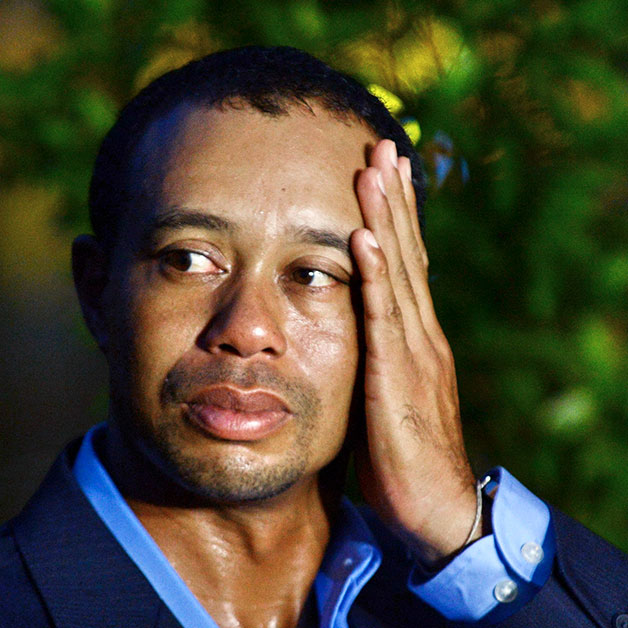

You’ve seen the made-for-tv-movie. Tiger Woods fights through personal demons and spinal-fusion surgery to make a triumphant return to tournament golf. He not only swings the club almost as fast as he did before he got hurt, but he’s a softer, calmer, more relatable character. He even wins the last event of the season after a couple of near misses on the biggest stage.

If it wasn’t real, you’d probably swear it was made up. But it happened. A collection of players and coaches – including, for the first time in one place, all four of the teachers who have worked with Woods during his professional career – are about to describe what they saw as it was happening, and what they think he’ll do in 2019, and beyond.

As for why Woods was able to re-emerge after four years of professional and personal struggle, and what this unlikely second act in his career will ultimately mean in terms of tournaments won, former coach Hank Haney might as well be speaking for the group.

“No matter how unlikely it looks, I don’t ever rule anything out with him,” says Haney, who taught Woods from 2004 to 2010. “Because he’s Tiger Woods.”

• • •

• • •

In October 2017, the progress Woods had been making from anterior lumbar interbody fusion in his lower back had been leaking out from a band of tour-pro friends he joined for matches at the Medalist Golf Club in Hobe Sound, Florida.

Mike Adams teaches at Medalist in the winter, and he watched Woods work his body and game to the point where he was consistently shooting 65 or 66 on one of the fiercest layouts in Florida, while generating a robust 180 miles per hour of ball speed with his driver.

“He was like a boxer, sparring with Rickie [Fowler], Rory [McIlroy] and Justin [Thomas] – players he thought were the best in the world,” Adams says. “He knew that if he could beat them on a hard, 7,600-yard course, he was ready to get back out there.”

Fowler says Woods routinely blew it by him in those games, and Fowler added semi-seriously that he ramped up his prep for the November 2017 Hero World Challenge because he was convinced a reinvigorated Woods was going to be a force.

“He got me thinking I needed to work on my game more,” Fowler says. “He looked great, and the thing I noticed that was different from previous years is that he was going out and playing an extra nine for fun. He was enjoying the game.”

Fowler would go on to shoot 61 in the final round at Hero to win by four, but most people weren’t tuning in to see him win. Woods made his return to the game at that tournament after seven months away, and the world was watching to see what version of Tiger would show up when the shots counted.

It didn’t take long to see that he wasn’t going to play like a junk-ball baseball pitcher surviving on guile and off-speed stuff.

Sean Foley worked with Woods in the four years immediately preceding his first back surgery in 2014. They parted as friends, and Foley was back at the Hero in the Bahamas this past November working with Justin Rose. From his spot on the patio behind the Albany golf-course clubhouse, Foley pointed to the ninth fairway, 400 yards away across a pond. “When did I know it was real? It was right over there,” Foley says. “He had 3-wood from what, 280? He hit that thing, and it landed on the green like a shot put. I said to myself, There you go. Not feeling pain is everything.”

