The pub at Frederica Golf Club on St Simons Island in Georgia is a feast for the senses, from the shell-spiked tabby concrete walls to the platters of homemade fried chicken and south Georgia gumbo appearing from the door behind the timber bar where a veteran hand is crushing fresh mint for a tray of Arnold Palmers.

But Lucas Glover is here to work on the Sunday after missing the cut at the Honda Classic, and he will not be distracted. He sits at the corner of the bar with a glass of iced water and a plate with two veggie-burger patties and some sliced avocado in front of him, and he doesn’t even glance at the mound of sauced-up wings being delivered to the member on his left.

It wasn’t always that way.

At 24, Glover was already a PGA Tour winner and a millionaire. And at 188 centimetres and 98 kilograms, he was blessed with the size and easy athleticism passed down from a major-league-pitcher father and NFL-fullback grandfather – which meant he was already ahead in the genetic sweepstakes.

He ate like it, too.

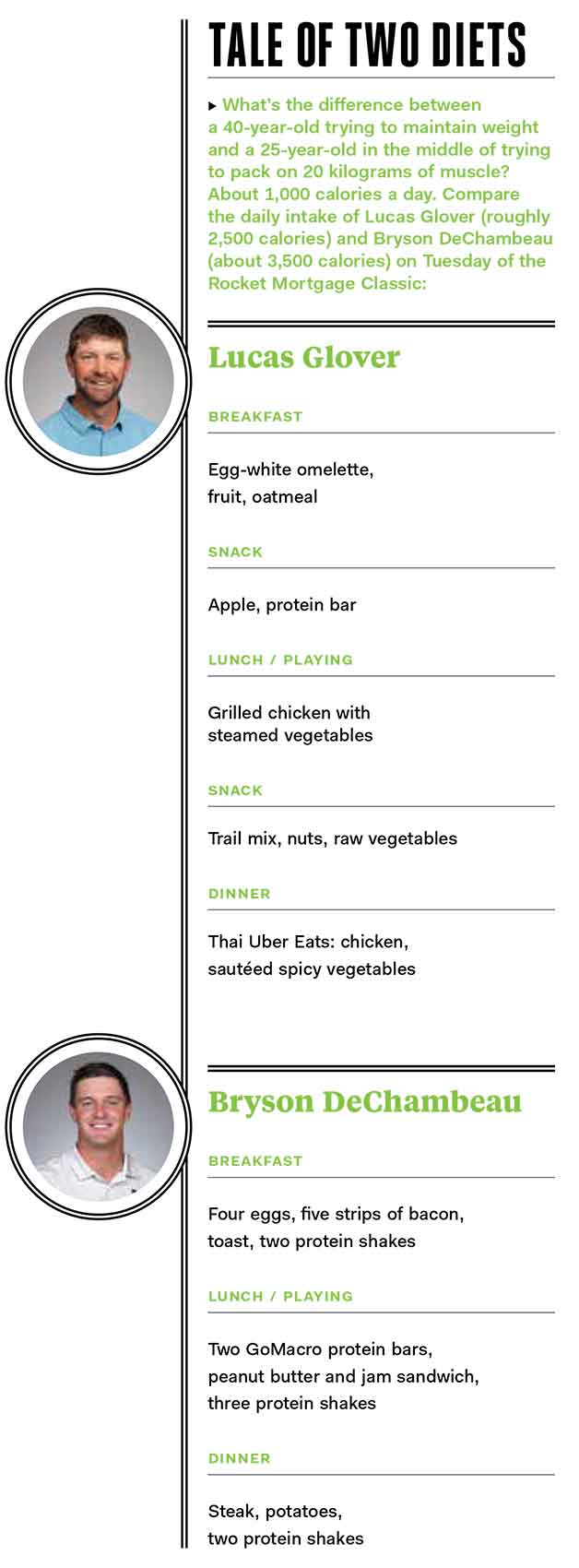

“I just hammered everything they put in front of me. Two entrees. Steaks. I just ate whatever I wanted and never gave it a second thought,” Glover says. “I was young and active, and my metabolism was crazy fast.”

Of course, nobody’s 20s last forever, and neither did Glover’s. He won the 2009 US Open, but a pair of minor knee surgeries and the normal passage of time softened Glover’s body composition to the point where the scales still read the same, but he ached every morning when he got up. He made only seven cuts in 2014, and after another fringy season in 2015, he knew he needed to make some changes.

Of course, nobody’s 20s last forever, and neither did Glover’s. He won the 2009 US Open, but a pair of minor knee surgeries and the normal passage of time softened Glover’s body composition to the point where the scales still read the same, but he ached every morning when he got up. He made only seven cuts in 2014, and after another fringy season in 2015, he knew he needed to make some changes.

