One of the complexities of the potential link-up between the PGA Tour and LIV is what the basic mechanics of playing “together” would look like. Will players who went to LIV be welcomed back to PGA Tour events? Will the two leagues both exist as separate parts of the schedule?

Several top PGA Tour players have expressed open skepticism about LIV players getting a free run back. “There should be a pathway back for them, but they definitely shouldn’t be able to come back without any sort of contribution to the tour, if that makes sense,” said Scottie Scheffler in February. Justin Thomas has taken the same stance: “I’m not in agreement that you should be able to come back that easily. There’s a lot of us that made sacrifices and were true to our word and didn’t make that decision,” he said. “I understand that things are changing and getting better, but I’d have a hard time with that, and I think a lot of guys would have a hard time with that.”

On the other side, players like Dustin Johnson have pointed out that trying to claw back the money they received for joining LIV would just amount to sour grapes from players who wished they had made a better deal. “We’re the ones who took the risk for everything,” Johnson said. “Why shouldn’t we be compensated?”

On a conference call, Dustin Johnson was asked who are some of his favorite players on LIV

"Hard to name them all. We've got so many great ones."

*long pause*

"Myself."

— Christopher Powers (@CPowers14) March 27, 2024

This isn’t the first time competing sports leagues have battled it out, and it certainly isn’t the first time sabers have been rattled by players, owners and league executives during those fights. Even though team sports and franchise ownership are different animals than the individual nature of the PGA Tour, the coming-together stories from those other leagues can be instructive about what we might see when—and if—golf mends its fences.

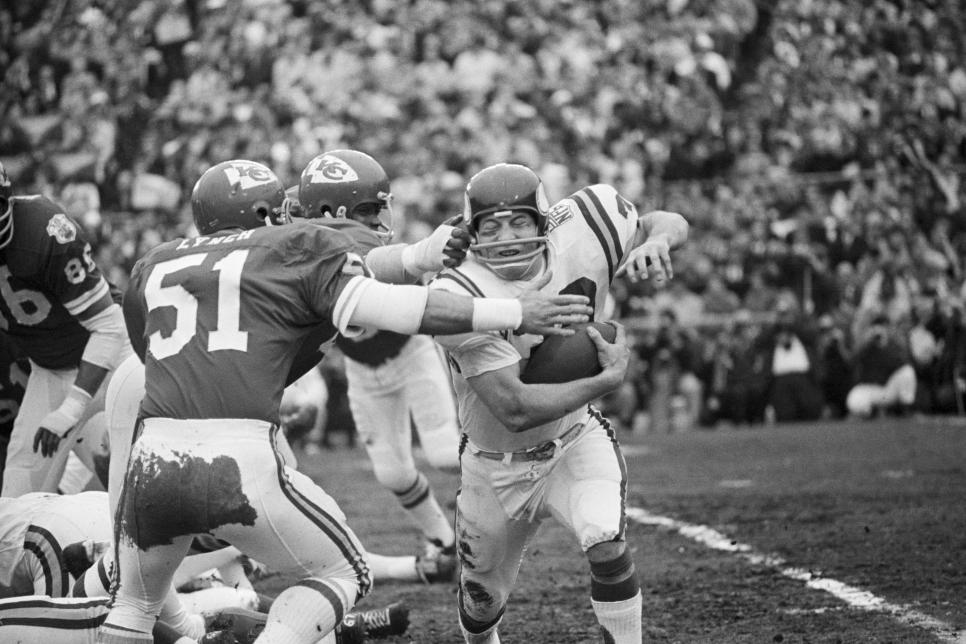

NFL-AFL (1970)

Bettmann

For a decade, the established NFL and upstart AFL waged a high-dollar war for free-agent talent. Where the NFL had legacy and media attention on its side, the AFL’s collection of owners had deeper pockets (sound familiar?) and the willingness to wait out losses to disrupt the NFL’s leadership position. The NFL realized it wasn’t going to spend the AFL out of existence, so it came to the table to make a deal. By 1966, the sides had agreed to the framework for an eventual merger, and the first championship game between the two leagues that year was played in 1967—the Super Bowl. By 1970, the AFL teams became part of the NFL as the AFC, and those owners agreed to pay the NFL $18 million over 20 years. Importantly, the NFL elected to recognize AFL statistics as part of the NFL retroactively, bringing the two leagues into true unison.