Driver technology and the miracle of modern shafts can turn a small-statured player into a tee-ball-bombing machine. But hoisting a 3-wood off a tight lie to a pin cut just across the water requires more than great equipment. It takes a whole lot of confidence – and raw speed.

Henrik Stenson was playing with Woods when he hit the shot Foley described, and Stenson agrees that the most striking thing about the day wasn’t what Woods shot – he made four birdies, an eagle and two bogeys for a 68 – but that he looked completely comfortable swinging aggressively.

“I thought he was going after the ball very strongly, and he hit it a long, long way,” says Stenson, whose score was three shots worse than Tiger’s that round. “I didn’t really imagine him being able to go flat-out like that. He was ready to play.”

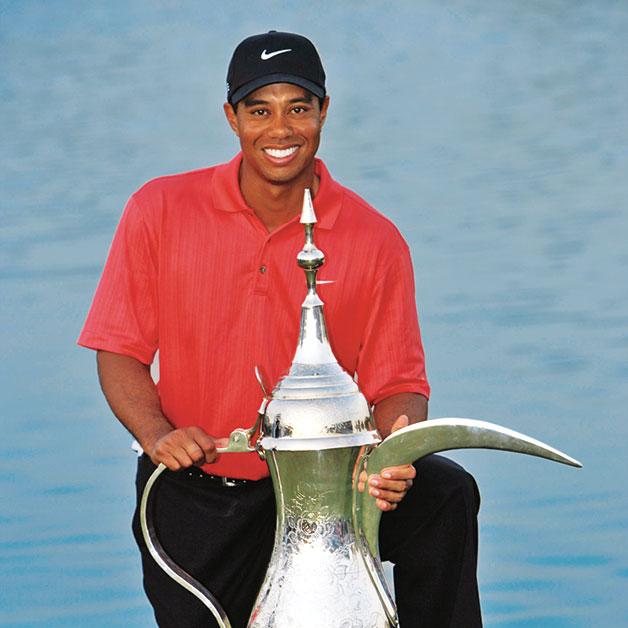

Woods returned to competition two months later at the Farmers Insurance Open. He hovered around par all four days to tie for 23rd, but more important, his back gave him no trouble. After a missed cut at the Genesis Open and a 12th-place finish at the Honda Classic, Woods decided to add another event to his playing schedule to get more early-season reps.

In his debut at the Valspar Championship, Woods got his first taste of genuine contention since finishing T-10 at the 2015 Wyndham Championship. At the Valspar, Paul Casey shot 65 on Sunday to beat Tiger by one stroke and squash what would have been the feel-good hit of the early season, but it was now perfectly clear that Woods was capable of winning again.

Rose was paired with Woods at the Arnold Palmer Invitational the next week and said he knew right away that Tiger’s T-2 finish at Valspar wasn’t a fluke. “The way he was striking the ball, it was as good as anybody out there,” Rose says. “He was looking like the real deal again.”

It didn’t take Haney even that long to make his assessment: “When he posted that first slow swing on Instagram in October [2017], I thought it was a swing he could win with. It looked a lot closer to how he swung when he was incredibly successful.”

And it wasn’t just what Haney saw – it was what he didn’t see. “When he gets his left arm low across his chest and the club across the line at the top, he struggles,” Haney says. “But that was gone.”

Chris Como was Woods’ last official coach, from 2014 to 2017, and the two spent hundreds of hours trying to find an effective swing – a “neutral swing”, Como says – that Tiger could repeat despite the double-digit list of injuries (knee, back, Achilles, etc.) he had endured over his career. Como said he was pleased with the progress they made leading up to the fusion surgery in 2017, and Woods continued evolving in the same direction when he started his most recent rehab.

“Last year, you could see that he had a lot of the general shape of the swing back to when he played his best golf, in the early 2000s,” Como says. “You could tell that he was reconnected with his hands and the release of the club, and he was moving his body in a way that was safe.”

Watch Woods swing in profile, and it still looks like Tiger Woods. He still makes what is one of the most recognisable moves on tour. Yet, several swing coaches agree that his swing looks less “violent” and noticeably different than it was in his prime.

“I’ve studied him pretty hard since the first time he came to the Doral resort in 1997, and I went out to watch him in person at the beginning of 2018,” says Jim McLean. “It was shocking how far he was driving it. He used to have too much lag, and his shoulders were too vertical in the downswing. Now he’s releasing the club. He has to, because he can’t lean on his back anymore.”

