Informative, controversial, thought provoking, irritating, enlightening. Many words can describe the presentation of Australia’s Top 100 Courses.

It’s not a definitive guide, not that it should be. Nor is the methodology perfect. But for the past three decades, Australian Golf Digest’s biennial ranking has been a source of much debate. Media mogul Kerry Packer opened Ellerston for inspection to our judges simply because he wanted to know where his private estate ranked among the best.

In that regard, the Top 100 has been an essential guide, alerting Australian (and international) golfers to the whereabouts of the finest courses in the land. It has been a tool of change – encouraging clubs to embark upon course improvements.

One of the most satisfying aspects of Australia’s Top 100 Courses has been its consolidation and evolution over time. As an editorial team, we are conscious of making gradual adjustments to improve the ranking. Evolution, not revolution.

This year’s ranking is a case in point. It’s a palatable ranking without any glaring errors. A lot of little kinks have been ironed out from the rankings we published back in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

Twenty years ago we used to bring together a dozen experts to determine Australia’s Top 100. They were: Richard Flood, Tony Gresham, Edwina Kennedy, Alex Mercer, Jack Newton, Craig Parry, Colin Phillips, Tom Ramsey, Peter Senior, Bob Shearer, Lyndsay Stephen and Phil Tresidder, the magazine’s managing editor. They were assisted by seven other panels of experts, which provided separate rankings for each of the six states plus the ACT.

A flaw with this two-pronged methodology was that a course’s position on the national ranking didn’t always correlate with its place on the state-based listing. For example in the 1996 ranking, New South Wales came in at No.4, The Australian at No.5, Royal Sydney No.8 and The Lakes No.9. Yet the state panel had Royal Sydney in front of The Australian.

Another shortcoming was the difficulty of evaluating ‘regional’ courses. This was reflected in generous rankings for Royal Hobart (No.20 in 1996) and Tasmania Golf Club (No.27). This probably emanated from a fear of being too Sydney-centric or Melbourne-focussed. Today, special treatment isn’t needed for Barnbougle Dunes, Lost Farm or Tasmania’s newest entrant, Cape Wickham, which all sit comfortably inside the top-10 layouts in the country.

The Top 100 was conservative in the sense it often took a period of time for a course to find an appropriate slot on the ladder. For instance, The Dunes Golf Links on the Mornington Peninsula entered at No.82 in 1996. That was a poor reflection on what is arguably the most significant course built in Australia over the past 50 years. Tony Cashmore’s layout ushered in a renaissance for links golf, which spawned a host of new courses south of the Murray River. Justifiably, The Dunes is now entrenched as one of Australia’s 20 finest layouts. Evolution, not revolution.

Conversely, there has been a tendency for judges to be overwhelmed, or infatuated, by new styles of courses. A perfect example is Links Hope Island on the Gowickld Coast, which made its debut at No.8 in 1994. It’s just one of several courses that entered the ranking with a bullet before receiving a bit of a correction.

And so as the ranking became more influential in the golf industry, it became imperative we put courses under greater scrutiny. As editor, I made a decision to expand the number of judges and to form a truly national panel. I adopted the criteria used by Golf Digest (US) for its publication of America’s 100 Greatest Courses. A little later, Darius Oliver was brought on board as architecture editor to impart his knowledge of course design and to oversee the whole process of compiling the Top 100.

We now ask judges to score courses on the criteria of Shot Values, Design Variety, Memorability and Conditioning. A total is reached by assigning a mark out of 10 for each criteria (Shot Values is doubled to attain a score out of 20). Having calculated a total out of 50, the judge’s contribution is added to the overhaul pot of scores, enabling the courses to rank themselves.

Incidentally, on the subject of panellists, one of the more amusing emails to be received came after we made a conscious effort to engage with golf clubs about how the Top 100 ranking is compiled. We sent a group email to secretary managers, alerting them to the names of our judges. To our surprise, one executive replied back with words to the effect, “Here’s a list of the people we need to bribe.” We assumed the intention was to forward the email – rather than reply back to the editor of Australian Golf Digest . . . We also assumed the remark was made in jest.

One significant point of difference with Australian Golf Digest’s recent Top 100 rankings is the absence of golf course architects from the judging panel. It should be noted that Oliver – co-designer of the highly acclaimed Cape Wickham – serves in a non-voting capacity.

