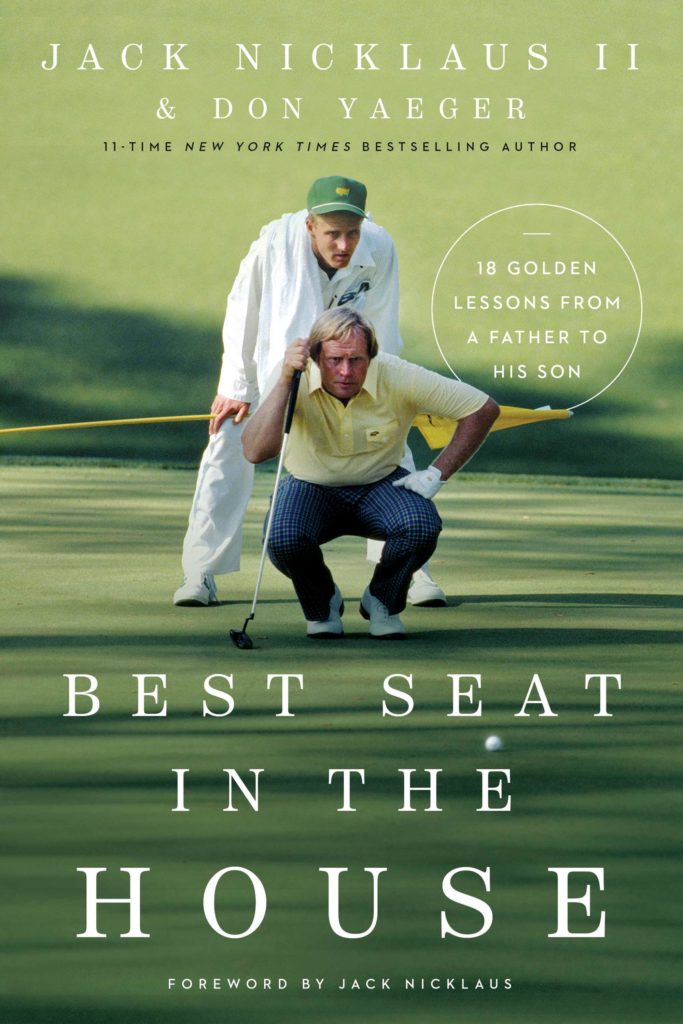

A new memoir by Jack Nicklaus II shares lessons he learned from his father.

As parents, we are often living lives filled with distractions, emotional challenges, and professional and personal disruptions. No matter what you face, take every opportunity you are given to listen to your children. My dad did that so well – even when his

career was at its peak and he was travelling so much – and his actions towards me

taught me to listen to my own children.

Dad patiently and intently listened. He responded with questions about why I thought I might have made certain mistakes as I rehashed my 18 holes. When I told him I was having problems with my chipping, he promised we would work on it when we both got home. He was so interested, generous and genuinely wanted to hear about all of it. When I finally finished, there was a short silence. I was about to thank Dad for calling me and say goodbye.

Then Dad said, “Jackie, would you like to know how your dad did today?”

A little embarrassed, I quickly said, “Well, yes, how did you do today?”

“Well, I just won the US Open.” That was Dad.

The Golden Bear had just set a new tournament scoring record to win his fourth US Open title, at Baltusrol Golf Club in Springfield, New Jersey, and he was on the telephone, some 1,200 miles away, asking me how my round went at a junior golf tournament.

