Whenever the subject is the 1962 U.S. Open at Oakmont, I think of Arnold Palmer.

By all rights, the mind should go to the winner, Jack Nicklaus. It was his first victory as a pro, and the first of his 18 major championships. He beat the best player in the world, soon usurping him on the way to becoming the greatest player of all time. Oakmont is where Jack’s historic march began.

MORE: Beward the Superstar Curse at Oakmont

But it was Palmer, urged on by thundering crowds on his home turf of western Pennsylvania, for whom the stage was set. The U.S. Open was the major he most coveted, and he was aiming for his second. At age 32, he was in the midst of his greatest year in golf, having just won the Masters, putting the unprecedented professional calendar Grand Slam very much in his sights. He knew that the 22-year-old Nicklaus’ incredible talent was on the verge of erupting, but he thrived on challenge, all the better to make victory more satisfying and provide his legions more thrills.

But at Oakmont, everything went the other way for Palmer. With a corrosive rash of missed short putts over the first 72 holes, Palmer failed to take advantage of some of the best tee- to-green golf of his career and essentially beat himself before being convincingly beaten in an 18-hole playoff. The result unleashed a fully loaded Nicklaus on the landscape, making it probable that Palmer’s own moment of dominance, which had been appearing limitless, would be cut short.

It was an excruciating way to lose, and there was another bad part. In the otherwise rugged Palmer’s softhearted and surely counterproductive way, he felt he’d let down everyone down.

Arnold Palmer playfully punches the chin of Jack Nicklaus after Nicklaus won the U.S. Open at Oakmont.

Bettmann

MORE: Dustin Johnson returns to the site of his major breakthrough

These are the thoughts that occur when I think of Arnold Palmer, the consequence of a way of playing golf that evoked deep feeling. His magnetism was founded showing how much he cared while at the same time seeming to understand and even feel responsible for how much you cared. As has often been said, he let you “in” but that could be a precarious place. There was the greatest joy when he won and the most sorrow—disproportionally, it seemed—when he fell just short. Which rarely, if ever, proved more enduringly true than at Oakmont in 1962.

For Palmer, the knowledge that he remained throughout his life the most popular and perhaps most important golfer in history provided some cushioning for his most jarring defeats. But Oakmont would stand out as the hardest to heal, the loss the great chronicler of all sports, Dave Anderson, said Palmer called “the most hurting of my career.”

It was a pain multiplier because of what it put in motion. For one, it began a pattern that changed Palmer from the clutch finisher to a contender who exhibited fragility at the end of tightly contested majors, most notably at subsequent U.S. Opens at Brookline and Olympic, where he also lost in 18-hole playoffs. Oakmont was the turning point that kept Palmer the player—whose estimable career record of 62 wins, including seven majors, leaves him in the second half of the game’s all-time top 10—from achieving numbers that would have added historical weight more commensurate to his overall impact.

And it cut short what history may decide—with apologies to Jones, Hogan, Woods and, yes, Nicklaus—was golf’s zeitgeist peak, the Age of Palmer. With charismatic comeback victories at the 1960 Masters and U.S. Open, Palmer raised the game’s position in the cultural landscape in a way that made him the first sports superstar of the television age. No one wanted the Palmer party to end, especially because more joy seemed to be in the offing.

Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus pose with their drivers ahead of their U.S. Open playoff.

Bettmann

If he had won at Oakmont that period would have been elongated. As Palmer said of the playoff with Nicklaus decades later to biographer Tom Callahan, “I’ve always believed that if I could have held him off that day, I might have been able to hold him off for a while.” But Nicklaus emerged at Oakmont seemingly fully formed, eliminating any suggestion of fluke to his victory, rather announcing his inevitable succession. As it was, Palmer’s utopian period from 1960 through 1962—in which he won 22 tournaments and six majors—lasted less than three years.

