The story of a career relived through the words of golf’s premier writer.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Although there is no world ranking of sports writers, a considerable chunk of Jaime Diaz’s time at the top coincided with Tiger Woods’ respective reign. Once a year for Golf Digest, Diaz – who was awarded the 2012 PGA Lifetime Achievement Award in Journalism – applied his historical perspective and precise style to assessing “The State of Tiger”. These large features were typically informed by one-on-one interviews with the man himself, in addition to a wide range of reputable sources throughout the game. What follows are selected passages. To read them is to relive the suspense of Tiger’s accelerating achievements without the spoil of hindsight.

Perfect at Pebble: 2000

Tiger Woods might disagree, but his performance at the 2000 US Open at Pebble Beach stands as the greatest golf ever played. Though the objective evidence seems irrefutable – 72 holes in a championship-record 12-under par and a 15-stroke margin of victory that is the record for any Major championship – it’s the subjective impressions that best make the case.

When Woods sliced through heavy rough with a 7-iron on Pebble Beach’s par-5 sixth hole with enough force and precision to send his second shot 210 yards over the edge of Stillwater Cove and onto the green during Friday’s round, Roger Maltbie’s early but accurate call – “It’s not a fair fight” – perfectly captured the palpable sense that the proceedings would be more coronation than competition.

Woods arrived at the US Open on Sunday night, staying in a villa behind the 18th green. Immersed in his preparation, he declined to join some 20 other players in a Wednesday-morning memorial service for Payne Stewart along the shoreline of the 18th fairway. “I felt going to the ceremony would be more of a deterrent for me, because I don’t want to be thinking about it,” he said at the time.

Woods was criticised, but Butch Harmon saw an athlete ready for a peak performance. “Tiger was very relaxed and calm, and he had so much confidence in the way he was hitting the ball,” Harmon says. “It had taken a while, but he had gotten into a comfortable slot, feeling like he was taking the club a little outside and up. He was free of mechanical thoughts, and he had this pure aggression. At the same time, his distance control with his short irons was the best it had ever been.”

Indeed, the Woods of 2000 is spectacular in video retrospectives. His leaner body moved with more speed, and though he employed a shorter backswing with less wrist cock than he has in recent years, his sweep through the ball seemed wider and more majestic.

The US Open that year was probably the best driving week of his career. His average of 299.3 yards was the longest in the field by more than six yards, and he ranked 14th in driving accuracy. With shorter approach shots than any other player, and the majority of them from the fairway, Woods led the field in greens in regulation (51) and makeable birdie putts.

“People had been saying that Tiger couldn’t win the US Open because he didn’t drive the ball straight enough,” Harmon remembers. “At Pebble, the first test of the driver is the second hole, which they were playing as a par 4 instead of a par 5, about 480 but narrow as a bowling alley. He got up on that hole on Thursday and carried it 300 yards dead straight. He did that all four days, like he was making a statement. He absolutely drove the ball magnificently.”

But to caddie Steve Williams, then in his second season with Woods, the key weapon was the putter: Woods had no three-putts for the week. He one-putted 34 times and took only 110 putts, sixth-best in the field.

“After a couple of practice rounds,

we both agreed that the greens were going to be the deciding factor because they were very quick, very firm and quite bumpy,” Williams says. “It was going to be very difficult to lag the ball close or chip it stone dead. We knew we were going to have to make a lot of putts in the six to 12-foot range. So that was our emphasis.”

Woods wasn’t happy with his stroke after his practice round on Wednesday and went to the putting green for what became a two-and-a-half-hour session that lasted well into darkness. “The ball wasn’t turning over the way I’d like to see it roll,” he explained. It led to an adjustment in his posture, and his release was fixed.

“The only light was from the little shops beside the green, and we ended up being the only ones there,” Williams says. “But on Wednesday before a Major championship, before you go to bed you want to know in your mind that you’ve got it, that you’re not going to go out Thursday searching. And he found a little key, and he left the green in a really good frame of mind. As it turned out, he putted incredibly. Perfect rhythm in his stroke, perfect contact, perfect speed. The balls just went in the centre. And that was the difference.”

Woods hit only one bad putt in the entire championship, a 10-footer for a double-bogey that he left short and low on the third hole of his third round, when he was momentarily flustered after taking three hacks from deep greenside rough. He made his share of bombs, but the genius of Pebble was how he kept his rounds knitted together with timely short and mid-range putt-ing. “It seemed like any time he made a small mistake, he’d make a great chip or hole a tough eight-footer,” says Jim Furyk, who played with Woods in the first two rounds. “He got everything out of his rounds.”

Tiger versus Jack: 2002

In 110-degree heat (43°C), surrounded by a rocky moonscape in the California desert, the contrast between them never looked so stark. Not only are their ages of 62 and 26 numerical flips, but a 6-iron for one was a 9-iron for the other. They were thick and thin, light and dark, old and young, open and closed, heartland and Pacific Rim, Teutonic and Cablinasian, labouring and lithe. Partners at the made-for-TV “Battle at Bighorn”, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods looked more like the shaky premise for a buddy sitcom than the two most compared athletes from the past and present in the history of sports.

But in the still, silent moments on each tee, the differences fell away. As one addressed the ball, the other turned his legendary focus to every movement and mannerism, hungry to better understand what was special in themselves. Two years before, at the 2000 PGA Championship, in the only time they were paired in an official event, it had taken another prolonged look at Woods for Nicklaus to definitively know that his time had come to stop competing in Majors. Through their elevated senses, Woods has connected with just what it took to win 18 professional Major championships, and Nicklaus understands why Woods has the capacity to win even more.

“It’s kind of amazing how two different people from two different eras who don’t have much contact can feel close,” says Woods, “but we do.”

Not so amazing, actually. Piecing together their shared attributes as golfers would create two detailed mosaics with but a few unfilled spaces. Nicklaus has said there’s not a “nickel’s worth of difference” in their iron play, and you can call their levels of intensity, concentration, intimidation, domination, toughness, resilience, intelligence and tenaciousness a push as well. Both are equally calculating, methodical and consistent. Both built their games around power, stressing the fundamentals. They hit the finest long irons ever seen. From the rough? Wondrous. Extra good on par putts. The more pressure, the more fun. They each love to prepare, excel at peaking and have built their lives around the Majors. Both are perfectionists and supreme egoists, loyal to friends and encouraging to struggling pros. They possess selective memories, were brought up by ultra-supportive parents, believe second place stinks, never quit and have been merciless closers and graceful losers.

