Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, future pro-caddie-to-the-stars Cayce Kerr could have been like most kids, worshipping athletes or lead singers in rock bands. But Kerr showed at a young age that his mind worked quite a bit differently. It’s pretty much guaranteed that he was the only teen in his native Maryland who idolized Benjamin Franklin.

“The reason is, if you Google how many inventions he had, the number will blow your mind,” Kerr said recently in a phone conversation. “And I always felt like I could invent something, so he was my American hero. I can’t explain it to you, but I just see things, and I see them through all the way, and I just have vision.”

Kerr is correct on Franklin, of course. Beyond being one of the founders of the United States and signing the Declaration of Independence, he was a prolific inventor, with the lightning rod, swim fins, the Franklin stove and flexible urinary catheter counting among his works.

Kerr would acknowledge that he didn’t quite have the brainpower or means to be a once-in-century American figure, but his fertile mind never stops churning. Having caddied on the PGA Tour in five decades, toting the bags of 16 major champions—including Ernie Els, Vijay Singh, Fred Couples, Hubert Green and Fuzzy Zoeller—the 64-year-old has seen and done it all in the sport. Yet there is one example of his “vision” and entrepreneurial prowess that stands out above all others: Kerr introduced the now-ubiquitous rangefinder to professional golf, beginning a revolution that culminated with the PGA Tour experimenting for the first time this season with their use in competitive play.

Cayce Kerr caddieing for Fuzzy Zoeller in 1999.

PGA TOUR Archive

Looking to speed up play, the tour announced in March that it would allow rangefinders in six events between the Masters and PGA Championship, beginning with last week’s RBC Heritage. An eventual permanent acceptance would seem likely, since LPGA players are regularly allowed to use them, and the PGA of America OK’d their use in the PGA Championship starting in 2021.

“It was inevitable that they would approve it,” Kerr said. “It enhances the performance of the player, and it speeds up play.”

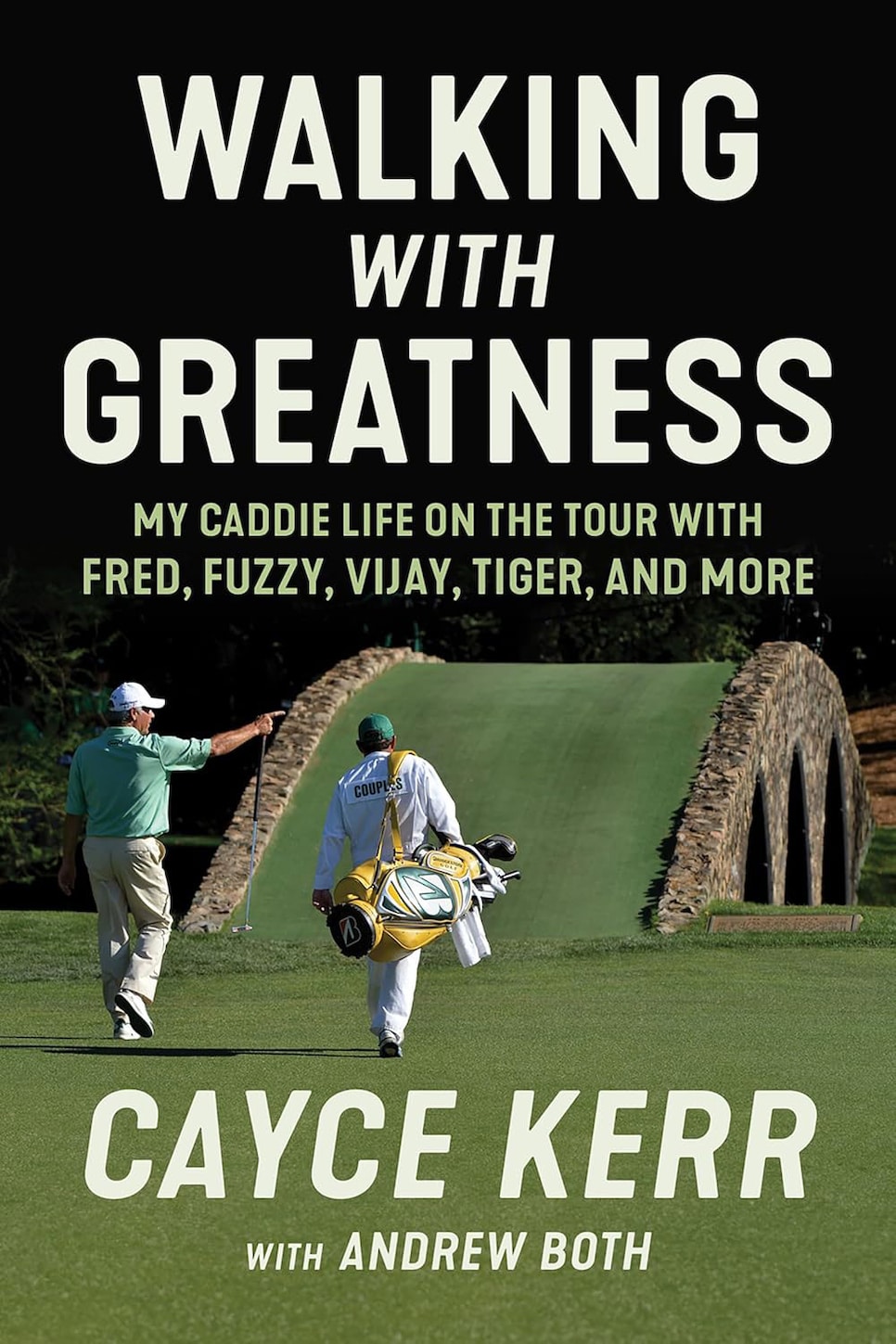

By happenstance, the timing of the PGA Tour’s rangefinder experiment coincided with the publishing this spring of Kerr’s book, Walking with Greatness, on which he collaborated with writer Andrew Both. As one of the tour’s all-time raconteurs, Kerr has plenty of insightful and funny stories to share about some of the game’s greatest players, and one of the best chapters is less about people and more about how Kerr’s own curiosity, ingenuity and hustle brought rangefinders to the fore in America.

