At 5-foot-10, 66 kilograms, Justin Thomas, 22, seems too slight and callow to be a good example (let alone a paragon) of the foundational act on which modern professional golf is built.

At least until he springs into his downswing with a driver. Thomas creates a 14.11-degree upward launch angle that is the highest on the US PGA Tour, which combined with the seventh-lowest spin rate makes him the leading exemplar of the “high-launch, low-spin” mantra for ideal impact. The path of his soaring drives, which last year averaged 277 metres, traces the first, best step to succeeding on tour.

“I love hitting driver because the harder I swing, the straighter I seem to hit it,” says Thomas, the winner of last November’s CIMB Classic in Malaysia. “It gives me a lot of wedges into greens. Which gives me a lot of looks inside 12 feet, which is a lot better than putting a 20-footer. When we get going with that approach, low rounds can get lower.”

Sensing the implied flip side is that his high scores can get higher, Thomas adds, “I always want to be an aggressive player, but I don’t think I’m playing low percentage, if that makes sense.”

Considering what’s going on in professional golf, it absolutely does. It’s often said golf is primarily a game of minimising mistakes. But on the professional tours, the priority on mistake avoidance has given way to a widespread style in which the percentage play – the smart play – is all-out golf.

One effect was evident at the start of the 2015-16 wraparound season. Six of the first seven official events were won by young first-timers: Thomas, Emiliano Grillo, Smylie Kaufman, Peter Malnati, Russell Knox and Kevin Kisner, the oldest of the bunch at 31.

Other big time sports have seen similar “go for it” changes. In baseball, the Kansas City Royals based their World Series-winning tactics on aggressive contact hitting intended to cut down on strikeouts. In the NBA, statistics prove that when teams can shoot a three-pointer instead of a two-pointer, they should. And in the NFL, supporting statistics have made going for it on fourth down more common.

Pro golf’s Moneyball breakthrough has come through the ShotLink-based strokes-gained concept. Although the average amateur can best cut strokes by playing more conservatively, statistics show the tour player will have a better chance at success by playing more all out.

Consider any given Sunday on the US PGA Tour. Players in the middle of the pack know that a low score could make a big difference in prizemoney, but a high one will mean relatively little. Ergo, go for it, with little to lose and much to gain.