McLean describes the swing Earl Woods taught Tiger as a boy as the “Sam Snead style”, with more smooth body flow and clubhead throw. Woods spent two decades trying to get tighter and more controlled, but the last surgery has prompted him to go back to the future, McLean says.

“He’s letting the club go more,” McLean adds. “It’s like he’s throwing the ball nicely down the fairway with his driver. There’s no hang-on move. He’s moving off his right side and opening up nicely, and he has room on his downswing. The guys who drive it well are sweeping the ball, and he’s starting to do that more.”

Foley says the most striking improvement he has seen is how much more space Woods creates in his backswing, especially with the driver.

“I really like how much longer his backswing looks,” he says. “I like how there’s less forward bend from the top. The extra length gives him so much more time to produce speed in the downswing.”

Most of Woods’ commentary about his comeback has a consistent theme – taking what his body gives him and putting himself in position to win again. “I don’t train anywhere near like I used to,” he said in November. “I just physically can’t do it anymore. It’s a different feeling as an older athlete. There are some days you just don’t feel very good. Those are the days I just shut it down. In years past, if I didn’t feel good, I’d go on a five-mile run and make myself feel better. Well, that’s not happening anymore.”

“I don’t train anywhere near like I used to, “I just physically can’t do it anymore. It’s a different feeling as an older athlete.”

– Tiger Woods

If it’s possible, Woods’ body has been even more a subject of conversation than his swing. At the peak of his heavy-training era, Woods was pushing 90 kilograms and filling out his shirt like a footballer. But even that kind of muscle mass couldn’t stabilise his body against the constant punishment of thousands of full-bore swings. But by the end of the 2018 season, he looked a lot different.

“He looks like he’s been more responsible,” Foley says. “He looks really good at 175 or 180 [pounds]. When you see a guy at 200 pounds, with wrists and a waist like this [Foley holds up his thumb and forefinger in a circle], from a proprioception standpoint, your brain becomes unfamiliar with how to move all that mass. And he didn’t need to do it to get longer. How far did he hit it at 138 pounds when he was at Stanford?”

Late last season, Woods says he switched to a driver head with 1.5 degrees more loft – he was using a 9.5-degree head at the Tour Championship – and changed to a slightly lighter shaft so he could produce more height, more spin and a more consistent fade – at the cost of losing what he calls “the hot ones”. He started swinging a comfortable 118 to 120 miles per hour and didn’t hesitate to opt for fairway woods and irons off the tee, playing to his historical strength as a formidable middle- and long-iron player.

Woods led the tour in strokes gained/approach shots in 2018 and was seventh in strokes gained/tee to green. His average clubhead speed was 120.24 mph – faster than Jon Rahm, Justin Thomas and Jason Day. And keep in mind, guys such as Jordan Spieth, Zach Johnson and Francesco Molinari have won Majors swinging slower than 115.

“When he first came back, the speed was him showing off, testing his body out,” Haney says. “I know the radar said he was at 124 or 125mph, but he finished the year 34th in driving distance. It’s one thing to have speed, but you have to be able to use it. What the speed does is let him play around his deficiencies with the driver. If he lost a lot after those surgeries, he just wouldn’t be able to hit all those 3-woods and irons off the tee. He has the speed, but he just uses it a different way than Brooks Koepka and Rory McIlroy do.”

