ON a big screen inside a big tent at Bay Hill, at the first Arnold Palmer Invitational since the great man’s death, MasterCard debuted its new commercial. One topical vignette in the ad portrayed Ian Poulter and Graeme McDowell wading into a crowd of excited kids holding up pens. Poulter We’re gonna sign everything. McDowell Arnie would. Poulter Arnie definitely would. McDowell Yes, he would.

Damn right he would. Palmer’s forbearance and endurance with autograph seekers was among the many qualities that made him golf’s de facto patriarch and PR MVP. This same day they unveiled another tribute in the plaza near the first tee, a 13-foot statue of The King apparently hitting a pull-hook. A metal Arnold signing programs with perfect penmanship wouldn’t have been as dramatic a pose, but it would have been just as true to his legend.

Depending on who’s talking, the annual worldwide

collectibles market could be approaching $400 billion.

Sixty steps from the sculpture of the patron saint of autographs, a cadre of professional signature seekers huddled by the white picket fence bordering the putting green. There were eight of them, each clutching a clear plastic shopping bag stuffed with … stuff. How they dress is their other tell – more L.L. Bean than J.Lindeberg – but this group of mostly middle-age men effected at least a muny-course look: golf shirts with the tails out, khaki-coloured cargo shorts and sensibly priced athletic shoes. They stood still and silent in the cool blue morning, as patient and motionless as birds waiting for worms. On the other side of the fence, two dozen of the world’s greatest golfers chipped, pitched and putted.

“What do you think of those guys with the bags?” I asked various of the world’s greatest. “What do you think of what Jordan said?”

A month before, at the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am, Spieth had gone to the ropes to meet the people, especially the kids, as he usually does after a practice round. It didn’t go well. He was still a little steamed during his post-round presser.

Q “I know you sign a lot of autographs, but coming off 18 today some guys ragged on you pretty hard for not signing … and it got a little testy?”

A “Yeah … these guys that just have bags of stuff to benefit from other people’s success when they didn’t do anything themselves. Go get a job instead of trying to make money off of the stuff that we have been able to do. … They frustrate us. And so I turned around and they, one of them, dropped an f-bomb in front of three kids, so I felt the need to turn around and tell them that wasn’t right. And a couple of them were saying, ‘You’re not Tiger Woods; don’t act like you’re Tiger.’ … Normally I let Michael [Greller, his caddie] get into it with them … Scums … It just bothered me.” (Added Spieth later in the week: “I shouldn’t have used that word, but I was a bit frustrated.”)

“Some of the players are really proud of Jordan for standing up like that,” said Keegan Bradley.

“I couldn’t agree with him more,” said Cody Gribble.

“They can be intimidating,” said Geoff Ogilvy. “They tend to be pushy. It’s pretty full-on. You see a man’s arm coming at you from between kids. Although I didn’t mind signing about a thousand Golf World covers after I won the US Open.”

Henrik Stenson evinced the minority, laissez-faire attitude about the autograph pros: “I’m providing for them, too. So I keep on signing.”

We found only one other player who agreed with Henrik, and that was the infinitely patient and recently deceased Palmer.

“Someone would hand him 10 of something, and he’d sign all 10,” says Alastair Johnston, Palmer’s longtime agent, with a sigh and a laugh. “I’d ask him why. He’d say, ‘Well, these guys have to make a living, too.’”

The autograph scene on tour presents a dilemma with many confusing aspects: the players are quite aware that willingness to put one’s name on things over and over again is the very definition of good-guy-ness. Arnie would, until the cows came home: great guy. (Ditto Phil, Rickie and, yes, Jordan.) During their competitive years, Hogan and Woods most often couldn’t be bothered.

But Ben and Tiger didn’t have to autograph your program; no one has to. The tour does not compel players to sign, nor are tour events required to provide a place for them to do so. A golf star can just walk on by, or sign for kids only. When Brooks Koepka did exactly that, and an adult collector kvetched, “Why not mine?” Koepka replied, “Because I’m not making your money today.”

But the kids-only policy isn’t that simple, for some teens and tweens are also in it for the money and offer their signed flags online as fast – probably faster – than any adult. And though there are occasional unseemly battles, such as the war by the shore at Pebble, every ardent collector agrees that golfers are the best of all athletes: the most affable, the most willing and the easiest to get to, especially when compared to baseball players.

“Manny Ramirez,” one Orlando bagman said.