We concluded that architects have a vested interest in seeing their courses ranked highly. It stands to reason that having them on the panel would compromise the integrity of the ranking. Subsequently, the positive feedback since omitting course architects provides us with ammunition to claim Digest’s Top 100 is the undisputed benchmark for Australian course rankings.

From Resorts to Rocky Coastlines

Golfers in Australia have witnessed an incredible boom during the past 36 years. There are 53 courses in this year’s Top 100 that didn’t exist in 1980. (On top of that, several other courses have undergone major reconstruction that makes them virtually unrecognisable.)

Firstly, there was the sudden influx of resort courses in South-east Queensland and around Perth during the 1980s and 1990s. Peter Thomson, Mike Wolveridge, Ross Perrett, Graham Marsh, Ross Watson and the American Robert Trent Jones Jr all rode the wave of expansion. The great Jack Nicklaus even left his mark.

Next we saw the arrival and phenomenal growth of residential golf developments, which we’ve come to refer to as Living On The Fairway. The propagation of golf estates from America can be traced back to 1989 on the Gold Coast with the opening of an Arnold Palmer layout at the epicentre of the Sanctuary Cove master-planned community.

Property developers saw golf as a means to add value to housing estates. Between 2000 and 2012, more than 40 courses were built with some sort of residential component attached to them. Greg Norman and his former design partner Bob Harrison were at the forefront through Medallist Developments, a joint venture between Macquarie Bank and Great White Shark Enterprises.

But the juxtaposition of real estate and golf course has a somewhat artificial connection. It may go some way to explain why the world rediscovered links golf, the most natural form of the game with its roots in Scotland.

From pure linksland at Bandon Dunes in Oregon to links-style features on Major championship venues at Whistling Straits and Chambers Bay, the ‘running game’ was back in vogue.

Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula emerged as one of the world’s great destinations for links golf following the construction of The Dunes, The National Golf Club’s Moonah and Ocean courses, Moonah Links (Open and Legends) and St Andrews Beach.

Architects embraced the features of links golf around Australia, from Thirteenth Beach on the Bellarine Peninsula across to Kennedy Bay and The Cut in Western Australia to Magenta Shores on the NSW Central Coast. Mike Clayton built his reputation on remodelling courses with strategic design associated with links golf (although some would argue he made his name by ripping out trees).

The appeal of links golf has dovetailed into a worldwide fascination with golf by the seaside and on the clifftops. Barnbougle Dunes and Lost Farm in northeast Tasmania were pioneers. So, too, Kauri Cliffs and Cape Kidnappers on New Zealand’s North Island.

In 2016, the architecture world is salivating over Cabot Cliffs in Canada’s Nova Scotia, Tara Iti in New Zealand and the sibling rivals of Cape Wickham and Ocean Dunes on King Island. Spectacular-looking courses where it seems an objective was to leave the impression of terrain untouched, unblemished, as if Mother Nature had designed it herself.

How Times Have Changed

It’s interesting how the passage of time impacts upon course architecture. Consider The Australian Golf Club, which underwent a major reconstruction by Jack Nicklaus in 1976 at Kerry Packer’s request to increase the difficulty in preparation for the Australian Open. The result was a layout once rated No.2 in the country.

But over the ensuing decades, the course began to look tired and was in need of an upgrade. Putting surfaces had become infested with Poa annua. The intrusion of trees had altered the strategy of holes, blocking views into features and hazards, hindering play and confusing the look of the golf course. Meanwhile, a plethora of new layouts had made The Australian appear lacklustre by comparison.

The club re-commissioned Nicklaus Design four years ago with modernising the course, incorporating the latest design trends. The re-contouring of green complexes and re-shaping of bunkers is now seamless with the surrounding terrain. Gone are the ubiquitous sand traps – replaced by closely mown swales and ankle-high rough with options to play a bump and run, a flop shot or to putt from off the green. The overall appearance is a clean, well-kept parkland look.

The Australian has now hosted consecutive national championships to almost universal acclaim. The new layout showcases the advances in landscape architecture and agronomy. Nicklaus and his design team – sometimes maligned for a cookie-cutter approach to architecture – have shown how they’ve have kept with the times.