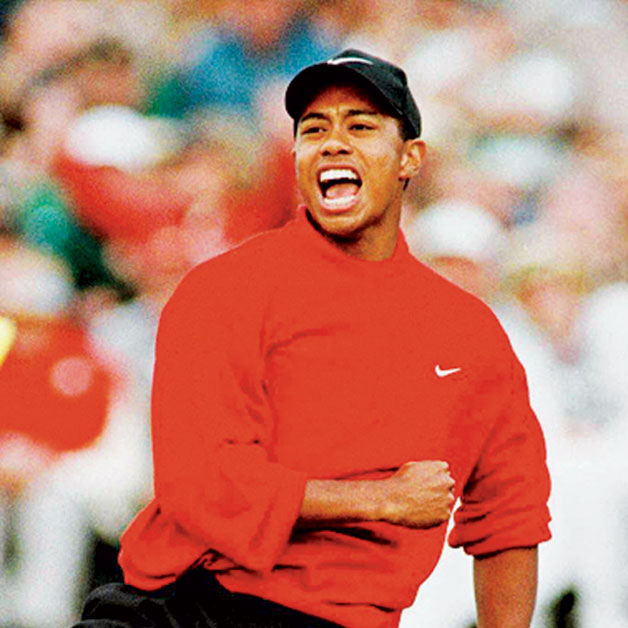

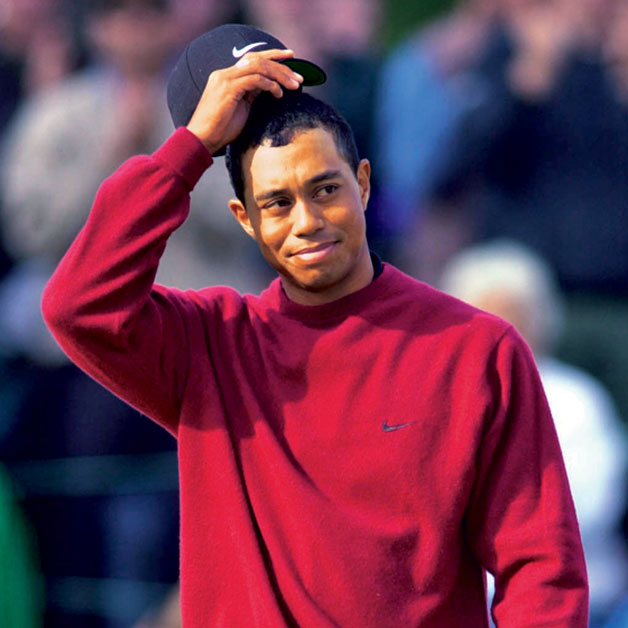

At the Tour Championship in September, Woods closed out his first win anywhere in the world since the 2013 WGC–Bridgestone Invitational with one of his classic game plans – refusing to beat himself while playing from ahead.

“He looked like the old Tiger,” says Butch Harmon, who was his coach from 1993 to 2003, when Woods won eight Majors and 34 US PGA Tour events. “With the lead, he was playing a little fade off the tee and hitting the middle of the green – classic Tiger. He really had complete control over his whole game. He appeared to get away from trying to hit the driver so far and instead got it in the fairway.

“When you think about it, he could have won two Majors in a row earlier in the summer, at the Open Championship and the PGA, so what he did at East Lake was coming.”

Koepka kept Woods from winning the PGA Championship at Bellerive. Afterwards, Koepka said that going toe-to-toe with one of the all-time bests was one of the biggest thrills of his career – and it was serendipitous. Koepka’s coach, Claude Harmon III, closely watched his father, Butch, work with Tiger in the early years of their partnership. Claude says he used what he learned from that experience to help develop Koepka into one of the game’s best players. Claude also went through the same fusion surgery as Woods, which gives him a multi-faceted perspective on Tiger’s comeback and his place in the game today.

“Tiger used to be Darth Vader, and I mean that in the nicest possible way,” Claude says. “He had the theme music. He had the storm troopers, and everybody knew he was coming. But in the last few years, he’s been more like Obi-Wan Kenobi – mentoring people. There are still players who idolise Tiger. Brooks does. But I don’t think there are players who are overawed by him now. He’s been away for a long time. But when he got to the Tour Championship, the speed was back, the swagger was back, the friends-and-family stuff wasn’t there anymore. And I like that.”

Almost lost in all the euphoria over Woods’ driver readings on the speed gun was the dramatic improvement in his short game since his disastrous previous comeback, in early 2015. Where he used to skull basic pitch shots over the green, he’s back to using his wedges as weapons.

“There was one [at Memorial] where he was short of the ninth green on a downslope that was a wet, super-tight lie to a front pin, water hazard everywhere,” Rose says. “He clipped a beautiful shot. That was something maybe he would have struggled with 12 or 18 months prior. When I saw his short game was back and his swing was 100 percent, I knew it was only a matter of time before he won.”

“When I saw his short game was back and his swing was 100 percent, I knew it was only a matter of time before he won.”