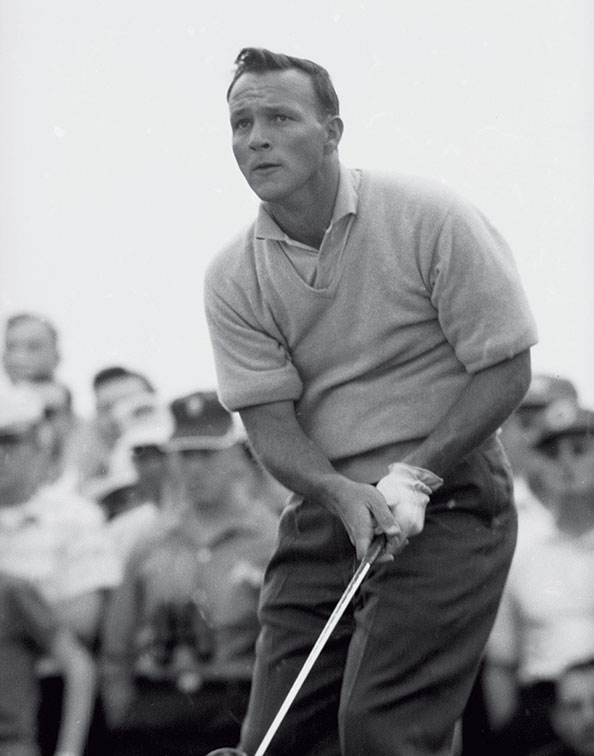

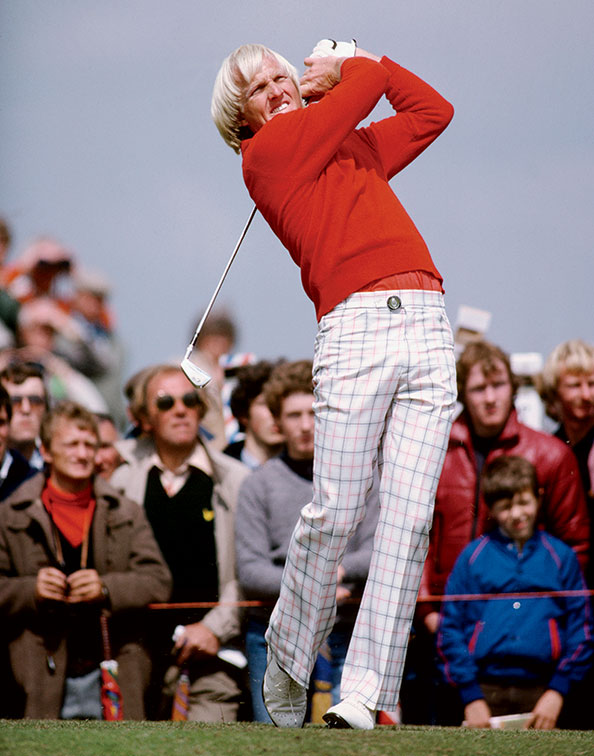

Aggressive golf has always existed. Traditionally such play at big moments has gone down as romantic but foolish, like Billy Joe Patton rinsing risky second shots at the par-5 13th and 15th holes in the final round of the 1954 Masters. Arnold Palmer popularised the phrase “go for broke” with his exciting play-to-win style, which also caused some tragic losses. Lanny Wadkins and Johnny Miller got on some of the hottest pin-seeking streaks ever seen, but the judicious Jack Nicklaus, who always seemed to play well within the outer limits of his immense power, still set the standard of dominance in their era. Greg Norman’s “Shark Attack” strategy was a thrill ride, but he’s still best known for his flameouts.

Phil Mickelson’s 42 official victories have raised the profile of aggressive golf. The downside of his style has been some surprisingly poor golf for such a great player. But when he was being criticised for some foolhardy risks in 2002, the then-Majorless Lefty issued an impromptu manifesto in which he said, “If I change the way I play golf, one, I won’t enjoy it as much, and two, I won’t play to the level I’ve been playing. So I won’t ever change.”

Today, strapping Jamie Lovemark, 27, says he tries to approach the game “kind of like Phil. Either win, come close, or don’t play awesome.”

But the prime shaper of today’s bold style has been Tiger Woods. Though he possessed Nicklaus’ restraint in Majors, Woods executed shots with a transcendent talent that was inspirational.

“More young guys watched Tiger and said, ‘Man, that looks like the way to play golf,’ ” Aussie Stuart Appleby says. Thomas and Jordan Spieth say it was Woods above everyone who shaped them as players. “It’s hard to describe how much,” Thomas says.

Woods’ influence is imbued in Rory McIlroy and Jason Day. And Rickie Fowler reflected the best of Mickelson, his frequent practice-round partner, with uber-aggressive brilliance down the stretch in winning the Players Championship last May.

But the aggressiveness is as common at the mid-level and even lower reaches of the tour. Whether intuitively or by studying statistics, players have figured out that week to week, what matters more than ever is not who’s better, but who’s hot.

Davis Love III, who at 51 won last year at Greensboro, remembers coming out in 1985 as one of the longest hitters ever seen, yet he spent most of his energy trying to gear down for more consistency.

“If you want to win on the tour, you have to lean towards all out, because pretty much everybody else is,” says Love, who as the US Ryder captain is paying close attention to potential members of his team. “Equipment allows you to hit some shots that were more low percentage in the past, and everybody’s hitting it farther. But whatever your style is, if you want to win, it has to be more aggressive. It has to be geared towards making birdies. No matter how hard the course is, somebody shoots a low score every day. You just can’t go out and try to make a bunch of pars. You can barely make the cut anymore doing that.”

Helping the all-out ethos expand has been the improving conditions for tour players. The upside keeps getting higher, and the downside isn’t as low. Here’s a look:

- Winning brings disproportionate rewards.

Beyond 18 per cent of the total purse, winning carries important exemptions, including spots in the Masters, the Hyundai Tournament of Champions and two-year playing privileges. Winning also carries extra weight in the Official World Golf Ranking, where reaching the top 50 means the good life.

Not to mention how winning enhances image and off-course opportunities. - Even the best pros are rarely “on” more than once out of five events.

There’s a saying that 80 per cent of a tour player’s winnings come from 20 per cent of the tournaments. With approximately a fifth of the field playing well in a given week, players know it will take aggressive golf to beat them, which leads to a self-perpetuating style of play. Playing with higher risk might mean more missed cuts, but for a player trying to win, taking a bold approach becomes an intelligent roll of the dice. - Tour pros have less to lose by playing poorly than in the past.