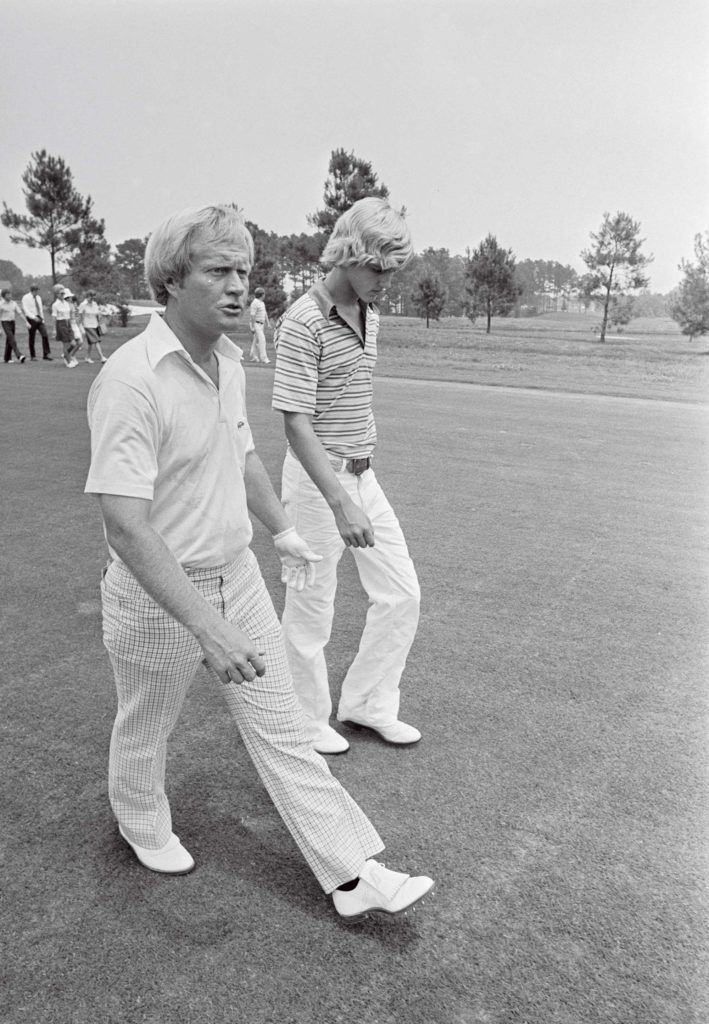

Homework with Dad

After I committed myself to pursuing a career in golf, Dad worked with me to improve my game. He advised me on how to become a better putter, how to be better around the greens with my short game, how to be prepared and how to act like a champion. What he couldn’t help me with were my greatest challenges because he didn’t understand them. Pressure and anxiety weren’t part of his make-up on the golf course. But they were part of mine. Golf is an individualistic sport. Golfers are responsible for what happens to them during a tournament.

Dad just went out and did it!

When I graduated from the University of North Carolina and turned professional, I started sessions with Dr Bob Rotella. Bob was the well-known director of sport psychology for 20 years at the University of Virginia. He focused on the mental aspects of golf, and his lengthy client list included Hall of Fame golfers like Tom Kite and Nick Price, in addition to more modern stars like Rory McIlroy and Padraig Harrington.

Bob once gave me a homework assignment, and it might seem odd, but it was 10 questions to ask Dad. One of the questions I recall was how Dad concentrated on the course when there was so much going on around him. In fact, most of the questions focused on concentration and how Dad consistently performed at such a high level over the course of his career. Dad’s concentration showed in his performances at the elite level. For instance, Dad holds the record for most under-par rounds in the PGA Championship (53) and the record for the most rounds in the 60s in the PGA Championship (41). He played in 156 consecutive Majors (1957 US Open to the 1998 US Open).

I asked Dad the questions, but he never answered them. Dad is rather old school and was reluctant to embrace the benefits of working with a sport psychologist. He wasn’t convinced that Bob could help me. “If I have to concentrate, I just do it,” Dad said. “If I need to shout, I just do it.”

Dad you aren’t really helping me!

To which he shrugged his shoulders and said, “That’s the best answer I can give you.”

What I learned in that moment is that like many elite athletes, Dad couldn’t explain to me what he did that made him special. We all know how few greats actually become great coaches because often what they do, how they think, isn’t transferable knowledge. What I proved was that it wasn’t transferable genetically. That was the last time I tried to get Dad to help me with Bob’s homework questions.

Golf has always been considered the thinking man’s game. There’s much more to golf than striking the ball. Dad’s concentration routine enabled him to fixate on his shots and what he wanted to accomplish. Dad’s focus on the task at hand is legendary and is credited as a major part of his success, especially in the Majors, where he became very difficult to beat. At the Majors, Dad led outright or shared the lead after three rounds 12 times in his career and went on to win 10 of those championships.

Although Dad wouldn’t help me with the homework questions, the exercise led to several really impactful conversations – conversations that went far beyond golf. He shared with me the idea that I would be better at any and everything I would do in life if I would stay locked in on the moment, not worrying about what happened previously or what would happen next. It is almost cliché to say you have to focus only on the things you can control. But I didn’t have to hear Dad say the cliché. I could watch him live it out. This is a lesson he has worked for 40 years to teach me.

And one I will work for the next 40 years to teach my children.

In the arena

I was still playing professionally and in my early 20s when I was partnered with Dad for a round at the Memorial Tournament. I’m not sure what year it was, but Dad had finished on the cut line, and an uneven number of players in the field advanced. Because the round featured twosomes, Dad needed a playing partner, and he asked me. Even though I was only playing alongside my father and was not competing in the tournament, I was honoured but nervous because I had never played in front of galleries that large and under a spotlight that bright.

Because Dad and I were the first twosome off the tee, we served as the pacesetters for the golfers behind us. We had to play relatively fast to ensure a good flow behind us. I got off to a nice start. We got to the sixth hole, and I was two-under par. Dad, on the other hand, was two-over par.