“I had been maximising what I did with my teacher and maximising what I did with my trainer, but if I sit around and eat like crap, it’s kind of useless,” Glover says. “I’m old enough to remember when golf was behind other sports, and you’d see guys smoking when they played, and they’d go right to having a bunch of cocktails after a round. At a tour event now, it’d be more surprising to sit down at a table with a guy making a poor diet decision – like some kind of smothered burrito.”

Anybody watching a physical specimen like Tiger Woods, Brooks Koepka or Henrik Stenson hit a shot – or even just walk to his ball – would scoff at the idea that golfers aren’t athletes. Now, the tour is filled with players who train and eat like athletes. Some of them, like Glover, have retooled their diets mostly on their own, with some advice from a trainer.

Another group of high-profile players like Koepka, Stenson, Justin Rose and Gary Woodland have gone a step further, joining athletes in sports like soccer and professional football to hack the entire eating process with help from experts like Dr Ara Suppiah.

A trained emergency-room physician and assistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of Central Florida, Suppiah has a thriving functional sports-medicine practice in Orlando, where he consults with more than a dozen players from the PGA, European and LPGA tours on how to precisely monitor what they eat to maximise performance on the course and in the gym.

“Think about what the demands are in this sport compared to even 15 years ago,” Suppiah says. “You have to hit it way farther, and to do that, you have to train so much harder to stay competitive, which means the risk of injury is so much higher. It means players are looking for an edge and a way to get the most out of their bodies.”

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist – or a medical doctor on the payroll as a consultant – to understand that getting leaner, more muscular and better on the Peloton like Rory McIlroy and Billy Horschel will crank up the clubhead speed and help a player look better in his shirt. But what Suppiah offers is more sophisticated than a workout routine, and probably more important.

Suppiah’s research established that hydration and blood-sugar levels were massive indicators of his players’ performance, especially as they got later into their rounds. “Any degree of dehydration has a huge impact on performance – especially when it comes to emotional and cognitive control,” Suppiah says. “How you react to a bogey or a bad miss, or something you perceive as a bad break, is totally related to your blood-sugar and hydration level.”

Woodland immediately made the connection between what he ate – and when – during a round and his performance, especially on the back nine. “We’re out there playing for five-and-a-half hours, and when you come down to those last four or five holes, you need to have stuff in your body,” Woodland says. “You have to have fuel to do things physically, but more than anything, you have to have fuel in your body so that your mind is in the right place.”

Suppiah walks with every new client on morning and afternoon rounds while monitoring blood-sugar and hydration levels every few holes. He combines that with a thorough panel of bloodwork to get baseline information about a player’s inflammation level, nutrient deficiencies and food sensitivities. At the end, he comes up with a map of what a player should and shouldn’t eat – and when the food should be consumed. That means everything from picking the right time during a round to drink an energy-rich protein shake to laying off a seemingly “healthy” food like spinach because it could be provoking an inflammatory response.

“When people hear about food sensitivities, they might think it means allergies. They’re different things,” Suppiah says. “I’m highly allergic to shellfish, and if I eat it, I need an EpiPen right away, or I need to go to the hospital. I can eat something like rice or red meat and feel fine when I do it, but the next day I’ll feel sluggish because I have a sensitivity. My body has to work harder to produce the energy to digest it. That information is important for an athlete to know.”

A prime example: Rose suffers from intense seasonal pollen allergies – a problem when he goes to a place like Augusta National. In the lead-up to those spring events, Suppiah organises Rose’s diet to build a selection of foods that are low in histamines – the compounds that promote an inflammatory response in the body. High-histamine choices are things like beer, processed meat, cheese, citrus and yes, spinach. A low-histamine meal could include fresh fish, eggs, vegetables and olive oil.

Two-time Major winner Anna Nordqvist started working with Suppiah in 2014, when she started having trouble sleeping. After some tests, she discovered she had allergies and sensitivities to a variety of foods, including gluten and dairy. “I grew up in Sweden, where breakfast usually means a lot of bread,” Nordqvist says. “I’d usually bring a sandwich to the course, but I can’t do that anymore. To get fuel, it meant changing to a protein drink – but we had to work our way through 15 different ones before we found one that I didn’t react to.”

Nordqvist’s diet during a tournament week might sound boring – protein shakes, plain grilled chicken and salmon she makes herself in the kitchen of her Airbnb, and, when convenience is required, a plain chicken burrito with no cheese, beans, rice or salsa from Chipotle – but she says it has radically improved the way she feels, and has helped her sleep and her ability to practise and train without injury. “I can tell you that nobody out there loves to eat clean all the time, but when your body stops aching, and you don’t feel sluggish, as an athlete, that struggle is worth it.”

“When your body stops aching, and you don’t feel sluggish, as an athlete, that struggle is worth it.”