Palmer himself had been intimately attuned to what was coming from the time he first played with Nicklaus in 1958. The two U.S. Amateur victories in 1959 and 1961, and his T-2 in the 1960 U.S. Open and fourth the next year spoke for themselves, but Palmer knew what it took to dominate the game, and he could see Nicklaus had it. “It was clear to anyone who had witnessed his power and finesse and almost unearthly ability to focus on his game that Jack Nicklaus’ moment had arrived,” he wrote in his 1999 autobiography (with James Dodson) “A Golfer’s Life.” “I really did view him as the one man I feared could snatch away the second Open title, one I dearly wanted to win in front of my hometown fans.”

But going into Oakmont, Palmer was a demonstrably better player than Nicklaus. He was in the midst of the best start of his career, having already won six times in 1962, including a 12-stroke victory at Phoenix. His Masters win in a three-way playoff was especially satisfying because he had thrown away the 1961 tournament with a double bogey on the 72nd hole. Although somewhat ominously, the victory included some shaky play in a fourth round 75 that was only salvaged by the kind of late heroics that had come to be expected of Palmer.

He had other reasons to be confident. Although he would win four Masters, as his game matured with greater control, especially with the driver, the U.S. Open became the place Palmer produced his most consistently good golf. He also knew Oakmont, only 40 miles from Latrobe, intimately, having played more than 100 rounds there since the age of 12. This time, he would be performing before fervently supportive throngs whose numbers reached 72,000 for the week, 25,000 more than had attended any previous U.S. Open.

Palmer’s momentum might have been slowed when on the Sunday before the championship he cut the third finger on his right hand while removing luggage from the trunk of his car after the last round of the Thunderbird Classic in New Jersey. The wound was closed by four stiches, with the bandage proving only a minor annoyance at Oakmont. But it was not an ideal preparatory week for Palmer, who had debated pulling out of the Thunderbird to practice at Oakmont and get used to the lightening greens, but chose to honor his commitment to the sponsor. “At best, I was a mediocre putter on very fast greens,” he wrote. “And I probably should have practiced on a similar putting surface prior to the Open. But I didn’t, and that oversight took its toll.”

Nicklaus’ rookie year was marked by early adjustments followed by steady progress. The most highly regarded young player since Bobby Jones started slowly enough to later confess a battle with self-doubt, but after a rocky first month made some adjustments.

Jack Grout reassured him to ignore criticisms of his “flying” right elbow critics at the top of his swing. He also switched back to a stiff flex shaft he long used as an amateur after experimenting with an X flex and started driving it straighter while still bombing it past nearly all his peers, including the long-hitting Palmer. After getting a helpful putting tip at Palm Springs from Jackie Burke, Nicklaus also changed out the light Ben Sayers wooden shaft blade he had used in his last two years as an amateur for a heavier Bristol Sportsman Wizard 600, a heel-shafted flanged model that remained a mainstay for years.

He went on to finish tied for second at Phoenix, lost in a playoff at Houston (where on the final day a putt that would have been for a birdie turned into a double bogey when the ball hit the metal cylinder of the hole after it had been pulled out of the ground by a caddie frantically dealing with a stuck flagstick).

Nicklaus was also second at the Thunderbird, where the week before, he had gone to Oakmont, beginning a career long tradition of doing early reconnaissance at major championship venues. While he still didn’t have his first victory, he felt it coming at the best possible time.

“Returning to Oakmont on the Monday morning of championship week, I had never been hungrier,” Nicklaus wrote in his 1997 autobiography (with Ken Bowden) “My Story.” “Hopefully it wasn’t too obvious on the outside, but inside I was literally burning with determination—and assurance.”

Nicklaus, like Palmer, saw the national championship as the most important of the four majors, and by athletic temperament and golfing IQ was drawn to its supreme challenge.

“The U.S. Open probably does more to make a man out of you than any other tournament,” he said in 2007. “The competition, what it does to you inside … you have to persevere. I enjoyed the punishment, if that’s what you want to call it. To grind that out and make a score at the U.S. Open makes you proud.”