Somehow, the cruel game would never turn on them as it did others. “It’s amazing that as many times as he came to the last hole with the tournament on the line, Jack never had a Doug Sanders moment,” says Johnny Miller.

“Jack, and I’m sure Tiger, just believe they’re miracle workers,” says Tom Weiskopf.

Out of respect to the other, they both resist comparisons, Nicklaus because he doesn’t want to appear stuck in the past, Woods because he knows conquering the future means staying in the present. But now that Woods has completed six full pro seasons, there never has been a better time to compare.

Advantage, Nicklaus

With Woods’ talent a given, the heart of the matter is longevity. A close study of Nicklaus shows that he was preternaturally equipped for the long haul, and in some important ways, more so than Woods.

Athleticism: Nicklaus’ early image as Ohio Fats obscured the fact that he was an exceptional all-around athlete. Following the lead of his father, Charlie – who played baseball, football and basketball at Ohio State and was later the Columbus public courts tennis champion – Nicklaus in eighth grade was a switch-hitting catcher on the baseball team, a quarterback on the football team, a sprinter on the track team (11 flat in the 100-yard dash) and a forward in basketball, going on to become honourable mention all-state his senior year.

In all sports, Nicklaus exhibited a knack for the winning moment. “You mean that thing my dad’s got where he makes a 30-footer to win three presses?” asks son Gary. The point is, much like Sam Snead’s, Nicklaus’ longevity was built on an exceptionally tall mountain of physical talent.

Nicklaus at his physical peak in the early ’60s was a marvel to his peers. “As thick as Jack’s hips were, he moved them faster than anyone else on the tour,” says former player Phil Rodgers. “It was startling speed, this truly awesome athletic move, like Tiger’s but with so much more mass. It gave me the same sensation I got watching Jim Brown run.”

Nicklaus governed his power with exceptional feel; he once made 26 straight free throws in a high school competition. “What separates Jack is the sensitivity with his hands,” says teacher Jim Flick. “It is beyond anyone else I’ve ever seen.”

He never focused on becoming exceptionally fit, but Nicklaus had an innate stamina that allowed him to practise for long periods with concentration. “My great gift has been energy,” says Gary Player, “but Jack had as much as I had.”

“Jack was like a Clydesdale,” Rodgers says. “He would just work all day and just go and go and go. I get the sense that Tiger is more of a thoroughbred, maybe more brilliant, but prone to burn out if not handled with care.”

Although there is no denying the classic intersection of speed, power and stability in Woods’ swing, the only time he played an organised sport other than golf was running cross-country in junior high school.

“I would have liked to have played other sports, especially baseball, but I don’t know how good an all-around athlete I would have been,” Woods says. “Probably around JV [junior-varsity] level. I certainly wouldn’t have been any Jim Brown, that’s for sure.”

Normalcy: Nicklaus grew up in a tightly knit, upper-middle-class family in Columbus. His father was a successful pharmacist who was his son’s biggest fan and best friend. Jack took up golf at age 10, but until he won the Ohio Open in 1956, his golf exploits were limited to mostly local junior events. Later, when he became a two-time US Amateur champion, his intention to eschew professional golf and make a living selling insurance sparked little public debate. “I didn’t even decide that golf was a significant part of my life until I was 19,” he says. “By that time, Tiger was public property.”

Since moving to Florida in 1965, Nicklaus has lived in the same one-storey home in North Palm Beach, and all five of his grown children and 15 grandchildren live within 10 minutes. Last year when he followed son Gary at the Memorial Tournament, Nicklaus moved easily among people from his hometown. “As abnormal as Jack’s success has been, it has never overpowered all the very normal things about him,” says Ken Bowden, Nicklaus’ co-author on 10 books. “He has never lost who he is.”

Woods also had a stable upbringing and close relationship with his parents, but from the age of 8 he has led a highly structured life geared to success in competitive golf. Woods has made an uneasy peace with being a public figure; almost in surrender, his favourite pastimes have become solitude-seeking escapes like scuba diving and fishing. “No autographs underwater,” he says, marvelling at Nicklaus’ run at having it all. “What’s so remarkable about Jack is the balance he retained in his life while staying the best for so long,” Tiger said in 2000. “I can already see how difficult that’s going to be for me.”

“Playing badly well”: Over three decades, Nicklaus garnered the majority of his victories while compensating in various ways for a flawed swing. He called it “playing badly well”.

Nicklaus has often said he probably swung the club better as an amateur than as a professional. The 1960 US Open at Cherry Hills and the 1960 World Amateur at Merion are two events where he achieved sensations of effortless control and power that he never was able to recapture.

As a pro, Nicklaus found that the constant travel and changing conditions of tour life made it harder to maintain a groove. Thereafter, he mostly relied on well-conceived Band-Aids and management skills to bring his game up for the biggest moments.

Nicklaus’ knack for self-correction had its source in teacher Jack Grout, who, after imparting the fundamentals, liked to see his students employ trial and error to understand how and why their swings worked. Nicklaus was further encouraged in this approach by Bobby Jones, who had not considered himself a good player until he could diagnose himself. Nicklaus’ emotional control was also vital to accepting less than his best.

“When he was hitting it bad, Jack would find a way to live with it,” Weiskopf says. “Considering his talent and perfectionism, that took an incredible amount of patience. He just refused to get disgusted and beat us with will.”

All in all, says Player, “Jack’s greatest strength was playing junk and scoring 68.” Woods probably plays less “junk”, but he doesn’t live with it quite as well. He seems by perfectionist temperament inclined to fight tendencies he doesn’t like rather than working around them, as his relative lack of second-place finishes indicate. His most recent decision to curtail his work with Butch Harmon suggests he wants to be more self-reliant, in the Jones tradition. Without seeking help at this year’s PGA, an out-of-sync Woods finished second in a Major for the first time.

Style of play: Nicklaus’ tee-to-green style was designed to reduce, not induce, internal stress. In anticipation of the control Jack would need to temper his power, Grout trained him to groove a softer-landing slight fade that made Nicklaus the straightest big hitter ever seen. When he did stray, he tended to play conservative recoveries. But even from the fairway, Nicklaus rarely shot directly at the pin, in part because he was not a great wedge or bunker player.

“In Jack’s mind, his perfect iron shot was 18 feet left of the pin,” Miller says. “His thinking was, It takes all the danger out of play, and now I’m going to make the 18-footer.”

At the 1967 US Open at Baltusrol, Nicklaus hit 61 of 72 greens in regulation, believed to be a record for that championship. As late as 1980, at age 40, Nicklaus led the tour in greens in regulation and total driving.

