The life and death of lieutenant Clyde Pearce, the first native-born winner of the Australian Open.

A small boat landed at Gallipoli at noon on November 13, 1915. On board was Lord Kitchener, the British Army’s Commander-in-Chief, a legendary figure said to have had the best known face in the British Empire next to King George. Kitchener wanted to see for himself what had become a military stalemate. When he stepped off the boat, Kitchener was surrounded by soldiers who, though sick and weary, cheered him keenly.

Army records suggest that Private Clyde Pearce of the 10th Light Horse Regiment also landed at Gallipoli on this day. He may have witnessed Kitchener’s arrival and may even have seen some irony in his low-key landing compared to the hero’s welcome the Field Marshal received.

Pearce had once been a celebrity himself, in sporting circles at least, back in the days when he was the best golfer in Australia. He knew what it was like to be cheered by a crowd; it was just seven years since he became the first native-born Australian Open champion. That mattered for nothing now.

Kitchener stayed for just a couple of hours, during which time he saw enough, it is said, to recommend a withdrawal. Pearce was there for a month. He missed the worst of the ghastly clashes that had cost so many lives, but he still froze through some of the worst of the Gallipoli winter and — according to the 10th Light Horse’s diary — survived “heavy bombing and machinegun fire … Turkish attacks … Heavy shelling … Continuous bombardment …’

In between, there was the ‘silence’. Through late November and December, to set the scene for their departure, the troops were ordered to be quiet and that “no form or any sign of life was to be visible.”

You couldn’t fire a rifle, nor curse the snow. The evacuation became one of the most notable triumphs of the entire campaign. Not a man was lost. Pearce and his comrades left Gallipoli on December 16.

His war had just begun.

Pearce was the second son of Edward and Emmeline Pearce, respected Tasmanians — stalwarts of Hobart’s golfing community. He first came to sporting prominence in 1903, aged 15, playing off scratch in interclub golf matches and finishing 19th at the Australian Amateur Championship.

He had what a Launceston Daily Telegraph story from that year described as a “very orthodox style.”

“[Pearce] does not waste much time in addressing his ball, times well and has a most correct follow through,” the paper continued.

Wiry, strong and athletic, Pearce was fortunate as a boy to receive individual tuition from two Scottish professionals, James Hunter and Edgar Martin, who worked at the fledgling Hobart Golf Club in the early years of the 20th century.