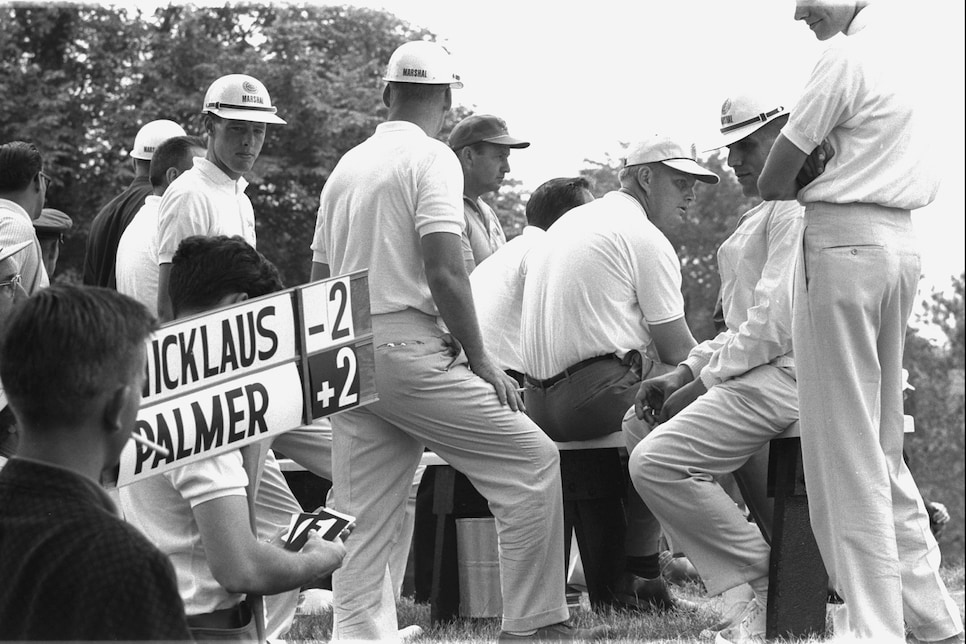

The scoring standard shows Jack Nicklaus leading Arnold Palmer by four shots during their U.S. Open playoff.

Robert Huntzinger

With sense of theater, Joe Dey of the USGA paired Palmer and Nicklaus in a twosome for the first two rounds. And Jack announced himself by birdieing the first three holes as Palmer made early mistakes to fall five strokes behind before rallying to actually edge Nicklaus 71 to 72. Still, Nicklaus’ advantageous length off the tee, and more significantly, the youngster’s imperturbable bearing in the face of the raucous and sometimes abusive pro-Palmer partisans, were noted.

There was no doubt Palmer’s vaunted putting stroke lacked its usual smooth freedom, especially from short range. His morning round of 73 on Open Saturday ending by following a spectacular eagle 2 after driving the 17th green with a three-putt that saw Palmer miss from inside three feet for the third time in the round. “All those careless three putts were killing my psyche,” wrote Palmer, who recorded 10 three-putts over the 90 holes.

By contrast, Nicklaus’ only three-putt of the week came on the first hole of the final round, which dropped him three strokes behind Palmer. Five holes later, after Palmer birdied two of the first four holes, he trailed by five. But Nicklaus patiently played two under par the rest of the way without a bogey to post one under par 283.

Palmer had a chance to go up by four on the eminently birdie-able par-5 ninth. Pin-high in two about 20 yards from the pin, in rough but with plenty of green to work with, Palmer fluffed his wedge shot well short of the green, was weak with his next attempt and missed his par putt from seven feet. “It truly disturbed me that I made 6 when I should have made 4,” Palmer said on the USGA’s 2012 documentary of the championship. “That lived with me all my life and still does.”

Nicklaus demonstrated putting mettle on the par 4 17th, where he faced what he described as an ultra-fast, downhill four-footer for par. Calculating that a dying putt would entail a double break, he decided to hit a firm putt that would take out the break but run at least eight feet past if it missed. “I took a couple of deep breaths, tried to stay very still, and fired,” Nicklaus wrote. The ball hit the back of the cup and fell. After nervously watching the moment on television, Bobby Jones told Nicklaus in a letter that “when I saw the ball dive into the hole, I about jumped out of my chair.”