A US PGA Tour player losing his card used to mean a harrowing trip back to Q school, which if unsuccessful, left only mini-tours, foreign tours or Monday qualifiers. Though the original Ben Hogan Tour in the early ’90s did not offer much of a living, what has become the Web.com Tour has created a reasonable safety net, and an opportunity in that tour’s finals to win a card back on the regular tour.

Overall, young players who used to feel they were immediately playing defensively when they got to the tour now have more freedom to go on the attack.

“With my generation, it was make cuts, get a card, keep a job,” says Charles Howell III, 36. “Older players would tell me, ‘Charles, it’s a marathon, not a sprint.’ But now I turn on the TV, and it’s the next 20-year-old hitting it 300m and putting good. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of ‘what if?’ scenarios in their minds. They play fearless golf. Not fearless stupid, but fearless smart. They’ve figured out that it’s just better in today’s game to step on the accelerator.”

Doing so doesn’t have to require power. Among the recent first-time winners, Knox, Kisner and Malnati, although aggressive in seeking birdies, are short hitters who are about accuracy first and being skillful the closer they get to the hole. Knox says he shot at nearly every pin when he won the WGC-HSBC Champions in Shanghai.

“Now all these guys chip like gods,” says veteran Jason Gore, who last year returned to the big dance after five seasons on the Web.com. “It’s like there’s no short side anymore. They fire at the pin even if it’s two [metres] off the back-right edge.”

However, there is no doubt aggressive golf goes best with the power that Thomas described. Even Pat Goss, who coaches two pre-eminent short hitters, Luke Donald and Matthew Fitzpatrick, says, “Ideally, it’s best to hit it far. In developing a young junior player, I would make increasing swing speed and strength a big part of the equation.”

The value of length is reflected in statistics in which the majority of top players rank highly, in particular strokes gained/tee to green and par-4 scoring average. Both are most easily achieved by players who drive the ball long enough to leave the wedge and short-iron approaches that can produce the kind of pin-hunting spin and accuracy that makes getting inside 10 feet with a good shot a realistic goal.

The 10 feet around the hole was quantified by Dave Pelz in the 1980s as the area where good putters make more than they miss.

Long-hitting elite players like McIlroy, Day, Bubba Watson and Dustin Johnson all rank highly in the stats above. But it doesn’t mean they will always beat a hot player who in a given week happens to be doing the same thing even better.

Dealing psychologically with the missed cuts that can come with a higher-risk game can be difficult. “Aggression is fine, but can you handle it when it doesn’t work out?” Appleby says. A good example of someone who did was last year’s rookie of the year, Daniel Berger, who missed 14 cuts but balanced them with six top-10s, including two seconds.

Roberto Castro, whose course-record-tying 63 on the TPC Stadium Course in the 2013 Players Championship was a masterpiece of aggressive play (he hit six approaches inside five feet and an amazing four inside two feet), has made his choice.

“I found I got completely mentally exhausted with a grind-it-out mind-set, and you aren’t going to win many tournaments that way,” Castro says. “I started to just say, ‘I don’t care if I miss the cut or blow this ball into the hazard. At least I tried to hit a good shot.’ I think emotionally and mentally, it was more fun that way.”

As always, the most fun is attained when putts go in. Although top players generally don’t rank as highly in putting as they do in ball-striking statistics, aggression is as vital in putting as any other area of the game at the highest level.

Peter Sanders, who analyses statistics for Zach Johnson and other pros, has found that the six to 10-foot range, which provides the most opportunities in normal pro rounds, separates good putters from not-so-good putters. But, he says, the conversion rate from 11 to 20 feet – Spieth’s greatest advantage over his peers – is consistently what most separates winners in the week of their victories. “Every winner goes off in that range,” Sanders says.

The statistician also tracks proximity to the hole after the first putt, and has found that good putters consistently get the ball to the hole on putts inside 40 feet, where poorer putters leave a lot of them short.

No golfer was more effectively all out than Smylie Kaufman, 24, when he shot 61 to win the Shriners Hospitals for Children Open last October. In a round in which he passed 27 players, Kaufman averaged 300m off the tee and hit nine shots inside 16 feet to rally from a seven-stroke deficit.

“If I get a certain amount under par, I don’t feel limited,” he says confidently.

“I stay aggressive to get more under par. That’s the best way to win.”

It’s getting to be the rule.