Where To From The Golden Age?

Like the Top 100 ranking, the evolution of course architecture is staggering during the past four decades. It’s been a Golden Age of construction in Australia. So what can we expect from the next 40 years?

I hark back to a round on The National Golf Club’s Old Course 20 years ago. The Old Course, if you’re unfamiliar with Trent Jones Jr’s masterpiece, features extremely severe putting surfaces. At one point in the round, the member with whom I was playing said you could hit every green in regulation and not break par. To illustrate the point, he placed my ball at the top of a ridge and dared me to two-putt. I don’t think I stopped the first one within 20 feet of the hole.

The point I’ve taken is you don’t need to surround a green complex with a sea of sand to make a hole challenging. Besides, the distance control of top professionals is so precise that bunkers aren’t the threat they used to be. And it’s a bit of a stretch to describe well-maintained bunkers as hazards for the pros. But for amateurs, playing out of sand is time consuming. How many times have you witnessed a foursome struggling to exit a green surrounded by bunkers? Two of the four are often up to their ankles in sand – chopping, raking, dusting and ventilating.

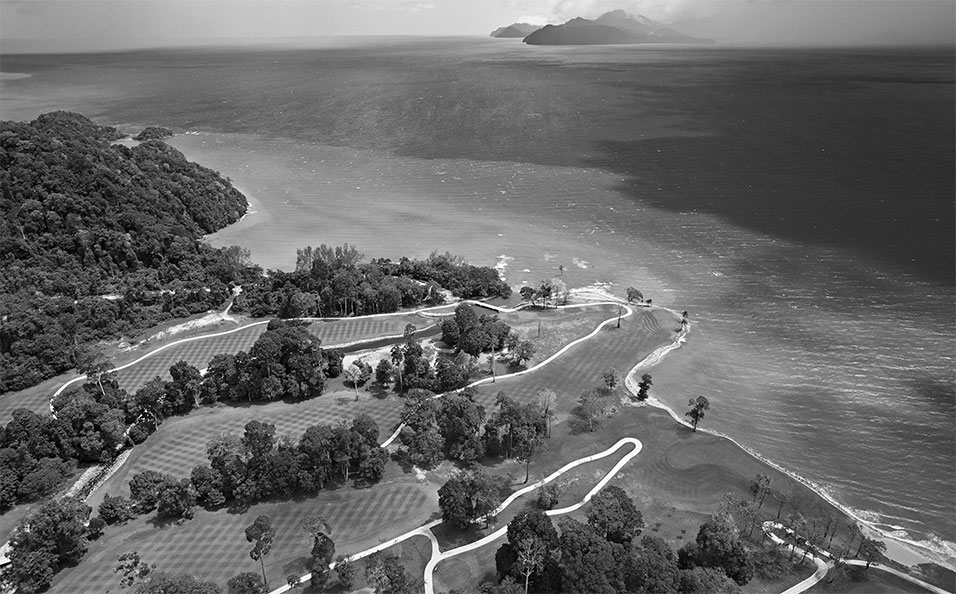

I sense a change in the architectural philosophy of bunkers being the primary type of hazard on a golf course. In 2014, Ernie Els and design partner Greg Letsche reconstructed a course on the Malaysian island of Langkawi without sand bunkers. Set in a rainforest, The Els Club uses towering tropical foliage and creeks to challenge golfers. They felt Langkawi’s annual rainfall would make bunker maintenance a nightmare.

I guarantee new trends will emerge in terms of style. Increasingly, we’re seeing rustic bunkering with wild, windswept, jagged edges. However, the zeitgeist towards links golf and seaside courses will eventually subside.

We can expect the rate of course construction to slow, perhaps dramatically. After all, the supply of new courses doesn’t match the demand in this country where the rate of participation has fallen. That said, it’s an exciting time for the golf industry in Australia.

Consider that annual tourist arrivals from mainland China breached 1 million for the first time last year. Imagine if those numbers continue to rise and golf tourism becomes fashionable. And as the world becomes a more dangerous place, Australia is well positioned to capitalise on the world tourism market.

Agronomy, maintenance, architectural styles and playing characteristics will affect design and the ranking of golf courses. But one thing is for certain – the very best courses will stand the test of time.