Suppiah uses bloodwork results and technology – which includes a device that constantly monitors a player’s blood sugar from a cuff on the arm – to map the appropriate nutrition-performance plan. “The tests we [do] give a player an outcome,” Suppiah says. “I can look at your amino-acid and vitamin levels and supplement strategically. Players like Brooks Koepka have a chef who travel with them, so I can communicate with that person to put the menu together.”

Koepka, Jordan Spieth, Rickie Fowler and Justin Thomas work together to make those trips to Chipotle obsolete by using the same chef – Michael Parker, who used to run the kitchen at The Floridian, where Koepka’s swing coach, Claude Harmon III, is based. The players either get together and eat in the same house on the road, or they have Parker roam from house to house making meals as needed, Fowler says. “We’re able to get good, quality food, and we know we’re eating clean,” he says. “You don’t want to put a heavy meal in if you know you’re playing early, and that’s where a chef comes in handy. That’s something I’ve put a focus on the past few years for sure.”

Koepka, Jordan Spieth, Rickie Fowler and Justin Thomas work together to make those trips to Chipotle obsolete by using the same chef – Michael Parker, who used to run the kitchen at The Floridian, where Koepka’s swing coach, Claude Harmon III, is based. The players either get together and eat in the same house on the road, or they have Parker roam from house to house making meals as needed, Fowler says. “We’re able to get good, quality food, and we know we’re eating clean,” he says. “You don’t want to put a heavy meal in if you know you’re playing early, and that’s where a chef comes in handy. That’s something I’ve put a focus on the past few years for sure.”

Aside from the competitive advantage of having expertly prepared, nutritious food ready whenever you want it, the chef factor gives players something they prize over almost anything else: control. “When you’re on the road, it’s so easy to lose control of your schedule and end up having to eat bad food,” says Woodland, a self-described non-adventurous eater who will automatically refuse fish before it ever gets to his plate. There’s no shortage of incredible land-based cuisine in and around Pebble Beach, but at the 2019 US Open, Woodland got squeezed by the clock and his quality play. “We were teeing off at 3pm, and by the time I got done practising and doing media, I wasn’t eating dinner until 10,” he says. “By that time, it’s too late to go out, so you’re relying on room service and trying to get enough in your body. You don’t want to add much, just some protein your body can burn through the night.”

The plans Suppiah makes for his clients are detailed and specific to them – which means copying their diets wouldn’t necessarily help you. “General rules that apply to the overall population don’t apply to everyone, and players who are doing this for a living are definitely different than you,” he says. “But there are two things I would call universal truths that are worth it for everyone to know. Keep your blood sugar under control, and understand the things that cause an inflammatory response in your body.”

The sophisticated analysis Suppiah provides his clients can run the same cost as a small used car, but applying some of his basic nutrition advice for even two weeks will help the weekend warrior play better for an upcoming event or trip away.

1. Understand how food affects your blood-sugar levels. “Look at the label on what you eat and add the total protein, fibre and fat and get that number,” Suppiah says. “Compare that total to the number of carbs. If the carbs are higher, it will probably spike your blood sugar and is something you want to avoid.”

2. Manage the inflammation levels in your body. “Foods can have Omega-6 and Omega-3 fatty acids. In simple terms, Omega-6 is more likely to cause inflammation while Omega-3 is more likely to reduce inflammation,” Suppiah says. “You need both, but in hunter-gatherer times, the ratio was about 1-to-1 in the average diet. Now it’s about 20-to-1 Omega-6 to Omega-3. The best way to reduce that ratio? Avoid processed food.”

For Glover, substitutions like the veggie burgers he ate at Frederica have been a revelation. “If you told my 30-year-old self that I’d like them, he would not believe it,” he says. “But they taste good enough that it isn’t a hardship. I’ve found other things like that, too. Sushi is like cheating. You can go to a good sushi restaurant, stay away from the stuff that has rice and pretty much eat whatever you want. Thai food? I’m crazy into the coconut milks and turmeric and lemongrass. It tastes so good, and it’s also anti-inflammatory.”

Through all of it, Glover is still within two kilograms of his weight when he left Clemson University in 2001. But at 40, he’s noticeably sleeker than he was as the 29-year-old US Open champion, and he can wear form-fitting Linksoul clothes popular with tour players 15 years younger. But optics don’t even make the list of reasons he changed what he ate.

“Vanity has zero to do with it. There are like three or four people who see me with my shirt off – my wife and my kids,” Glover says. “It’s all performance-based and for longevity. We got a little later start with kids, and I want to be able to do all the things I want to do with them. I’m never going to be considered a bomber anymore, but I still hit it pretty far. If I keep working out and eating right, the rules of nature say I’ll slow down a little bit, but technology could just continue to go. It’s working for Phil.”