We looked to Annika Sorenstam for some clarity. She sat at a table beneath the bronze Arnie and affixed her name to this and that. Her policy, she says, is to sign anything – even a competing brand of golf ball, even before a tournament round. But only one per customer, please: after the autograph pros got theirs, she quietly told an assistant to make sure they didn’t get back in the queue for another.

Inside The Scrum

A man and his two daughters stood nearby, sneaking peeps at Annika. On holiday from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, visiting his dad, said Travis Nadeau. This year at Bay Hill, and regularly at the Dell Technologies Championship outside Boston, the adorable and golf-smitten Nadeau kids collect autographs for their girl caves back home; a ball signed by Danny Lee is a prized possession. “He wrote, ‘To my best friend’ on it, said Teagan, 8.

What about the grown men competing for Danny Lee’s attention – any problems with them?

“They follow us,” said Delaney, 10. “Then they move in front of us.” Travis shook his head sadly.

Ignoring the rules of personal space and taking turns. Shoving. Using outdoor voices in golf’s churchy setting. Inducing children to get signatures for them, making it impossible not to be reminded of Fagin and Oliver Twist; and now, profanely insulting one of the most popular sportsmen in the world.

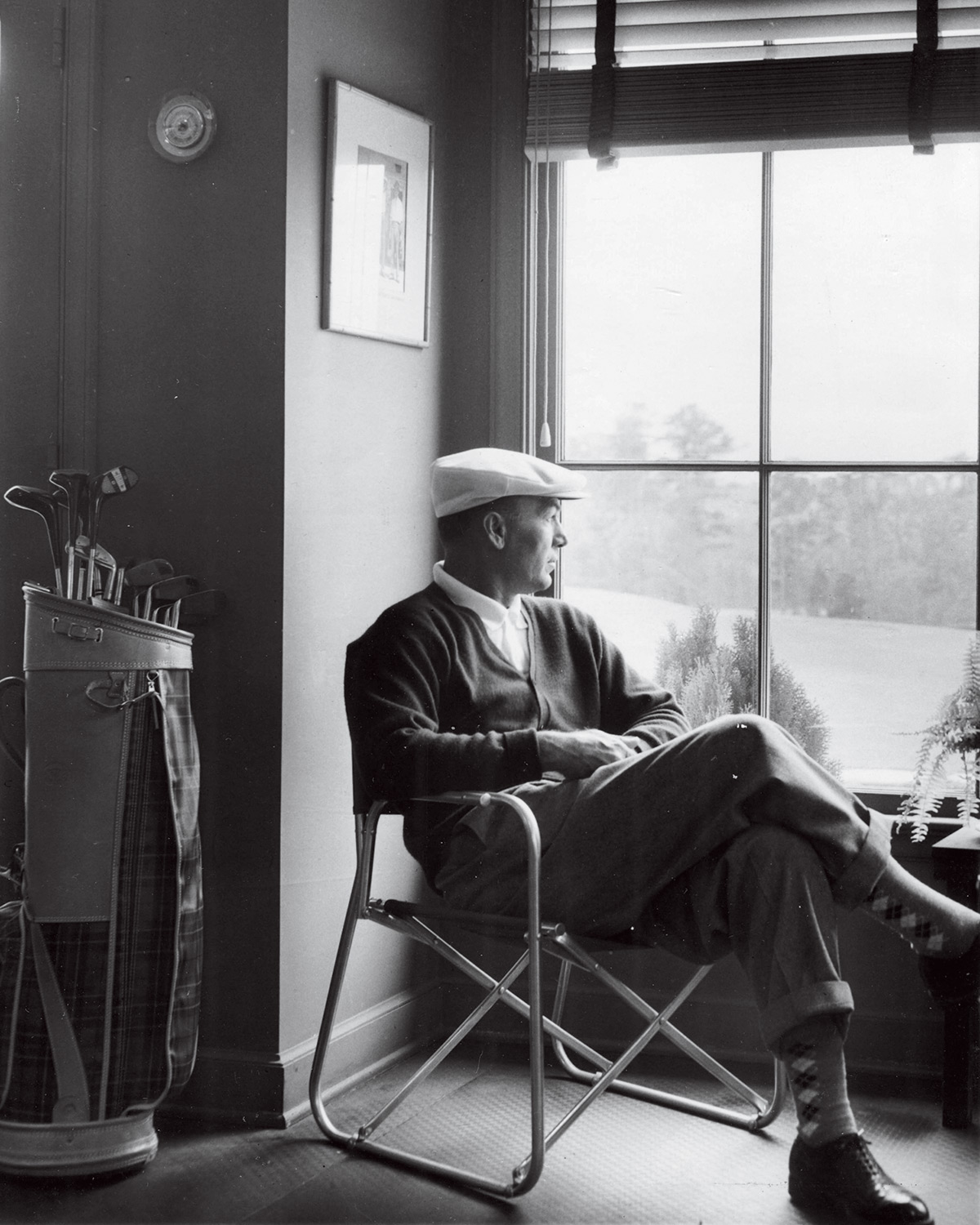

But decorum ruled when AP went to the ropes, and “Please” and “Thank you” filled the air, in part because The King signed everything for anyone. An estimated three million autographs in his lifetime. Legibly: big A, big P, and the 10 attached little letters were even and distinct; it’s no surprise or coincidence that Sam Saunders, Arnie’s grandson, has the clearest signature on tour. At home in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Palmer dutifully autographed items by the truckload, and returned to senders on his own dime. It cost him a fortune.

Palmer was dogmatic on the subject. As Peter Jacobsen recalled, Arnie would put down his glass of Ketel One on the rocks, twist of lemon, and instruct his young friend to always be nice. Don’t scribble your name, for God’s sake. Sign a golf ball if they want (which is a pain; try it). Don’t come off the 18th green mad; people don’t care if you just shot 60 or 80. And don’t disrespect the guy who is obviously going to sell your autograph.

Big Business, As In Billions

What has changed, we suppose, is that they made only one Arnold Palmer, and there is an increasing demand for things signed by golfers, and such items appreciate. Depending on who’s talking, the annual worldwide collectibles market could be approaching $400 billion, and the subset of autographed sports things, from football helmets to baseball bats to golf balls, is between $1 billion and $2 billion.“Now is the time to invest in Jordan Spieth memorabilia, the youngest player ever to dawn [sic] the Green Jacket,” asserts Sports Memorabilia (sportsmemorabilia.com), although Tiger actually had an earlier dawn. SM lists a 2015 Masters flag, signed by the champion in a cramped scrawl, at $1,463.99; the same item with “Jordan” written above “Spieth,” in a spacious hand: $4,363.99. Legibility is crucial to value.