“Jack seemed to go for broke only when he was behind at the end of a tournament, and it was so impressive,” Player says. “We were probably lucky he didn’t try to do it more often.”

Woods plays a more psychologically wearing style. Because the modern golf ball is flying longer and straighter, he has more incentive to gamble off the tee and with his approaches, but misses leave him with more testing recoveries. Woods’ three most recent Major victories, however, were won in a more Nicklausian style. “Since 2000, I probably haven’t improved that much physically,” Woods says, “but my management is much better.”

Putting: Nicklaus’ approach to putting was the most vital way in which he saved his juice. Once on the green, he stressed correct speed on putts outside 15 feet to leave the shortest possible second putt. His goal of avoiding knee-knockers was helped by the slower green speeds of the 1960s, ’70s and even the ’80s.

“I was a fine two-putter, but sometimes too defensive – too concerned about three-putting,” he wrote in his

autobiography, My Story.

Nicklaus didn’t make every must-have six-footer, but never in 40 years of championship golf did he look less than poised over a big putt. “Jack was always a solid putter,” says Davis Love III. “Then on the back nine on Sunday, he turned into the greatest putter ever.”

Most observers believe Woods makes more long putts than Nicklaus, but he probably misses more short ones. His bolder style, combined with ever-quickening green speeds, forces him to face down more six-footers for par than Nicklaus, and his tendency to ram his short putts can produce lip-outs. Both Palmer and Watson used this style to great success until their early 30s, when with shocking swiftness they became poor short putters, their mental reserves used up.

Compartmentalisation: Though Nicklaus was often second-guessed for having too many interests to focus on golf – whether it was family, course architecture, running his company or hunting and fishing – there is no doubt they kept him energised.

“They allowed me to create diversions in my life, to be able to get away from playing golf,” he says. “When I went back to playing golf, I was able to concentrate and play harder because I was able to

focus when I wanted to focus.”

This ability to hunker down has been severely tested. In the early ’70s, Nicklaus, at considerable financial risk, embarked on the most ambitious project of his life, building Muirfield Village Golf Club. It’s no coincidence, he believes, that “1972 to ’75 was my best golf”. After Nicklaus set up Golden Bear Enterprises with the goal of making enough money to ensure security for generations of Nicklauses, he was devastated in 1985 to discover he was facing the possible ruin of his empire because of the insolvency of two other golf-course developments. One former executive at Golden Bear said the period was so stressful that Nicklaus “was having shortness of breath, basically anxiety attacks”. Nicklaus had to negotiate with bankers in deals that cost him millions, but during that, he produced his greatest victory, the 1986 Masters. Did the financial pressures that Nicklaus felt in the latter half of his career force him to play harder and longer than he would have otherwise? “No,” he says flatly. “I missed some three-foot putts in business. Heck, I missed quite a few three-foot putts in golf, too.”

It’s highly doubtful that the already ultra-wealthy Woods will ever feel similar pressures to keep playing. But without the Nicklaus trait of drawing extra energy from a loaded-up life, inevitable complications will come with time.

Rating the competition: Because Woods will be forced to beat more players capable of winning Majors than Nicklaus did, longevity will be more difficult for him to achieve. “Especially in the ’60s, you’d see a lot of Majors where at the end there would be only five or six guys within 10 strokes,” Rodgers says. “Maybe three or four guys would have a chance to win on the weekend. Today at a Major, you see 20 guys finish within 10 strokes. One of the reasons Jack was able to finish second and third so often is he didn’t have to contend with that kind of depth.”

Much has been made over the assertion that Nicklaus faced a more accomplished and tougher group of players at the very top of the game than Tiger does. The trio that put together the most Major victories against Nicklaus in his first six years – Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Billy Casper – won six in that period. But Ernie Els, Mark O’Meara and Vijay Singh got the same number in the same time against Woods.

Meanwhile, the increased popularity of golf worldwide – directly attributable to Woods – is drawing better and better athletes to the game. As Woods has often said while watching youngsters at his clinics, “Out there, right now, are kids that are going to be better than me. They’re coming fast.”

Anger management: Partly because of natural make-up and partly will, Nicklaus’ temperament was built to last.

Nicklaus has what sport psychologists call a “low arousal” personality. When tournament pressure increased, it generally elevated his intensity to an ideal state rather than overload.

Of course, Nicklaus was the master of dealing with the great career shortener – frustration. It seems that once admonished by his father at age 11 for throwing a club, Nicklaus made the adjustment that most golfers don’t learn until their 30s (and some never do).

“I never once saw Jack Nicklaus lose his poise on the golf course,” says David Graham. “I can’t say that about any other champion I ever played with.”

Although Woods can remain serene in the most pressure-packed moments, he appears to burn much hotter. Woods usually can exemplify what Sam Snead called the ideal state for playing: “cool mad”. But Woods has lost it – slamming clubs or unleashing profanity – on many occasions. “Inside of Tiger burns a volcano, and I’ve seen it erupt,” says his father, Earl. “And it is not nice there.”

Media relations: Considered “too darn sure of myself” in his early years on tour, Nicklaus came to enjoy what he considered his responsibility as the game’s best player to be accessible and co-operative with the media. The expansiveness of his answers earned him the locker-room nickname “Carnac”, after the all-knowing Johnny Carson character, but those who covered him appreciated his willingness to provide insight into his life and golf.

Nicklaus proved his mettle at the 1963 US Open, where as the defending champion he gave long interviews after shooting 76-77 to miss the cut, and most tellingly at the 1981 Open Championship, where he shot an opening-round 83 after learning that his son Steve had crashed his car on the Jack Nicklaus Freeway in Columbus. Nicklaus initially declined to be interviewed but after a few minutes invited the media to his locker and spoke about his round and his emotions as a father. Other than the 1972 season, when he felt invaded by the intense scrutiny his pursuit of the Grand Slam drew, the older he got, the more Nicklaus seemed to enjoy the give and take with the media.

Precisely because of Woods’ impact on the game’s popularity, the media people who cover him are much larger in number and much hungrier for information. Because of Woods’ sensitivity to criticism, it’s not surprising that his group interviews are generally marked by the awkward rhythm of reporters straining to ask penetrating questions and Woods doggedly constructing sterile answers. The week before the Ryder Cup in September, Woods was being peppered about his attitude towards the event when he turned the tables on a questioner. “Let me ask you a question,” he said. “Would you rip me?” But the more Woods withholds, the more the media grasps.