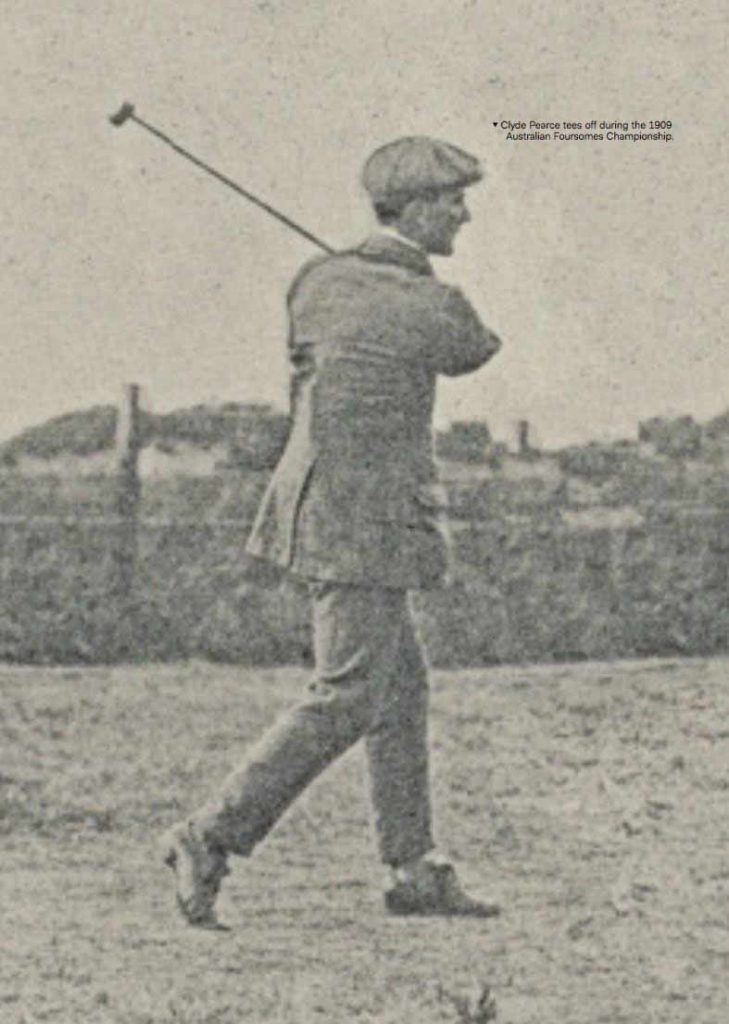

From 1904 to 1910, his name was prominent at Australia’s major golf carnival, which featured the Open and the Amateur Championship. He reached four straight Amateur finals between 1906 and 1909, and claimed the Open/Amateur double in 1908.

Galleries were amazed at how far and straight Pearce — a man of medium height (enlistment papers record him as 5ft 9½in, or 177cm) — could send the ball with seemingly little effort.

A writer using the pseudonym ‘Mid Iron’ analysed his swing for the Australasian and concluded, “There is no ‘hit’ in any sense of that word … it is a pure swing that simply sweeps the ball away, but a very firm crisp sweep indeed.”

An Evening News reporter at the 1908 Australian Open described Pearce’s golf as “drive, approach, long putt, short putt; nothing ever seems to get out of order.”

He was in superb touch one day while playing at Albury in country New South Wales, his round including a hole-in-one at the 180-metre first hole. Afterwards, his vanquished opponent admitted forlornly, “I got so wrapped up watching Pearce play I couldn’t concentrate on the darned game.”

Pearce was, though, a mediocre putter. Photographs show him crouching low over the ball, hands gripping the club well down the handle. The New Zealand Herald reckoned “four comparatively easy (missed) putts” cost Pearce his first Australian Amateur final, against Ernest Gill in 1906.

He began the 1908 Open at The Australian with a course-record 75 and shot the same score in the second round, but then missed 10 putts he should have made during the first 18 of 36 holes on the final day.

Mid Iron wrote that Pearce’s “long game and approaching had been just as fine as ever (but) three (putts) on the green at many of the holes completely neutralised the real excellence of the Tasmanian’s play.”

So upset and confused did Pearce appear during lunch, some observers assumed he was out of contention. But he regrouped to shoot another 75 — a performance so brave and precise it probably remained the finest final round in Open history until Norman Von Nida’s last-day 65 at Royal Melbourne in 1953 (which itself was never challenged as best ever until Jordan Spieth conquered The Australian in 2014).

Pearce then beat Michael Scott 6-and-5 in the semi-final of the Amateur Championship and N.F. Christoe 10-and-8 in the final to do the ‘double’.

It was an impressive feat for one so young. What was most remarkable, the Sydney Morning Herald explained, was that Pearce had been so busy on his brother’s farm he had not picked up a club all year until he arrived in Sydney three weeks before the Open.

It had been clear since his 18th birthday that Pearce was not just a golfer. In 1906, he had left Hobart for Corowa, on the Murray River in the Riverina region of southern NSW, to work on the sheep farm his older brother Roy was managing. Both men joined the Corowa Golf Club and played when they could; the farm would remain Pearce’s base for his annual sorties to Australian golf’s championship week until 1910.