“I was the first. I pinpointed it. I nailed it,” Kerr said on the phone.

As Kerr tells it, he was caddieing for Zoeller in 1995, and during a practice round for the U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills, the two-time major winner left himself a 3-wood approach to a green. Zoeller asked for the yardage and Kerr replied, “It’s everything you got.” Not happy with that response, Zoeller shot back, “Give me the goddamn number.” The two were close enough to the ropes for a couple of spectators to overhear the exchange, and one of the men called Kerr over to tell him he knew of a device that could read yardage. Kerr’s response was, basically, “Get the hell out of here,” but he took the man’s contact info anyway.

The knowledge of this device stewed with Kerr, and at the end of the ’95 season, he reached out to the guy he had met at Shinnecock to talk. The man worked for the Austrian company Swarovski, the glass and jewelry maker, renowned to this day, that was founded in 1895. Swarovski was adept at making optical glass for binoculars and was just beginning to roll out a new golf product that could read distances with one push of a button.

The company invited Kerr to its headquarters outside of Innsbruck, and he was immediately blown away. “They had a Rolls-Royce product, and I knew Rolls-Royce customers,” Kerr wrote in the book.

On a handshake, Kerr left Europe with a deal that he would have 12 months of exclusive U.S. rights to the sell the Swarovski rangefinders. He would get 350 of them for $1,000 apiece and could sell them for whatever the market would bear.

So Kerr arrived at the first tournament of 1996, the Tucson Open, with 10 rangefinders in the hopes of maybe selling five. His price tag: $3,300. It turned out that the demand was so immediate that he might as well have been peddling rights to the Fountain of Youth.

Scotsman Sandy Lyle was the first customer, quickly sold on it after Kerr showed him he could pinpoint a flag on the range from 232 yards—the perfect 3-iron for Lyle. “He bought it in less than 30 seconds,” Kerr mused.

Bob Tway was next, followed by the huge “get” of Arnold Palmer. The King’s purchase created a lot of locker-room buzz, and the sales took off from there, with more major champs, including Hale Irwin, Tom Watson, John Daly and Davis Love III, jumping on board. Greg Norman bought three.

There was one player, Kerr wrote, who tried to circumvent him for a rangefinder: Jack Nicklaus. Kerr said the Golden Bear tried to go directly to Swarovski, but the company gave him a firm “no” and said he had to deal with Kerr. Nicklaus eventually obliged, and it was a huge relief to Kerr, who didn’t want the players to know the big profit he was making.

The reason the rangefinders were a huge hit was simple: While players and caddies relied for centuries on stepping off yardages from fixed objects, sprinkler heads or faith in their own eyesight, the device took away any doubts. “Put it this way—it wasn’t a gimmick,” Kerr said. “Now you could have conviction in what you were seeing. Golfers don’t like ambiguity.”

One prime example Kerr gave that isn’t in the book is that he says for years players believed Augusta National Golf Club was not providing them the correct yardage for the famed par-3 12th hole. They just couldn’t fathom why their relatively short tee shots sailed long into the azaleas or came up well short in Rae’s Creek. Once the rangefinders arrived in ’96, they got their proof: Augusta’s stated yardage was right on and maybe the swirling winds were more of a factor than they thought. “The main thing is it removed any doubt,” Kerr said.

Rangefinders’ use in practice rounds became invaluable. Kerr would shoot yardages from basically anywhere he thought his players might possibly end up. Standing on the front of a green, he would look back down the fairway and laser the distances to trees. Any golfer can accomplish all of this now, but back then—nine years before Apple would debut its first iPhone—this shiny new and wondrous toy was game-changing.

By the end of that one-year sales contract in ’96, Kerr had sold all 350 rangefinders for a total profit of more than $800,000. He doesn’t mention it in his book, but Zoeller’s earnings in 16 events that season were $347,629. He’d more than doubled his boss’ salary.

‘They had a Rolls-Royce product, and I knew Rolls-Royce customers.’

—Cayce Kerr, on becoming the first distributor of rangefinders in the U.S.

Today, Kerr is mostly retired from caddieing and lives in San Antonio. He’s been battling rectal cancer for the past few years. “I’m taking each day as it comes,” he said. “I’ve had a great life.” But he’s also working on new ventures, including a company he co-founded, World Tour Survey, that does the player club surveys at LIV Golf events; this week he’s at LIV’s event in Mexico City.

On another front, Kerr has a new technology he’s worked on that he says has drawn interest from the USGA. Like any good inventor, the mind doesn’t rest. “I’ll tell you about it next time,” Kerr said at the end of the phone call. “It will blow your mind.”

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com