“I never had to deal with what Tiger’s had to deal with,” Nicklaus says. “It’s the hardest thing he’s going to have to deal with.” Says Woods: “I’ll handle the responsibility of doing it, but I don’t have to like doing it.”

Advantage, Woods

Woods might or might not last as long at the top as Nicklaus. Then again, to surpass Nicklaus’ record, he might not have to. What can be ascertained is that his tools are the most formidable ever. “He’s more complete,” Nicklaus admits. “Whatever I had, I think this young man has more of it.”

The mental edge: Nicklaus’ musings about how he thinks on the course have been a model for sport psychologists, but the ability of Woods to produce peak performance by “willing myself into the zone” is unprecedented. Through his Thai background on his mother’s side, Woods has been exposed to eastern philosophy in a way no other great player has. “He carries a real serenity,” says Dr Deborah Graham, “a very Zen-like approach that seems innate.”

Earl Woods, an ex-Green Beret, used techniques derived from interrogation tactics to toughen his son. And at age 13, Tiger began mental training with Dr Jay Brunza, a family friend and psychologist. “His creative imagination and his trust in himself are off the charts,” Brunza says. “You’re working with a Leonardo, and you let the eagle soar.” Among the techniques Brunza used were subliminal tapes and hypnosis. “The first time Jay hypnotised Tiger, he had him stick his arm straight out and told him that it couldn’t be moved,” Earl says. “I tried, but I couldn’t pull it down.”

Woods says he no longer uses tapes or hypnosis. “But I think I used it enough then that it’s inherent in what I do now,” he says. “Everyone had always told me to visualise shots, but I could never see the ball. We worked on a way to look at the target and pull it back into my hands and body, and let my subconscious react. That’s what works best for me.”

Short game: Nicklaus concurs that Woods’ biggest edge over him is in his phenomenal short game.

“You can talk about all the fancy Phil Mickelson flop shots,” says Johnny Miller, “but Tiger has the best short game I have ever seen, especially under pressure.”

“He’s way ahead of everyone,” agrees Rodgers, who helped Nicklaus improve his short game before the 1980 season, when Jack won his 16th and 17th professional Majors.

Woods benefited from being slow to mature physically, in contrast to Nicklaus, who was 5-feet-10 (178 centimetres) and 165 pounds (75 kilograms) at age 13. To keep up with stronger junior golfers, Woods learned how the short game could be an equaliser.

“First of all, I always loved learning all the little shots, so practising was fun,” he says. “Second, I realised it’s impossible to have too good a short game.”

Nicklaus’ short game cost him at least one Major, the 1971 US Open against Trevino. “I asked Jack recently what he would change if he could redo his career,” Flick says. “He said he would have spent a little more time on his short game.”

Work ethic: Although Nicklaus admits he could not sustain the intense practice regimen of his earliest days, Woods has never slacked off. His work ethic is such that he is in the pantheon of practisers. “You work hard on making your weaknesses your strengths,” he says. “I’ve changed a lot of things to get to that point.” Besides being structured and focused, Woods has the advantage of deeply enjoying the act of hitting shots. “Peace at last,” he sometimes sighs when beginning a post-round practice session.

Nicklaus’ first period of laziness snuck up on him after his victory at the 1967 US Open, but it took his father’s death in 1970 to make him realise it. “I had gotten very sloppy,” he said in 2000. “I had wasted time.”

Hand in hand with Woods’ work ethic is a curiosity that differentiates him from Nicklaus. “Tiger is very, very willing to learn and doesn’t buy into the idea that he knows everything,” says Alastair Johnston of International Management Group. “Jack wasn’t called Carnac for nothing.”

Nicklaus isn’t second-guessing his approach, however. “Do I think I could have been better?” he says. “If I had worked at it as hard as some guys work at it today, yeah. But I probably would have had a much shorter career.”

Body: Nicklaus might’ve been more accomplished at other sports, but Woods has superior physical tools.

At 6-feet-2 (188 centimetres) and now 185 pounds (84 kilograms) of lean muscle, Woods has a more classic athletic build, ideally configured to make the huge shoulder turn and restricted hip turn that give the modern golf swing its combination of simplicity and power. The speed at which he moves through the ball demonstrates he has the predominance of fast-twitch muscle fibres that are ideal for explosive movements like the golf swing.

Nicklaus was formidable with his 29-inch thighs and his fast-twitch speed through the ball. But at 5-11 with short limbs, he needed to make a more complicated move – a bigger hip turn and a lifting of the left heel – to achieve the leverage produced more easily by Woods.

Naturally small-boned, Woods was relatively frail at 155 pounds (70 kilograms) when he joined the PGA Tour in 1996. Aware that his fast clubhead speed put his joints at risk and wanting to protect against future back injury by developing a swing based on the big muscles, Woods hit the weights hard in his first few years on tour. More recently, he has altered his physical regimen to push less weight with more golf-specific exercises.

He continues to work on his forearms to better “hold the hit” through impact, he runs to strengthen his lower body and improve endurance, and he does occasional sprints to build more explosive strength on the downswing. During a week of competition, Woods will lift two days and run three days. The former cross-country runner keeps a brisk pace, running four miles in just longer than 30 minutes.

In Nicklaus’ first eight years on tour, he was overweight, ranging between 205 and 215 pounds (93-98 kilograms) as a “compulsive eater”. When Nicklaus noticed how tired he got playing 36 holes on the final day of the 1969 Ryder Cup, he went on a diet, losing 25 pounds and seven inches around his hips. Although the slimmer look improved his appearance, it cost him distance that he never regained. If Nicklaus had incorporated a strength-training program as he lost weight, he might have increased rather than lost power.

The swing: The best players from each succeeding generation almost always have technically sounder swings than their predecessors. Improvements in equipment also lead to style changes. That said, Woods’ swing in relation to his peers’ is biomechanically sounder than Nicklaus’ was.

“They have different body types, so that accounts for a lot of the difference,” David Leadbetter says. “Tiger could make a bigger coil with his left heel on the ground. Jack had massive legs, which allowed him to perhaps be more stable on the downswing. But in terms of pure overall technique, Tiger’s method is slightly more efficient, repeatable, consistent and versatile.”

Many students of the game consider Woods’ swing – from poised address to beautifully balanced finish – to be the closest thing yet to perfection.

“Tiger has no idiosyncrasies,” Nick Faldo says. “If you tried to do some caricature of his swing, exaggerate some mannerism, you really couldn’t.”

Woods’ swing is the result of an obsessive attention since boyhood to incorporate the best traits of the best players. “It was never one person,” Woods says. “I’ve tried to pick like 50 players and take the best out of them and make one super player.”