On the 462-yard 72nd hole, Palmer had an opportunity to make everything right with an ending for the ages after drilling a 4-iron to 10 feet left of the pin. He had a chance to become the first player ever to win the U.S. Open with birdie in the final group on the final hole. But it turned out Palmer’s extraordinary allotment of last-minute miracles to win major championships had run dry. With a stroke more forced than fluid, he pulled his putt wide left. After tapping in for par, Palmer’s dejected demeanor portended that in the upcoming playoff that Sunday, the psychological advantage would lie with the rookie.

In an interview on NBC, Jack Nicklaus looks down at the $15,000 check he won after his playoff defeat of Arnold Palmer in the 1962 U.S. Open.

Robert Huntzinger

And so it played out. Nicklaus started quickly, and when Palmer three-putted the par-3 sixth, he was four behind. He rallied with birdies on the ninth, 11th and 12th to pull within one, but unlike during previous charges in which he felt he could “will” a leader be passed, Palmer wrote “Jack Nicklaus was a different animal altogether, completely unlike anybody I’d ever chased.”

Perhaps disarmed, Palmer pushed his 4-iron on the par-3 13th 60 feet and three-putted yet again. The lead was back to two and Palmer would get no closer, losing the playoff 71-74.

Palmer’s wound was deep, but he was far from broken. Exhibiting sheer doggedness, he would win the next major less than a month later, the British Open at Troon, by six shots. “I’ve never, I mean never, played better golf,” Palmer said at the time.

But there had been a shift. By the beginning of 1963, whether the U.S. Open had done it or not, Nicklaus was all grown up as a golfer. He won the Masters, should have won the British Open at Royal Lytham, and won the PGA Championship. Palmer would win six more times that year but lost another playoff at Brookline in his first year without a major win in the decade. Alfred Wright put it well in Sports Illustrated, writing that Nicklaus had started “a new era before that of Palmer has even begun to ebb.”

After he won his final major at the 1964 Masters, again by a prodigious six shots, Palmer finally did ebb. And when Nicklaus overshadowed that with a nine-shot margin at Augusta the next year, Jones’ famous assessment that “he plays a game of which I’m not familiar” served as a definitive proclamation that the guard had changed.

In that difficult period, Palmer exhibited nobility in a way that only broadened his appeal. “It was hard for Arnold when Jack came along,” sportswriter Jerry Izenberg told Palmer biographer Thomas Hauser. “One day, he was king of the world. And then, probably as early as the U.S. Open at Oakmont, he had the sense that it was just a matter of time before Jack became number one. Nobody likes having their mantle stolen. That throne belonged to Palmer, and the truth is, without Jack, who knows how long Arnold would have reigned. But Palmer handled it with remarkable grace. He kept on trying, he never complained. He was an exemplary sportsman in every sense.”

Years later, a reflective Nicklaus allowed, “I’m not sure that if the tables were turned I could have been quite as gracious as he was.”

Perhaps Palmer was most succinctly captured, not surprisingly, by Dan Jenkins, when in the last line of his classic, “The Dogged Victims of Inexorable Fate,” he designted him “the doggedest victim of us all.” Yes he was. And this year at Oakmont, where Palmer became the only golfer ever to play five U.S. Opens at the same course, we’ll be thinking of him again.

Perhaps Palmer was most succinctly captured, not surprisingly, by Dan Jenkins, when in the last line of his classic, “The Dogged Victims of Inexorable Fate” he designated him “the doggedest victim of us all.” Yes he was. And this year at Oakmont, where Palmer became the only golfer ever to play five U.S. Opens at the same course, we’ll be thinking of him again.

All of the above was Palmer, who Dan Jenkins labelled, in the best final line of any golf book ever, in what happens to be the best golf book ever, “the doggedest victim of us all.” This year at Oakmont, where Palmer became the only golfer ever to play five U.S. Opens at the same course, we’ll be thinking of him again.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com