In 1911, Pearce enjoyed an extended tour of Britain and Ireland. He was accompanied by his parents and his younger brother Bruce, an accomplished left-hander and three-time Tasmanian Amateur champion. At the British Amateur Championships, Pearce was knocked out by Bernard Darwin, destined to become one of golf’s finest writers, in the fourth round. Pearce’s one tournament victory came at Peterhead, and he also impressed in Ireland, most notably during the stroke competition at the Irish Amateur Open Championship, when he was second in a ‘blizzard’ so dire many of the refreshment tents at Portmarnock were blown far away.

Immediately after the 1911 British Amateur, Darwin wrote in the London Sunday Times about the “desperate struggle” he and Pearce had enjoyed. “He is a beautifully accurate hitter with all his clubs,” Darwin commented. “If he ever does hit a tee shot crooked, it seems only to occur by the merest accident.”

Seventeen years later, the respected Scottish golf historian Donald Grant recalled Harold Hilton’s victory in this Championship, and how a key factor in Hilton’s triumph was his ability to put enough backspin on the ball so his approach shots stayed on the small, true greens. “(Only) one other player had that shot,” Grant wrote. “Clyde Pearce, Australia, a fine golfer.”

On his return to Australia in November, Pearce was interviewed by the Hobart Mercury. All of 23 years old, he reveals himself as a traditionalist. His greatest respect was for “old school” players, as he called them, who’d learned the game using the gutta-percha ball that went out of fashion around the turn of the century.

“They have the better swings,” Pearce said. “The young fellows ‘hit’ more and are therefore not nearly so certain of their game.”

“Along the Great Southern (railway line) there are a great number of settlers who came from South Australia and Victoria,” Perth’s Western Mail reported in August 1911. “They are progressive men, full of grit and enterprise.” Pearce and another young golfer, the left-handed 1909 Australian Open champion Claude Felstead, were cut from this cloth. The golf community was stunned to learn in January 1912 that the pair had purchased the Chybarlis farm — 2,500 acres of sheep and wheat country located between the townships of Pingelly and Mooterdine in Western Australia, about 160km southeast of Perth.

Both men signed up as members of the fledgling Pingelly Golf Club, with Pearce joining the handicapping committee and offering advice on the layout of the new course. But the Australasian confirmed in August that Pearce and Felstead were “too busily engaged in their business in the West” to contemplate playing in any big tournaments. Twelve months later, Pearce did enter the Western Australian Amateur Championship and the inaugural WA Open, after showing he was in good form by breaking the course record at the Fremantle and Perth clubs, the latter by six shots. In the Open, Pearce found a worthy rival in the English-born Norman Fowlie, but Pearce enjoyed a decisive win with a superb final round. “Up to his second shot at the 17th,” the West Australian said of this performance, “(he) made no mistakes.” His 4-and-2 defeat of Fowlie in the Amateur final two days later was similarly clear-cut.

Of course, we can never be certain what truly motivated Pearce’s decision to sign up for the War. The fact he did so just days after the initial landing at Gallipoli suggests it was more about patriotic duty that any quest for adventure. A number of Pingelly Golf Club members had enlisted, and one, Private Harvey Rae, had been wounded in action, his left arm amputated. Private Rae, from the 11th Battalion, was one of the first to come ashore on April 25, around 4.30am. He was hit by an “explosive bullet” in the early afternoon.

On May 13, Pearce participated in a stroke competition at Pingelly. Except for a couple of rounds he managed to sneak in when on leave from camp, this was his last game of competitive golf. On November 12, Claude Felstead got married in West Perth, though the mood at the wedding was tempered when the groom revealed he was about to enlist.

The next day, Clyde Pearce and Lord Kitchener arrived at Anzac Cove.

For most of 1916, Pearce served in the Middle East. He was quickly promoted to Lance-Corporal, but spent time in hospital — at first irritated by an ingrown toenail then laid so low by cholera. A recommendation for further promotion arrived soon after he returned to duty and on November 13 he was ordered to proceed to Alexandria, Egypt, from where he would sail on the Minnewaska to England, to accept a commission as a second lieutenant, 52nd Battalion. Unfortunately, his journey was interrupted when the Minnewaska hit a mine laid by a German U-boat off Souda Bay, Crete, and was fortunate to make it to shore. No lives were lost but the one-time ocean liner was ruined.