More From Golf Digest  Voices The LIV Golf question that the PGA Tour must answer

Voices The LIV Golf question that the PGA Tour must answer  Shouting At Clouds Chris DiMarco says senior pros aren’t paid enough, LIV Golf should buy Champions Tour

Shouting At Clouds Chris DiMarco says senior pros aren’t paid enough, LIV Golf should buy Champions Tour  money Dustin Johnson’s 4Aces brought in a golf business guru. What does that mean for LIV Golf money? NBA-ABA (1976)

money Dustin Johnson’s 4Aces brought in a golf business guru. What does that mean for LIV Golf money? NBA-ABA (1976)

Bettmann

Some of the battles between the NBA and fledgling ABA took the same tone as the NFL-AFL clash. ABA teams signed top players like Julius Erving and Artis Gilmore, and competed directly in big markets like New York City. But the NBA was much more fragile financially than the NFL and made a deal with the ABA to stop the bleeding and capitalize on the excitement the ABA’s rule and marketing innovations had generated. The NBA agreed to accept four of the six ABA teams—the New York Nets (which became New Jersey and eventually moved to Brooklyn), Indiana Pacers, Denver Nuggets and San Antonio Spurs. The two remaining ABA teams folded in exchange for buyouts from the four teams making the jump to the NBA. The Kentucky Colonels received a flat $3 million, and the St. Louis ownership group negotiated a shrewd exit deal that paid them a sliver of the surviving teams’ television revenue in perpetuity. That deal was eventually bought out for $500 million in 2014—more than the entire value of the combined NBA and ABA when the deal was consummated in 1976. Players’ legacy didn’t get treated quite as generously in the transition. The NBA doesn’t recognize ABA records, which means Dr. J’s 11,662 ABA points don’t count toward a career total that would put him in the top 10 all-time if they were combined.

NHL-WHA (1979)

Bruce Bennett

Hockey’s “merger” was perhaps the most brutal. The WHA made a lot of noise signing aging stars like Gordie Howe and Bobby Hull to huge contracts and bringing along young stars like Wayne Gretzky. When the leagues came together in 1979, it was only because the WHA “died” and four of its strongest teams—Gretzky’s Edmonton Oilers and the Hartford Whalers, Quebec Nordiques and Winnipeg Jets—became new expansion teams in the NHL. The original NHL teams even got to take back the players for whom they retained rights without compensating the “new” teams. Like the ABA, WHA records don’t count toward a player’s NHL totals, which means Gordie Howe lost out on the 508 points he scored for the Whalers, and Gretzky doesn’t have the 110 points he scored for the Oilers and Indianapolis Racers added to his career log.

Perhaps two of the most similar analogs to the PGA Tour-LIV dispute are the most obscure for American golf fans. In the mid-1990s, Rupert Murdoch was still an Australia-based media baron, and he was interested in getting a piece of that country’s broadcast rights for top-level rugby. Murdoch’s News Corporation backed the launch of a competing super league to go up against the established Australian Rugby League and drew a collection of teams disenchanted with how the sport was being run and promoted. After years of court battles—and a single year in which the two leagues competed head to head—they agreed to merge into the National Rugby League. Murdoch would end up with a controlling interest in the broadcasting rights for the sport by the mid-2000s.

Then there’s tennis, in which a true professional game has only existed since 1968, when pros were finally able to compete in the four majors. When Jimmy Connors and Evonne Goolagong committed to World Team Tennis in 1974—a new entity with franchises spread across American cities—it caused a disorienting rift in the sport. Connors and Goolagong had each won the first major of the year in Australia, but because they would miss certain European events to play for their teams, they were banned from the French Open. Connors would go on to win Wimbledon and the U.S. Open later in the summer, earning a sort of slam Brooks Koepka would probably appreciate. Connors didn’t play in the French Open from 1974 to 1978—when he was at the height of his career. Chris Evert, John McEnroe and Bjorn Borg all played team tennis, which ultimately made it impractical for majors to hold the line and exclude the world’s best.

MORE: Where did the OWGR come from, and is it becoming obsolete?

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com