Nicklaus’ style was revolutionary and superior in key ways to the methods of his peers. With the fullest turn the men’s game had ever seen, his uprightness allowed him to hit the ball high, to the greatest effect with his long irons, and to play from rough with near impunity. But executing such a move required enormous strength and flexibility, for without a tremendous coiling to create sufficient depth, Nicklaus’ club would approach the ball on such a steep angle that consistent solid contact became difficult. “Snead and Weiskopf both hit the ball better than Jack,” Player says. Loss of physical strength was a primary reason Nicklaus was forced in 1980 to make the biggest swing overhaul of his career and flatten his plane.

When it comes to the golf swing, Woods is by nature more technically oriented, experimental and curious than Nicklaus. In 1997, Tiger took the risk of decreasing the hand action and increasing the body rotation in the swing he had used to win the Masters by 12 strokes. With his improved method, Woods has lost a bit of distance but gained control. The most persistent mistake he fights is rotating his lower body too quickly on the downswing, getting the club “stuck” behind him. Unlike at any time in his life, he is in a maintenance mode, a difficult time for someone seeking constant improvement.

Killer instinct: No one ever questioned Jack Nicklaus’ killer instinct. Likewise, he was aware of his power

of intimidation. Other players thought they had to stretch beyond their abilities. “They really didn’t,” he says, “but they believed that.” As much as winning, Woods plays to crush his opponents’ competitive will. Such was the effect of Woods’ double-digit margins of victory at Augusta and Pebble Beach.

“He wants to stomp your heart out,” Hubert Green says. “Jack just wanted to win. Tiger likes to rub it in.”

Nicklaus didn’t. After Trevino skipped the 1971 Masters, Nicklaus told him he wasn’t doing his talent justice.

“What Jack said to me turned me around, and it didn’t do him any good,” Trevino says. “He didn’t have to do it, but that’s the kind of champion he is.” In contrast to the way Woods avoided playing with Mickelson at this year’s World Cup, Nicklaus at the 1973 World Cup afforded Miller the biggest confidence injection of his career. “Because Jack let me see him close up and was so open talking about the game, he made himself human for me, to the point where I began to believe I could beat him,” Miller says. “What’s amazing is that he wanted me to feel that way.”

Woods keeps his distance from those who dare to openly challenge him – Mickelson and Sergio Garcia in particular. “Just because I’ve become friends with more guys now doesn’t mean I have a hard time trying to kick their butts,” he says. “It actually makes having the killer instinct easier because that’s what professional athletes do. It’s not personal.”

Heroics: It’s true that Woods lives in an ESPN highlight world, but there is no doubt that in the biggest moments he raises himself like no golfer before him. Woods says such moments occur because of, not despite, the pressure. “Your senses are heightened when you’re in a clutch situation,” he says. “You just feel if you believe in something so hard, if you truly believe… the ball will go in.” What is left unsaid is Woods’ pure relish at the opportunity to demonstrate the full extent of his talent.

“Basically, he’s showing off,” Earl Woods says. “With Tiger, when he’s in a serious situation, it’s playtime, in his mind. He’s rare.”

Awe factor: Nicklaus’ domination over his peers inspired some of the game’s wittiest hosannas. Chi Chi Rodriguez called him “a legend in his spare time”. J.C. Snead said, “He knew he was gonna beat you, you knew he was gonna beat you, and he knew you knew he was gonna beat you.”

Still, Woods engenders even more awe from his contemporaries. “I knew Jack was better, but that I could beat him sometimes,” Green says. “These guys don’t think they can beat Tiger.”

Jeff Sluman provides one clue from earlier this year: “We were all watching in the locker room during the restart of the second round at Hazeltine when he hit that shot stiff with the 4-iron from a downhill, sidehill lie in the fairway bunker over the trees into a 30-mile-an-hour wind. There’s no man ever in the world who could hit that shot. Everybody just started laughing.”

Rodriguez says, “I was a better sand player than Jack or Arnold, a better long-iron player than Trevino, I hit the ball longer than Gary Player. But I can’t think of a single thing that I could beat Tiger Woods at, and that’s scary.”

Sense of destiny: For all his natural gifts and happy turns his life has taken, Nicklaus has always portrayed himself as down to earth, uncomplicated and exceedingly normal. “I’m a lucky guy,”

is about as far as he goes to explain how it all happened.

“It never ever entered my mind that there was any such thing as destiny,” Nicklaus says. “The only thing that was in my mind was that I had a Major championship to prepare for, and if

I wanted to win it, I better prepare.”

Woods, in contrast, has always carried his specialness as a given. He was raised to believe that the forces in his life are, in his father’s words, “a directed scenario”.

Such a life view has given Woods an inner calm and perhaps necessary arrogance. Although some of his personality traits might be considered flaws – he freely admits that he can be cheap, stubborn and cold – he seems to accept them as necessary tools for the life he is destined to lead.

“In a strange way,” says Bob Murphy, “I feel that Tiger is more confident than Jack was.”

Race: The most obvious difference between Woods and Nicklaus is that Woods is an ethnic minority. It’s also the most difficult difference to measure.

Tiger’s mother, Kultida, tells of early days at junior tournaments when he usually was the only non-white competitor. “He felt all the people’s eyes on him because he was different, and it made him uncomfortable,” she says. “I told him, ‘Tiger, you can’t tell them how to feel about you. But you can beat them. Win the tournament. Use your clubs, not your mouth. Use that rule, babe’.”

As Woods has become more famous, the subject of race has become more complicated for him to address. When asked how much his racial background has remained a source of motivation, his words lack an edge.

“I think it did as a kid,” he says. “I’ve always known I could play, but some people wouldn’t allow me to play or didn’t want me to play. That certainly provided extra incentive.”

Adds tour player Grant Waite: “I’ve wondered where Tiger gets his intensity, that feeling he gives off that he is on a mission, that he’s playing for something more than the rest of us. When I watch the Williams sisters play tennis, I wonder the same thing. I have to think it has a great deal to do with race.”

And then golf happened: 2004

For the legions conditioned to believe that Tiger Woods was invincible, 2004 was as surreal as the 81 he shot at Muirfield to end his 2002 Grand Slam bid and start his ongoing 0-for-10 streak in Majors.

On the heels of a relatively disappointing 2003, the numbers that had always substantiated Woods as the game’s best player no longer added up:

• Woods was supplanted by Vijay Singh as the No.1 player in the world (and even was briefly passed by Ernie Els for No.2).