The time had come to stand among the foot soldiers. Autograph chasers, as they are known in the biz, lack a collective noun: a desperation, perhaps? A scribble? For interminable minutes we observed Danny Willett’s wristy chipping style. When finally he made to leave the scene, one of us called out. “Danny, will you sign?”

He would. Two handfuls of amateur collectors had joined the group. During an orderly, wordless interaction, the high-strung Englishman hurriedly scratched black ink on 10 yellow nylon rectangles and on two tournament programs. His John Hancock consists of a giant D above a vertical chop that resembles a pictograph of a picket fence. Though prices fluctuate, we found a Masters flag signed by the 2016 champion for as little as $100 on eBay. From the actual sale price, deduct the cost of the cloth – about $25 – eBay’s 10-percent commission, shipping, the price of a ticket, clear plastic bags and cargo shorts, and no one was getting rich on Danny.

I introduced myself and my mission to the group. “Is that how this is done – eBay?”

Silence. They regarded me balefully, with weapons-grade stink eye.

“Is there enough money in this for you to travel from one tour stop to another?”

Silence. The desperation looked like eight untipped waitresses.

Then, from the tall one, “No comment.”

“No comment? Really? Is it because you fear a negative story? Well, the negative story is already out there. Maybe you can help me tell a positive … ”

“No comment.”

Then they all turned their backs, a full Amish shun, impressively synchronised. A little later, they moved en masse to the other side of the green, and they didn’t appear to enjoy my company there, either. They seemed like a team – and they probably were. Tampa-based dealer Charles Poulos, a still-occasional chaser, explained the usual MO: groups of two to five or larger will travel in the same van and stay in the same inexpensive hotel room. They pool expenses but not income. Their bags are filled with consigned flags, hats, trading cards and photographs waiting for the Midas touch of a golfer’s pen.

“I’ll get on a collectors’ website and ask, for example, ‘Who’s going to [the PGA Tour Champions event in] Branson?’” says Poulos, whose full-time job is in IT. “Someone will say, ‘I am. What do you need? What will you pay?’ And if I trust him, I’ll send a guy – usually, two guys – 20 or 30 items. I expect to get half or a third of what I want. It’s an incredibly tough life for those who do it full-time. They don’t make a lot. It’s discouraging when I see some guys bring their kids out [to secure autographs]. It’ll be the middle of the week, and I’ll think, Why aren’t these kids in school?”