I was probably too nervous to say anything to Dad, but I knew I was playing well. As we walked off the sixth green, I will never forget, Dad said, “You know what? We are not out here to shoot a score. We are out here to be pacesetters. Come on, let’s hurry up, let’s get moving.”

Now I was even more nervous. Sure, I was just playing golf with Dad, but my dad was Jack Nicklaus. This was his arena. And he wanted us to pick up the pace.

On the seventh tee, I hit a duck hook into the woods. I bogeyed the hole while Dad birdied it. Now, I am one-under par, and Dad is one-over par. I bogeyed the next hole to fall to even; Dad parred to remain one-over. Then I double-bogeyed No.9, and Dad birdied. In the span of three holes, I went from a four-stroke lead over Dad to a two-stroke deficit. All this happened after Dad told me to hurry up! I bet you can see where this going. But wait, it actually gets better.

As we walked to the 10th tee, Dad put his arm around me and said, as serious as he could be: “You know what? All these people out here, they really came to watch a show. Why don’t we give them a show? Let’s just slow down and enjoy this.”

Dad won’t admit it, but he was clearly messing with my head. He knew I was whipping him! He knew he wasn’t playing well, so he wanted to play fast. That disrupted any rhythm or confidence I might have had. But then when he started to play well, it was time to slow down. And that messed with my head even further. Dad beat me by a couple of shots, but that was still a big moment for me. He has always been Dad – and always will be Dad regardless of how he’s doing – but that’s another example of how he put his blinders on when there’s an opportunity to compete.

Give and take

Many believe marriage is a 50-50 proposition.

My parents, who will celebrate their 61st wedding anniversary in July 2021, have calculated their own equation for a long marriage. Mum and Dad believe a successful relationship is 95 percent “give” to 5 percent “take” both ways.

That might not sound possible, but they have proven otherwise. Two key elements are required to make this work: (1) Neither party can keep a scorecard of places where they’ve given “in” to the other for purposes of comparison. (2) Both have to be committed to the 95 percent give, 5 percent take model. This can also sound quite complicated. How could both of them give 95 percent?

It took writing this book for me to realise that my parents began every discussion about family plans with each of them thinking first of the other. By doing that, they found a relationship rubric that didn’t just allow both of them to live fulfilled lives. It allowed them to raise five pretty successful children. As I have sat down with my parents to discuss their success, they’ve shared how the model has changed over time. But it always began with empathy for the other before their individual needs.

Even though Dad knew his craft as a professional golfer would keep him on the road often, his greatest responsibility was to return home as fast as possible. He vowed never to be away from home longer than two weeks at a time. (I know that might sound crazy to some, but in his profession it’s not uncommon to be gone many weeks at a time.) Other than a 17-day trip to South Africa for a series of exhibitions with Gary Player, I don’t think Dad ever missed that mark when I was young. That’s amazing.

Through the entirety of his marvellous achievements, despite the phone calls from presidents, visits with kings and the adulation from crowds, Dad made being a husband the most important piece of his life. Being a dad was second. When Dad returned home, he didn’t talk golf. His focus was on us. Dad saw golfers on the PGA Tour who had no family life outside of golf and often wondered how they did it.

By being so in sync and living lives in service of each other, Mum and Dad weren’t just a great team. They were incredible role models for us, the five kids. Now they are relationship role models to 22 grandchildren and even to many friends in the community.

Dad is always quick to credit Mum for all of her support, but he’s barely through any sentence about her without Mum interjecting how grateful she was for the hard work he did to provide for us.

Dad was the disciplinarian when he was home, but Mum managed the children and the household while he travelled the globe to play golf. Don’t think for a second Mum didn’t discipline us when Dad was gone.

There were words I uttered as a kid that today wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. They might be words kids hear or see on the internet or television every hour of the day. If I said God’s name in vain, Mum marched me into the bathroom where I had to take a bite from the bar of Dial soap. Call me a slow learner, but Mum washed my mouth out with soap several times. If you haven’t had the experience, it tasted awful! If we did something wrong, Mum took care of it immediately. She did not, as I am told some mothers do, wait until the father comes home to lay the law down. I would later learn Mum did this intentionally because she didn’t want the first conversation when Dad came through the door to involve what he had to do to straighten us out.

Mum believed Dad needed to come home to a happy family to be successful. This entire conversation might sound completely old-fashioned to some younger couples today, but I can only point them at one number – 61. And that wasn’t my Dad’s lowest score on the golf course.

As Dad has gotten older, the percentage pendulum has swung. Today, Dad makes many life adjustments to fully support Mum’s many endeavours. Dad laughed when he said he was lucky to get by the first 50 years in their marriage.

“The first 50 years are the hardest,” Dad joked.

Taken from Best Seat in the House by Jack Nicklaus II and Don Yaeger. Copyright ©2021 by Jack Nicklaus II and Don Yaeger. Used by permission of Thomas Nelson.