• He had his worst year in the Majors (with his best finish a tie for ninth in the Open Championship).

• Woods tied career lows for full-season victory totals (one) and position on the PGA Tour moneylist (fourth).

• He hit new depths with his percentages for driving accuracy (56.1, to rank 182nd on tour) and greens in regulation (66.9, tied for 47th).

• Fittingly, he ended the official season by failing for the first time in his past 12 tries to win after holding a third-round lead.

As Woods slipped, the once-visible summit of Mount Nicklaus seemed to fade in the foggy distance. An insidious thought crossed the game’s collective mind: is the Tiger Era over?

So cataclysmic seemed the struggle that theorists looked for causes in life issues: marriage, his father’s health, burnout, injury, even ennui.

Woods probably hoped the second-guessing would be diffused when he gradually acknowledged the process of a swing change, one that had its beginnings in 2003 when he left Butch Harmon but started in earnest when he took on Hank Haney as an instructor in March 2004. Instead, the disclosure of changing the swing begged the question: why the heck would he do that? How could the player who from 1999 to 2002 had produced arguably the greatest golf ever played want to change his swing? It was like Michelangelo going back to chisel a more impressive six-pack on David.

Woods, who turns 29 on December 30, maintained that the changes weren’t as extensive as the ones he undertook from 1997-’98, calling them “refinement”. But as the year went on and he finished 33 strokes behind Phil Mickelson in the Majors, and as the misses to the right piled up, it became clear Woods had undertaken a formidable task. Still his standard reaction to his apparent swing quagmire was always this: “I’m close”. The stoicism spurred all sorts of random analysis, from Johnny Miller insisting Woods needed to forgo a draw for a fade to Singh opining that Woods hadn’t made necessary swing adjustments to accommodate his maturing body. Meanwhile, Harmon accused Woods of being “in denial”. In self-defence, Woods clung grimly to his achievement of 133 consecutive cuts made, something like Robert DeNiro as a battered Jake LaMotta proclaiming to a victorious Sugar Ray Robinson, “You didn’t knock me down, Ray”.

Finally, with his clubs for once not doing the talking, Woods was compelled at the season-ending Tour Championship to open up for the first time about his work with Haney and explain why he was changing. What emerged was the Tiger creed: I improve, therefore I am.

“I felt like I could get better,” he says. “People thought it was asinine for me to change my swing after I won the Masters by 12 shots… Why would you want to change that? Well, I thought I could become better.

“If I play my best, I’m tough to beat. I’d like to play my best more frequently, and that’s the idea. That’s why you make changes. I thought I could become more consistent and play at a higher level more often… I’ve always taken risks to try to become a better golfer, and that’s one of the things that has gotten me this far.”

Without Rival: 2006

Tiger Woods – living icon – is back. He had stood on that narrowest of pinnacles back in 2000 and 2001 before slipping off for a few years in pursuit of technical perfection. But by finishing 2006 with a rush towards the epic landmarks of Jack Nicklaus, Sam Snead and Byron Nelson while rising ever higher above his contemporaries, Woods enters 2007 loaded for history. He carries a streak of six straight official victories – the second time he has achieved the second-longest tour string of wins – but this time with a more palpable sense that Nelson’s 11 straight is attainable.

Only tennis’ Roger Federer among athletes today can rival Woods in dominating and personifying his sport. But whereas Federer confessed he became nervous when Woods showed up last September to watch him in the final of the US Open, it’s impossible to envision Woods being nervous in front of Federer, or anybody else. He’s simply too wrapped up in a higher calling.

“No one’s ever conquered the game of golf,” sums up his friend Michael Jordan, the one living sports icon who knows the same rare air as Woods. “He thinks he can conquer it.”

Woods arguably came closer than ever in 2006. He played in his last official tournament of the year, the WGC–American Express outside London, and won by eight shots for his eighth victory of the season. Then, drained from the emotional year of his father’s passing and a late run that included a dispiriting Ryder Cup, Woods passed on playing the eight more official rounds he needed to win his seventh Vardon Trophy scoring title and instead took his mountain of chips off the table and walked away. It left his opponents to think about what awaits them in 2007 and beyond.

“I’m sure Tiger will keep getting better,” says US Open winner Geoff Ogilvy. “It really doesn’t matter what he’s working on in his swing or whatever. It just distracts us from the fact that he’s always been the best. The level he achieved in 2000 was ridiculous, and after he won at Bethpage in 2002, he must have thought, What am I going to work on now? Tiger needs to have a project; he needs to have a mission. And his mission now is mastering his latest changes. He’s doing that, and he’ll probably win 10 times in the next year. Then he’ll find a new mission.”

For Woods’ main challengers, it’s all getting to be too much. The four players who have posed the greatest threat to his supremacy in the past four years – Phil Mickelson, Vijay Singh, Ernie Els and Retief Goosen – came at him with their best golf. All had success while Woods was struggling with swing changes, but when Woods started winning Majors again in 2005, all but Mickelson seemed spent. The gap only got wider in 2006 when he achieved the largest proportional lead by the No.1 player in the 21-year history of the Official World Golf Ranking.

Agony & Ecstasy: 2008

The week before the 2008 US Open, it was difficult for Woods to hit more than two practice shots without having to sit down. Still, he was steadfast about playing at Torrey Pines, the site

of his Junior World and Buick Invitational victories.

“I’d never seen him talk about a tournament so much before it started than he did about Torrey Pines,” says caddie Steve Williams.

Woods also talked when he got there, buoying himself by repeating two self-fashioned declarations.

The first was to Dr Keith Kleven, who was charged with managing Woods’ increasing pain. “It was probably the toughest week I’ve ever had in any sport, and the most relieved I’ve ever felt about anything when it was finally over,” says Kleven, who was in heavyweight champion Larry Holmes’ camp for several title defences. “Between stimulation and ice and some different systems that I use, you could block the pain, but you can’t block it for the whole day. It would come back during the round, and all the bending over and grimacing he was doing, that was the pain response to bone-to-bone and him doing whatever he had to do to get through it. Endorphins kicking in from the emotional part of competition probably kept him from feeling as much pain as a person would normally feel, but by the time he got back to the room he was wrung out and just wanted to lie down. We’d do several sessions from dinnertime to 11 or 12 at night, and then again in the morning before he played. We really didn’t know how much damage he was doing inside. I would ask him, ‘Are you sure, Tiger? Because we can’t lose your knee’, or I’d say, ‘I don’t know if we can go’. And he’d react like a boxer in the corner: ‘No, we can go, Keith, we can go. We can do this’. But most of the time he’d just come in and say, ‘I hurt it; you fix it’. He said that over and over.”