Poulos, who is essentially a middleman, sells to five other dealers, one of whom is in the United Kingdom. The best stuff – for example, not just a run-of-the-mill Fred Couples-signed Masters pin flag, but one on which Freddie was induced to write “’92”, the year he won – is offered to the big hitter in the business, Green Jacket Auctions.

Green Jacket co-founder Bab Zafian, whose expertise is autograph authentication, wishes first of all to emphasise that chasers are the salt of the earth, hard-working Americans who rise at 5 and go to work. “Would Jordan Spieth go up to a janitor and insult him?” Zafian says. “Don’t look down on anyone. It’s a job, like anything else.”

But it’s not a job like anything else, and Zafian acknowledges that society sometimes breaks down by the yellow rope. He has been out there himself, many times. “When they’re pushing kids out of the way, I’ll say so everyone can hear, ‘Come on, let the kid in there!’ I’m not being fake. Once Jack Nicklaus saw my courtesy and made a point of signing for me.”

Compared to Poulos, Zafian offers a relatively rosy opinion regarding chaser income: “You’ll see a guy who looks homeless, someone you want to hand a dollar to; that guy could be making $100,000 a year. Even if they get only $10 per autograph, if they get 50 or 75 a day … ”

The group I watched for three days weren’t getting anything close to that.

Writers are chasers, too, of course, of stories – so here’s a defence of my brothers the Orlando Eight weren’t willing to provide. They fill a need. When they’re not rude, they’re polite. They’re determined. They are, as advertised, early risers. And they are organised; Vaughn Taylor has won three times on tour, but he’s no household name, so he was surprised when a collector recently asked for signatures on four Vaughn Taylor photographs beautifully printed on heavy stock. If Vaughn wins the US PGA Championship, or something, they’ll be worth something.

The Days Before There Were Autographs

When did so many urchins, scamps and rascals start turning up in the galleries of golf tournaments? That’s one question. Another is, when did they start clawing and begging for an autograph from any person who bore the slightest resemblance to a touring pro?

I distinctly remember a time when I was the only urchin, scamp or rascal in the galleries. It began when I was 11 years old and was taken by golf-nut relatives to Colonial Country Club and let loose on the 1941 US Open, where I got mad that Craig Wood won instead of Ben Hogan or Byron Nelson, the hometowners.

But I didn’t consider myself an urchin, scamp or rascal. I’d been playing golf since I was 8 and had learned that the game was a civilised, dignified sport. If anybody had hollered “You da man!” or “Get in the hole!” he’d have been arrested for disturbing the peace.

My education continued as follows:

As a 14-year-old, I was taken to Lakewood Country Club in Dallas to watch Byron Nelson win the Texas Victory Open.

As a 15-year-old, I took myself to Dallas Country Club in 1945 to watch Sam Snead win the Dallas Open.

Again in ’45, I went the entire 72 holes in Fort Worth, watching Byron win the Glen Garden Open, his 18th victory in that fanciful year.

Then in 1946, as a grown-up 16-year-old with a car, I watched Hogan win twice. First at the inaugural Colonial National Invitation in May, and again in September at the Dallas Invitational at Brook Hollow Golf Club.

I roll those credits for a couple of reasons.

It’s to say that in all of my exposure to tournament golf I never once saw an urchin, scamp, rascal or teenager on the course, including me, plead for a golf ball from a pro. And second, I never once saw an adult ask a competitor for an autograph.

It just wasn’t done back then. At least not in my neck of the woods.

Applause from the crowds was reserved for a very good golf shot. Most of the fans were recreational golfers and obviously more knowledgeable about the game than many in today’s throngs.

Also, there were no standing ovations for players you’ve never heard of simply because they walked up on a green.

“Come on Brendan, you can do it!”

Who?

What changed this peaceful world?

The usual suspects, is my guess. Hogan, to begin with. The game had needed a larger-than-life figure since Bobby Jones retired. Then TV. Followed by Arnold Palmer. The combination of TV and Arnold Palmer. Jack Nicklaus. The dynasty of Jack Nicklaus. More media attention to the Majors. Especially the Masters. Growth of new courses – a country club for every income level. Advances in equipment. Corporate sponsors and the incredible explosion of prizemoney. And, yes, a guy named Tiger Woods.

Full disclosure: in my teens, after watching all that tournament golf, I did have fleeting thoughts of trying to become a touring pro, but I quickly realised it required more practice than it did fun-filled gambling with friends and thieves, plus my game didn’t travel well.

So I changed my major.

– Dan Jenkins