If part of this job is to convince golfers I have worthwhile things to say, I should also tell them when to tune me out. That would be anytime I announce I’ve figured out my golf swing, which I’ll declare every couple of months, and is as believable as a vacation I’m planning on the moon.

The mistake here is alternately simple and complicated. First, the simple: There are no easy fixes in golf, and whenever I expect the gates to better golf to magically swing open, I’m headed for disappointment.

But the reason it’s complicated is that breakthroughs are possible. Improvements do happen, sometimes even big ones, but how we implement and sustain them requires more patience and discipline than many of us realize.

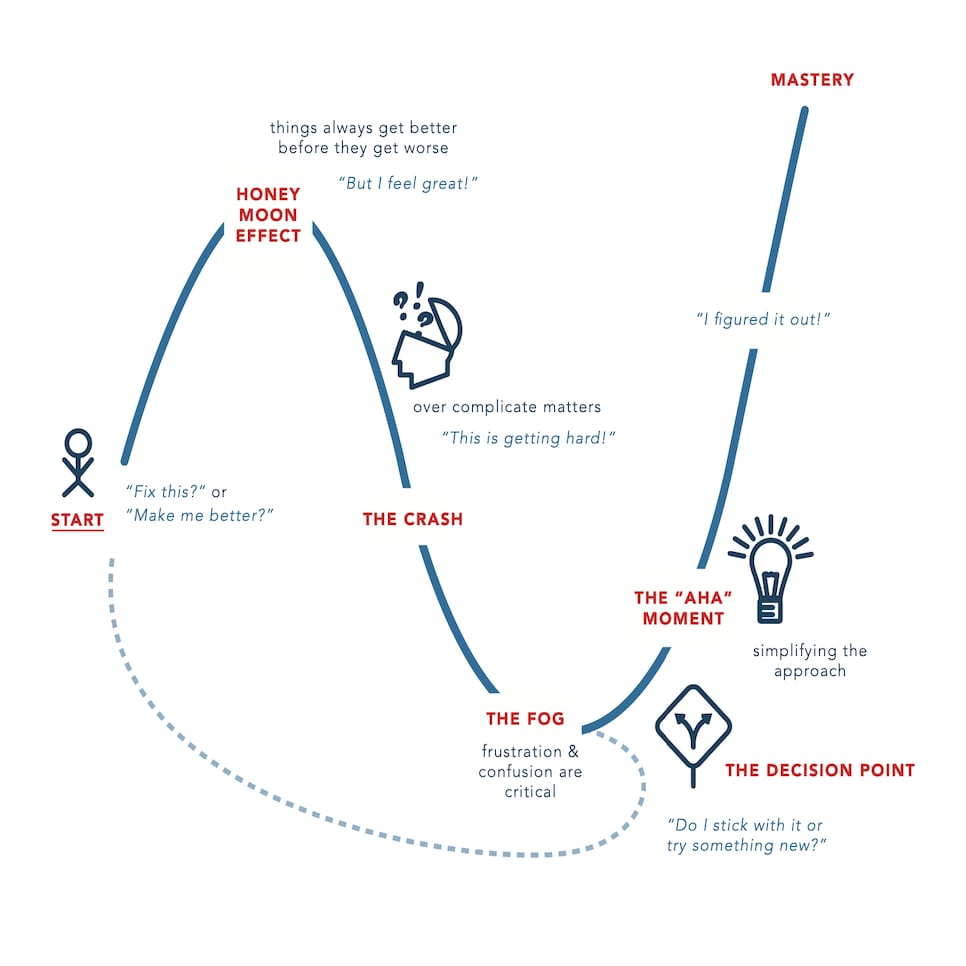

The sports psychologist Bhrett McCabe shared a graphic representation of a typical golfer learning curve that might seem familiar. It looks like this.

The first part of this I’ve already referenced. As common as it is for golfers to be stuck in a rut, we also can emerge from them with renewed optimism. The heady aftermath of a lesson or even just an encouraging practice session is what McCabe calls the “Honeymoon Effect.” In my case recently it resulted from exaggerating the feel of my back to the target at the top of my swing, and then firing to the left side. It worked magnificently for about seven holes. Right up until it didn’t.

This is what McCabe calls “The Crash.” One bad round or even one bad swing is enough for some golfers to question if whatever they were doing is really helping (“The Fog”) and whether they should try something new (“The Decision Point”). Occasionally, that might be needed, but not as often as we think. The critical error is when we abandon a concept too early, because our inability to work through pockets of resistance deprives us of the type of real breakthroughs that stick (“The Aha Moment”).

What we’re talking about is “grit,” a buzzword in sports and beyond, but a quality that extends beyond the obvious examples. Yes, battling back from 4-down to win or playing hurt are signs of grit. But another kind is remaining on task when attention wavers and the reward isn’t clear. As Angela Duckworth, the author of a book and a landmark TED Talk on the subject, has said, it’s often a question of stamina. “Grit is passion and perseverance for very long-term goals,” Duckworth said. In other words, grit isn’t just about how we fight through the hard parts of a challenge, but how we also navigate the mind-numbing, ill-defined middle.

All of this ties back to the missteps golfers like me make at both extremes. It’s never as simple as we think it can be when we’ve found something that works, but it’s also not as dire as a few clunky swings might indicate. When in doubt, outside feedback can help. Especially now when there’s so much free information for everyone to absorb, the mistake is conflating grit with needing to tackle a problem on your own. As Duckworth says, gritty people are more willing to ask for help because they’re committed to solving the problem.

“They rely more on their coaches, mentors, and teachers. They are more likely to ask for help,” the author said in an interview with Education Week. “Grit sounds like being a strong individual who figures things out all by themselves. But gritty people try to find other people to make everything they’re striving to accomplish easier.”