Woods’ other mantra was saved for the golf course. “Tiger kept repeating this one sentence,” Williams says. “He’d say, ‘Stevie, I’m going to win this tournament; I don’t give a s–t what you say’. He’d say it after a good shot, or a bad hole, or just to keep things light. It was a way to reassert his belief and just keep going.”

Woods needed an extra helping of will to overcome four double-bogeys (three of them on the first hole). “Really, there is no way I should have won,” he says, shaking his head. “Do I think about that a lot? Yeah… Yes.”

Woods had to rely on his team like never before at Torrey, and the timeliest help of all came from Williams. The man who will be remembered as the finest caddie of all time made what he considers his greatest call on the 72nd. Needing a birdie 4 to tie, Woods faced a 101-yard third shot from deep rough to a front-right flag on a firm green also protected by water. Williams paid attention to details but trusted an instinct honed during stints with Hall of Famers Peter Thomson, Greg Norman and Raymond Floyd.

“There was a lot of talk between us, and I managed to sway Tiger to the [60-degree] lob wedge, which he normally doesn’t hit more than 85 yards,” Williams says. “The shot that he had in mind, using a 56 to bounce the ball up without much spin, I just couldn’t see. There was a steep bank in front of the green that kicked everything hard left. With that shot, if you dropped 20 balls you could get the ball close maybe once.

“I knew he was pumped up, and I knew we were coming out of that tight kikuyu grass that still had some dew on it even though it was late in the afternoon because that side of the 18th stays in the shadow of the hotel. I knew that the moisture would help him hit it farther. I just had a feeling. I could envision him hitting that club as hard as he could and being able to get that distance out of it, with enough spin to stop it. Of course, if it didn’t come off, it was going to be a very long nine months. But it turned out perfect.”

Well, 12 feet away. His recounting of that bumpy putt offers a window into how Woods’ mind works under pressure:

“I was reading the putt, a ball-and-a-half outside right, thinking, You can’t control the bounces; all you can control is making a pure stroke. Go ahead and release the blade, and just make a pure stroke. If it bounces offline, so be it, you lose the US Open. If it goes in, that’s even better. I hit the putt, it felt pure, and I hit it just right where I wanted to. It’s rolling down there, I’m just, Break… please, break… break… not breaking… and then it started to barely move left, and at the very end it just dove. And as it dove, it caught the right edge of the lip and went in, and you saw me with some stupid reaction.”

Woods had to make another birdie putt on 18 the next day – a slick four-footer – to send the tournament against Rocco Mediate to the 91st and final hole, where Tiger won with a par. The entirety of the accomplishment makes Woods reflective of his early years.

“I grew up with a whole bunch of different military people – highly motivated people, and great people to be around,” he says. “I grew up with a Marine, with a Navy captain, a Navy admiral. A couple of the guys were in the Army infantry, and my dad was Special Forces. So this is what I saw. I saw the discipline side of it. I saw how to handle things. Whatever it is, you get the job done. Like my dad would explain to me, ‘Just because someone gets shot doesn’t mean he’s not effective. He can still operate. And just because you hit a bad shot doesn’t mean your whole round is over. You can still turn it around. You can still operate. You can still get it done’.”

As Woods does whenever he tries to make sense of his knack for great shots when he needs them most, his thoughts go back to seminal playing lessons with Earl Woods. “How do you explain to a 4-year-old not to have negative thoughts?” Woods asks. “My dad would say, ‘Where’s the trouble?’ I’d see water left and bunker right. ‘OK, where do you want the ball to go?’ ‘I want it to go there, Daddy’. ‘OK. What kind of shot do you want to hit?’ ‘I’m hitting a low draw’. ‘OK, do it’. And I’d put the ball right there. And he’d say, ‘OK, good’. And that’s the way I grew up playing. So it’s hard for me to explain negative processing. Even to this day, when I’m out there struggling, and I don’t have my best stuff at all, I’ll go back to, ‘You know what, Daddy, I’m going to put the ball right there. Right there. I’m going to put that little 2-iron right there, Daddy. No problem. I got it’. Boom, I put it right there.”

A public scandal: 2010

Woods’ old mystique – that of the chilly Chosen One immune to human weakness – is gone. It might well be that his former domination or even his competitive desire goes with it. Still, he has a chance to attain something more human. When he re-emerges, Woods will have truly suffered. Not knee-injury suffering, not even loss-of-father suffering. Rather the kind of suffering those heroes who have ruined their charmed lives confront at the climax of Shakespearean tragedy.

Just as it isn’t an overstatement to see the fallen Woods in such a context, so it is difficult to understate the potential scale of his redemption. Through all his folly, Woods has made passing Nicklaus’ Major record an even greater feat than it would have been without it. Because the ultimate measure of a man is not what he achieves, it’s what he overcomes.

Woods became golf’s Atlas, carrying everything – the PGA Tour, his near-flawless image as a role model, his foundation, his family, heck, the game itself – on his shoulders, all on top of the unceasing pressure to perform.

But as much as he sought glory, he resented the obligations that came with it, even if they made him incredibly rich. I remember Earl telling me that once he had tried to commiserate with his overwrought son by saying, “I understand how you feel”.

But, Earl recalled, “Tiger turned on me and said, ‘No, you don’t. You have no idea how I feel’. And I realised that I had underestimated.”

As Tiger’s life in his 30s became more tangled, he turned more inward. His inner circle got smaller and tighter, and those who overstepped or didn’t fit in were jettisoned. The best advice for those who are around Woods remains, “Don’t get too close”.

Those who were the closest saw the pressures and the toll. Out of sympathy, and the fact that he is their employer, they didn’t call Woods on imperfect behaviour like swearing, banging clubs and blowing by autograph lines. Within his camp, Tiger in a bad mood would be characterised in golf jargon: “Unplayable”.

Putting aside questions of infidelity, what’s intriguing is why Woods – always so calculating, detail-oriented and careful – was so reckless. With so much to lose, how could he be heedless enough to leave an e-mail, voicemail and text-message trail to tabloid hell?

“It’s not uncommon for an adult son, after losing his father, to be particularly susceptible to reckless behaviour,” says Neil Chethik, author of the book Father Loss. “The spectre of death and mortality can leave a man feeling that you only go around once, and so how do you enjoy it the most? Men can give in to whatever excess they are most vulnerable to. It could be drinking or gambling or sex. It’s more complicated for a megastar like Tiger because he can’t really have a normal private life. Everything is so exposed. He can really only have a secret life.”

