Why we should remember the Hall of Famer for more than her golf swing.

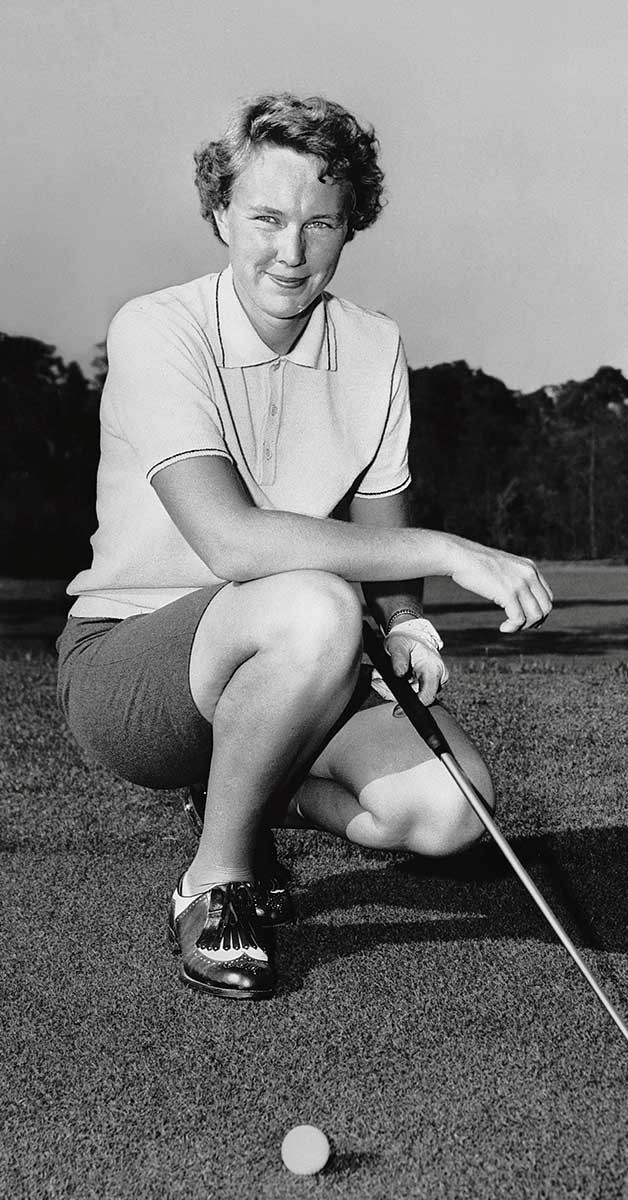

Mickey Wright was a perfect name for someone many thought had a perfect golf swing. It sounded athletic. It sounded like a winner. “Mary Kathryn” had about as much chance against her nickname as Wright’s competition had against her as she won 82 LPGA tournaments, including 13 Major titles.

Wright died of a heart attack in February, three days after her 85th birthday, on Valentine’s Day. Her legend survives both because of what she did (win big with a phenomenal swing) and what she didn’t do (seek a public post-competition life).

The way she played and the privacy she sought revolved around the same thing: control.

The way she played and the privacy she sought revolved around the same thing: control.

When you come up in the footsteps of sweet-swinging Gene Littler, as Wright did growing up in San Diego, delivering club to ball didn’t exactly seem much like forklift to packing crate. “I grew up liking pretty, I think,” Wright told Golf World 20 years ago, “and I guess I still do.”

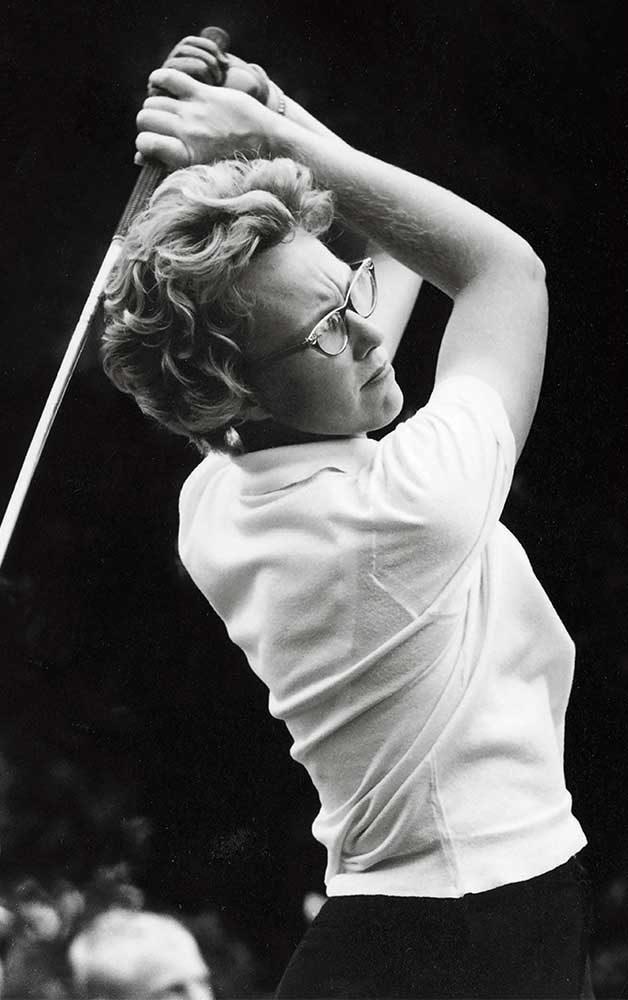

Wright would come to merge good looks with great positions in her action – the whole more than just a sum of her swing’s elements, arresting aesthetically and fundamentally.