– Justin Rose

Woods hit thousands of balls in early 2015 trying to iron out those short-game kinks – which Woods says stemmed mostly from shallowing his full-swing path much more with Como than it had been with Foley – but nerve stingers in his back made settling over the ball comfortably a challenge.

“He did so much work leading up to the Masters in 2015,” Como says. “People remember that incredible shot from 2005 that trickled in on 16, but there was a pitch shot he hit on 12 in 2015, over water, that showed him his short game was going to be on an upward trajectory. He knew that if he was able to get out of pain, it was going to go back to the strength it always had been – and last year, he had an incredible short-game year.”

To a man, every coach in this story says that what Tiger showed last year establishes – health willing – that he can still win more Majors.

“In other sports, they say players lose a step. Tiger hasn’t,” Como says. “His window for winning Majors is still pretty big. Tiger has so many tools in his box that even if his speed drops from where it is, he’s still going to compete.”

Butch Harmon says it looks like Woods has rediscovered his passion for the game and “the sky’s the limit”.

Haney says Woods can return to world No.1, a spot he hasn’t occupied since 2013.

Foley says that Woods’ swing knowledge will let him pick and choose from what he has learned from all his teachers and succeed on his own, no longer needing a formal relationship with an instructor.

“And let’s be honest,” Haney says, “he’s not the easiest to teach, as these young guys found out. He does things his own way, which means he’s exactly where he should be, doing it on his own. He’s going to keep it simple, because that’s where he’s going to have the best success in the shortest amount of time – because he doesn’t have unlimited time.”

A sense of urgency isn’t lost on Woods, but he said he’s entered this season with more optimism – and even better – his best health in at least a decade.

“There’s a precedent for guys having a lot of success in their 40s,” says Woods, who turned 43 last December. “To give myself a legitimate chance to win the past two Major championships – to put myself back in position – I know that if I can put myself there, I can win it.

“Now I just have to do it.”

His Entourage

Tiger woods employs dozens of people to help with his company TGR Ventures and charity initiatives, but when it comes to his on-site support at a tournament, the Woods entourage is surprisingly modest. He hasn’t said he’s working with a swing coach since parting with Chris Como in 2017. His mother, Kultida, and his two children are likely in his gallery at big events, but there’s no personal assistant, and his physical trainer doesn’t hang around, nor do his closest friends – an occasional exception being childhood friend Bryon Bell, who serves as president of Woods’ golf-course design company. If Woods stays in private housing, he’ll likely bring his personal chef, who is paid to cook, not watch him play golf. Oh, and he’ll have man’s best friend in tow when he travels. That would be his bodyguard, the big dude walking nearby who you shouldn’t mess with. But, yes, that also means taking one of his three dogs along on most trips. There’s Taz, Yogi and Bugs. Only a handful of trusted individuals occupy the Woods orbit regularly as he competes. By now, it’s largely a recognisable group.

Mark Steinberg

Woods retained Steinberg as his agent in 1998 after firing Hughes Norton, and in 2011 Woods followed Steinberg from IMG to Excel Sports Management, where Steinberg is a partner and heads the golf division. A native of Peoria, Illinois, Steinberg, 51, attended the University of Illinois and made the basketball team as a walk-on. In a 2016 interview, he said of his relationship with Woods: “We are unwavering in our commitment to each other.” Steinberg’s client list includes the likes of Justin Thomas, Justin Rose and Matt Kuchar.

Glenn Greenspan

Greenspan has been Woods’ spokesman since 2008 after leaving another high-profile job, that of the first director of communications at Augusta National Golf Club and the Masters Tournament. A graduate of Florida State University, where he covered golf for the sports information department, Greenspan, 60, came to Augusta National in 1996. Previously, the New York native worked for the PGA Tour and Gary Player Design.

Joe LaCava

LaCava has been on Woods’ bag since 2011, after working for Dustin Johnson for about four months. LaCava, 55, is a native of Newtown, Connecticut. His cousin, Ken Green, a former PGA Tour player, got him started in the field when he asked LaCava to replace his sister Shelley as his caddie starting in 1987. After three years with Green, LaCava began a 20-plus-year run with Fred Couples.