On May 10, 1917, the West Australian revealed that Pearce was in France. “Whilst in Britain (at officer training) he had some golf at Glasgow with some old friends and spent some days of his leave there,” the paper reported. “He has had a month in the front line.”

During that month, Pearce was involved in the great struggles at Lagnicourt, Noreuil and Bullecourt, in France. “No one could have failed to realise what a magnificent officer your son was,” Lt Col Harold Pope, the 52nd’s commanding officer, would recall of these conflicts in a letter to Pearce’s father.

Soon after, the members of the 52nd were dodging shells and machine gun fire during the epic Battle of Messines in Belgium, fighting for strategically important high ground south of the town of Ypres, not far from the French border.

The 52nd Battalion’s chaplain, Rev Donald Blackwood remembered how Pearce “led his men on so splendidly and bravely in the first great charge of June 7,” and how “he did splendid work in organising the new line and repelling counter-attacks.” But Rev Blackwood continued:

“He brought his men out safely from the Messines Ridge on the Sunday morning, had a good rest, and then led them in again to a more difficult bit of work — a more strenuous charge. In this he fell, right in the enemy’s barbed wire. He was there among the first at the head of his men …”

The Australians believed the German wire had been cleared, but this was not always so. Pearce, at the head of his platoon, became trapped, a sitting duck. His Australian Red Cross ‘Wounded and Missing Enquiry’ file contains the following accounts:

Corporal Henry Butler: “He was my platoon officer. I saw him killed by machinegun fire, on the right of Messines. We were on our way over and he got caught in the wire; he was killed outright — six or so bullets right through him. We went on and gained the objective. We lost a terrible lot then, owing to the wire not being properly cut.”

Corporal George Jones: “I saw Lt Pearce lying dead in the field on the 2nd advance in the Messines stunt. He was within 150 yards of the German trenches, shot through the centre of the forehead. Mears, another stretcher bearer in A Company and Falkner in C Company buried him where he was lying.”

The British won the Battle of Messines, but at a high cost: almost 7000 Australian lives were lost. Corporal Arthur Dowling met a soldier who had tried to carry Pearce out, before realising there was no use. According to Dowling, the great golfer’s last words were brave and heart-rending: ‘I’m all right …’

Clyde Pearce’s death is commemorated at the Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres, which bears the names of more than 54,000 men whose final resting places are now unknown. His grieving parents built a memorial to their lost son, by helping to fund the relocation of the historic Mariners Church — which had been situated on the Hobart waterfront — to a new site at Sandy Bay, on part of what was (until 1914) the course of the Hobart Golf Club. A plaque at the ‘new’ Church of St Peter’s, which still stands, remembers Mr and Mrs Pearce’s noble gesture. The tree planted in 1918 in Pearce’s memory on Hobart’s Soldiers Memorial Avenue is well maintained.

In the west, Claude Felstead returned from his stint with the Australian Flying Corps. In 1938, owing to illness, he put his two properties — Chybarlis and the nearby 1300-acre Glen Erne — on the market and retired to the city. He died in Perth in 1964. The clubs with which Felstead won the 1909 Australian Open are on display at Pingelly Golf Club and due recognition is made of his “business partner, Mr Clyde Pearce.”

Elsewhere, as is sport’s way, new heroes emerged and memories began to fade. From the 1930s, Pearce’s name appeared occasionally in golf columns but mostly as a statistical footnote, rarely with any reference to his rare ability and unique backstory. His enormous courage, exceptional poise for one so young and remarkable ability to win big tournaments on a limited preparation was largely forgotten.

This year’s Australian Open will be played almost 100 years to the day since Lord Kitchener and Clyde Pearce landed at Gallipoli. In this year of the Anzac Centenary, Australian golf should pause to remember its greatest hero. It’s not too late.