“It was just so gracefully athletic,” the late Carol Mann, Hall of Famer and astute student of the game, once observed, “where the club was coming from, how fast it was going and the unloading right at the moment of impact was extraordinary. She was a swinger, but she had one of the volatile impacts. It was almost like a whole new category.”

Wright might not have realised her technique as genius like others did – and do, half a century since her last full season of competition – but she was fascinated by the quest and thrilled by the shots she could hit. In Wright’s playing days, elite women golfers were called “proettes,” but they had to use basically the same unforgiving, heavy-shafted clubs male pros carried. Wright excelled at hitting high-flying long irons, which gave her a huge advantage.

When recollections of Wright switch from how she played to what she won, the focus will always migrate to the period from 1961-’64, when she totalled double-digit victories each year, 44 in the span, a stunning run of success no one has been able to match. Include Wright’s six victories in 1960, and she averaged 10 wins per season over five years. If those five years comprised her whole career, she would rank seventh all-time in LPGA victories, not far from the No.2 spot she eventually occupied. By comparison, just seven PGA Tour players have more than 50 titles.

Wright paid a price for her peak performance. She was the face of the LPGA during that period, and she felt pressure from sponsors and reporters. There were exhibitions to promote the tour and her equipment company. Travel was by car, week after week for long stretches. From a distance, Wright could make golf look easy in the manner of Sam Snead, another star who appeared to have been born with a special gift to swing a club. But appearances belied the effort and practice that went into obtaining and subsequently maintaining that unique talent.

Snead was of a disposition that he wanted to compete as long as he was physically able – that turned out to be until he was in his late 60s. The money games continued for much longer. He could handle not being his best as long as he gave it his best when he was trying to lighten an opponent’s wallet.

Life at the top, however, exacted an emotional toll on Wright. It was similar to what Bobby Jones had experienced decades earlier, giving it everything to reach the summit of the sport, and then deciding it was time to step away even amid the urgings of others that it was much too soon.

Wright didn’t completely disappear from competition following the 1964 season the way Jones did after winning the 1930 Grand Slam at age 28. Yet there would be only three more years (1966, ’67 and ’69) of more than 20 tournament appearances. She won for the last time at the Colgate Dinah Shore Winner’s Circle in 1973, giving friends on tour like Kathy Whitworth hope that she might be energised to play more golf. (Whitworth, the LPGA record-holder with 88 wins, believes that if Wright had played longer, she would have surpassed 100 victories.) That wasn’t the case, although there was an encore in 1979 when, at 44 and wearing sneakers because of a foot problem, Wright lost in a playoff to Nancy Lopez.

Wright would emerge to play with Whitworth in the Legends of Golf in the 1980s and a decade later with three straight appearances in the Sprint Senior Challenge, the last in 1995 when she was 60. In those events, Wright’s swing, honed with plenty of practice, didn’t look much different from the 1960s model. The grace and fundamentals were still there, even if the speed had decreased a bit. Current LPGA members eagerly watched, for the younger ones a chance they didn’t think they would get. Wright’s final full shot was a 4-iron second shot from a tough stance on a par 5. The strike recalled her greatness, set up a two-putt birdie and sent her off happy and content into the competitive sunset. It bothered her to see athletes hang on, the years causing them to display less than what they had been capable of, and she wasn’t going to be one of them.

For the next quarter of a century, golf was a private pleasure, backyard shots off a small faux-turf mat. Awards and anniversaries happened, but Wright enjoyed them from afar. Even when the USGA created a room at the USGA Museum in 2011 to honour her career, Wright, though tickled that it was happening, didn’t make the trip to New Jersey to see it in person.

Calls with a small circle of peers reminded her of the old days, and she kept up with the tours but wondered where the long irons had gone. She was drawn to golfers whose swings flowed, such as Angel Cabrera.

She voiced her views to friends and to reporters who had her phone number in Port St Lucie. Sometimes she didn’t want to talk, but usually she did, and her opinions were insightful and complete. Wright wrote notes and, later on, loved e-mail. That was the way she mentored the young Californian, Lucy Li, who qualified for the 2014 US Women’s Open at 11, the same age Wright was when she started playing golf.

“It is mind-boggling,” Wright told espn.com in 2015 of the precocious wave of golfers. “They are so mature, think so well, have such emotional control. They’re not child-like. It’s like they were raised in another world.”

The standard, though, remains a woman raised much earlier. Figuring out the golf swing is just part of the reason the bar is so high.