Rob McNamara

A contemporary who has known Woods since their junior-golf days in Southern California, McNamara is a vice president of Woods’ TGR Ventures. A graduate of Santa Clara University, McNamara, 43, is Woods’ most trusted confidant, and he usually can be seen walking in lockstep with Tiger at a tournament site. McNamara is a scratch golfer who worked at IMG from 2000-’05 before joining Tiger. He knows Woods’ swing and serves as a second set of eyes now that Woods has chosen to go without an instructor.

Erica Herman

Herman made her first public appearance with Woods at the 2017 Presidents Cup, where Woods was a captain’s assistant to Steve Stricker. Herman, 34, was a manager at Woods’ restaurant in Florida, The Woods Jupiter, and now lives with Tiger.

– Dave Shedloski

Tiger-PROOF

Woods says Augusta National “wasn’t that hard” prior to changes

Most golfers consider it sacrilegious to make anything resembling a slight towards Augusta National. In that same breath, while the following from Tiger Woods may convey blasphemy, at its heart is the truth.

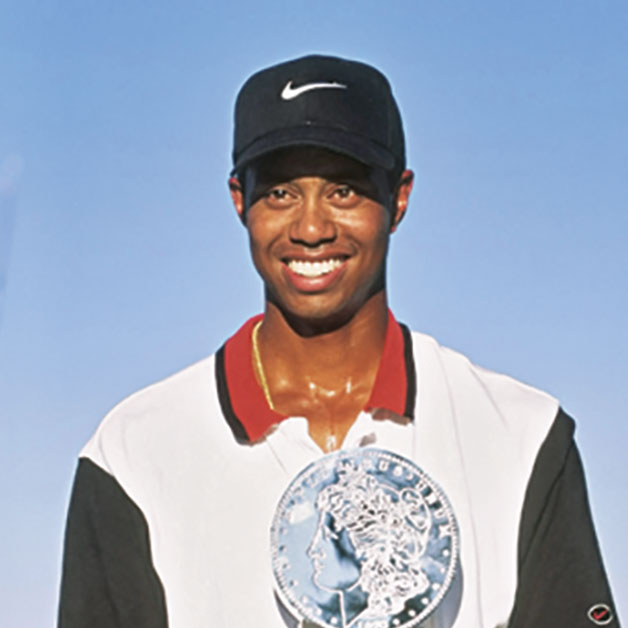

Woods, owner of four green jackets, has often made references that the layout for the Masters “wasn’t that hard.” Easy to say from a player who won the Masters by 12 shots as a 21-year-old. But also an observation shared by Augusta National Golf Club, as the property has undergone an extensive makeover since 2002. A makeover that’s included lengthening holes, moving tee boxes, adding tress, growing the rough a cut higher and narrowing fairways.

A renovation known by another name: “Tiger-proofing.”

You can understand why. During a 2016 tour for Masters.com, Woods went through some of the old club selections went traversing Augusta National.

On hole No.1: “In my earlier years, the right fairway bunker never came into play for me. In fact, I remember hitting driver and 8-iron, 9-iron or wedge to the green in 1995.”

On No.5: “When I first started playing here, I would hit driver over the bunkers on the left side of the fairway and almost reach the crosswalk. I’d be left with a sand wedge to the green almost every day. Now you really can’t do that, and it has changed how I approach this hole.”

On No.9: There was a time when the club used to mow the grass along the inside of the dogleg downgrain and the outside of the dogleg against the grain, so it would bait a lot of us to hug the corner in an effort to get more distance. Now, everything is mowed from green to tee.”

On No.15: “I didn’t have such worries (about accuracy or laying up) in the first round of the 1997 Masters. I hit a driver and a pitching wedge, then made an eagle on my way to a second-nine 30 that helped propel me to my first green jacket.”

However, Woods still maintains Augusta is one of the easiest courses he faces in the year.

“Most of the golf courses I’ve played have been really difficult setups, whether it’s Torrey, LA, Honda, no one went low,” Woods said last May. “Valspar, no one went low, Bay Hill was open and the guys just went low on Sunday only, but for the first three days they were almost kind of just jockeying. Augusta was more wide open than pretty much any event I’ve played in so far this year.”

The course will feature another change in 2019, as the already-formidable fifth hole has lengthened by 50 yards. There will likely be a future alteration to the iconic 13th hole as well, following the club’s purchase of land from neighbouring Augusta Country Club.

Woods, who begins as one of the 2019 Masters favourites, has not won at Augusta National since 2005.