It is also possible that on a deep level, Woods simply wanted out of an unsustainable life. As an architect of his destruction, his efficiency was on par with how he navigates a golf course.

If Woods was motivated by a self-destructive urge, he got more than he bargained for. The confluence of 24-hour cable news, blogs, websites and tabloids gave the information an immediacy and salaciousness that was depressingly irresistible. The details and the tone were so merciless that late-night comics felt tacit permission to pile on. Just like that, Woods had gone from one of the most revered and socially significant athletes in history to the most ridiculed.

It doesn’t matter that Woods has never been comfortable on the pedestal of moral superiority. It doesn’t matter that philandering has been part of pro golf since the Scots were stuffing featheries, or that it’s pervasive in other sports. Woods was supposed to be the guy with the superhuman discipline to withstand temptation, the example that millions of parents held up to their children, our vicarious thrill ride to the outer limits of human potential. We had presumed him, above all others, to be special. Betraying all that exacted a commensurate public disgrace.

No quit: 2016

So many key indicators suggest his career might be over: three recent back surgeries/procedures, recurring chip yips, scores in the 80s, WDs, the quiet desperation in a muttered “C’mon, Tiger” before hitting a third straight pitch shot into the water.

In the history of golf, no great player who has fallen from the top for this long has ever returned to dominance. No dominant player has ever dropped so far as quickly – from a record 683 weeks at world No.1 (for periods from June 1997 to May 2014) to No.683 in August 2016 – as Tiger Woods.

The shock is still being absorbed. If the Woods era has truly ended, it will have happened at an age younger than any all-time player since Bobby Jones. Woods won his 14th Major in 2008 at 32, but Jones’ retirement from competition at 28 in 1930, like Byron Nelson’s at 34 in 1946, was voluntary.

After looking as if he might have returned to his previous level after a 2013 in which he had five victories and won Player-of-the-Year honours, Woods has cratered. In the six Major championships he has played since then – he didn’t enter any of the four this year – he has missed four cuts. In the 64 he entered as a pro before that, he missed three.

The stark futility causes the mind to rebel. He’s Tiger Woods, the most talented, grittiest big-moment player ever. He can’t go out this way. “He’s done everything else,” says Dr Jim Afremow, sport psychologist and author of The Champion’s Comeback, a study of the components and behaviours in the successful return of great athletes.

“Coming back in a way that matches those other things is the only thing he hasn’t done. It’s why we can’t stop talking about him.”

Improbable & familiar: 2019

On a frenetic masters Sunday in 2019, tiger woods held steady as others unravelled around him.

By Dave Kindred

Yes, as he had done in halcyon days when he owned the world, Tiger smoothed along when it mattered most. He let the lesser players find ways to damage themselves. This time, on holes 11 through 17, Woods went par-par-birdie-par-birdie-birdie-par and, when it no longer mattered, a bogey at the 18th where, after the last little putt, he allowed himself, for the first time all day, a moment of celebration. He threw high and wide his arms to the thousands of fans, jubilant and raucous, the air ringing with “Tiger! Tiger!” Coming off the green, he embraced his mother, Tida, and his children, Sam and Charlie, before moving through a handshake line of players celebrating their old hero reborn, Brooks Koepka, Justin Thomas, Bubba Watson, Mike Weir, Zach Johnson.

Six months ago, Woods said, he began preparing for this Masters.

So, is the Nicklaus record on his mind?

Not now, he said. Not on this great day.

“I’m sure that I’ll probably think about it going down the road.”

The old dad, 43, was happier thinking about Sam, 11, and Charlie, 10.

“For them to be here and see what it’s like to have their dad win a Major championship, I hope that’s something they’ll never forget.”

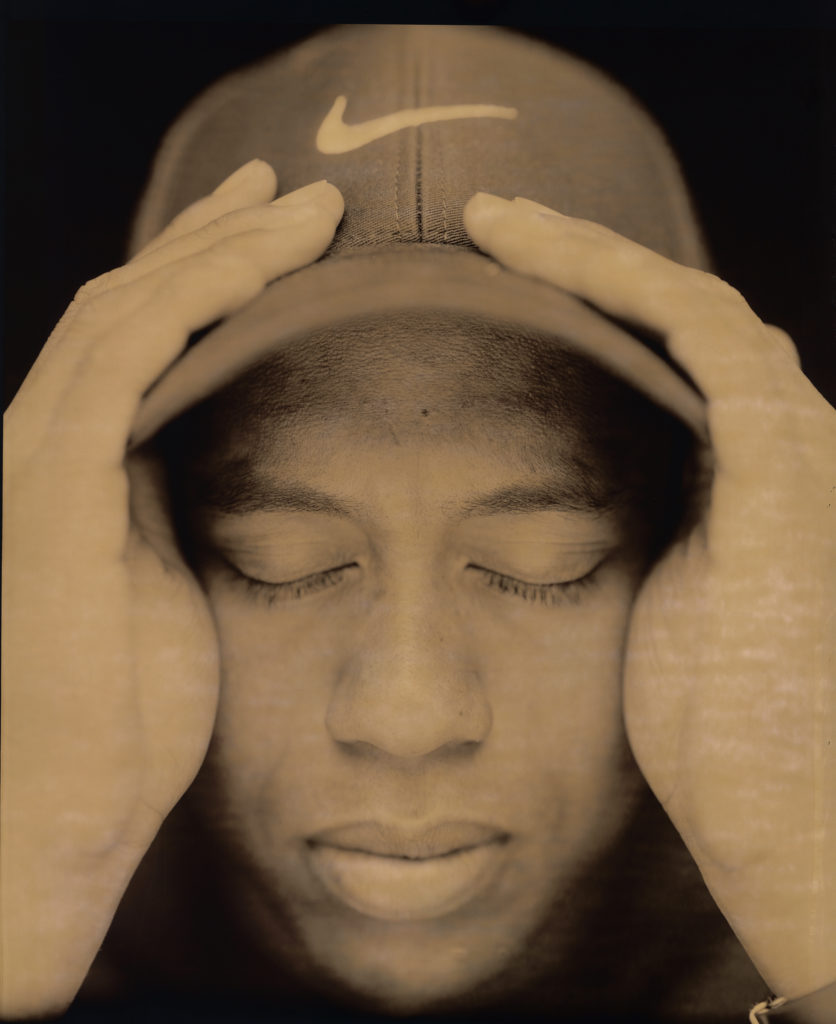

Feature image: Rob Tringali/Sport chrome/Getty images