Welcome to MythBusters, a Golf Digest+ series where we explore answers to some of golf’s most common questions through a series of tests with real golfers. While our findings might fall short of definitive, they still aim to shed new light on topics that have consumed golfers for years.

On a typical drive, how hard do you swing? It’s often a subjective assessment, but it’s common for golfers to swing about 85 to 95 percent of their maximum effort.

But is that ideal? Would you shoot lower scores if you swung all out, using 100 percent of your energy on every drive? Or conversely, would you be better off if you made a fairway-finder swing with 70 percent effort? We tested it.

Our test

To learn more about how swing effort affects distance, accuracy and ultimately, your score, two Golf Digest staffers—Drew Powell (+2.4 Handicap Index) and Sam Weinman (11.4 Handicap Index)—hit 20 drives each with varying levels of effort.

MORE: Do layers of clothing slow down swing speed? Our test reveals surprising results

Each player hit 10 drives with 100 percent effort, where their only goal was to maximize distance with no regard for accuracy. Additionally, each hit 10 drives with a fairway-finder swing, where the only goal was hitting the ball as straight as possible. Powell and Weinman switched between each swing type after every shot, to account for energy levels.

We measured carry distance and dispersion, taking out the strongest outlier from each set before analyzing the data.

What we found

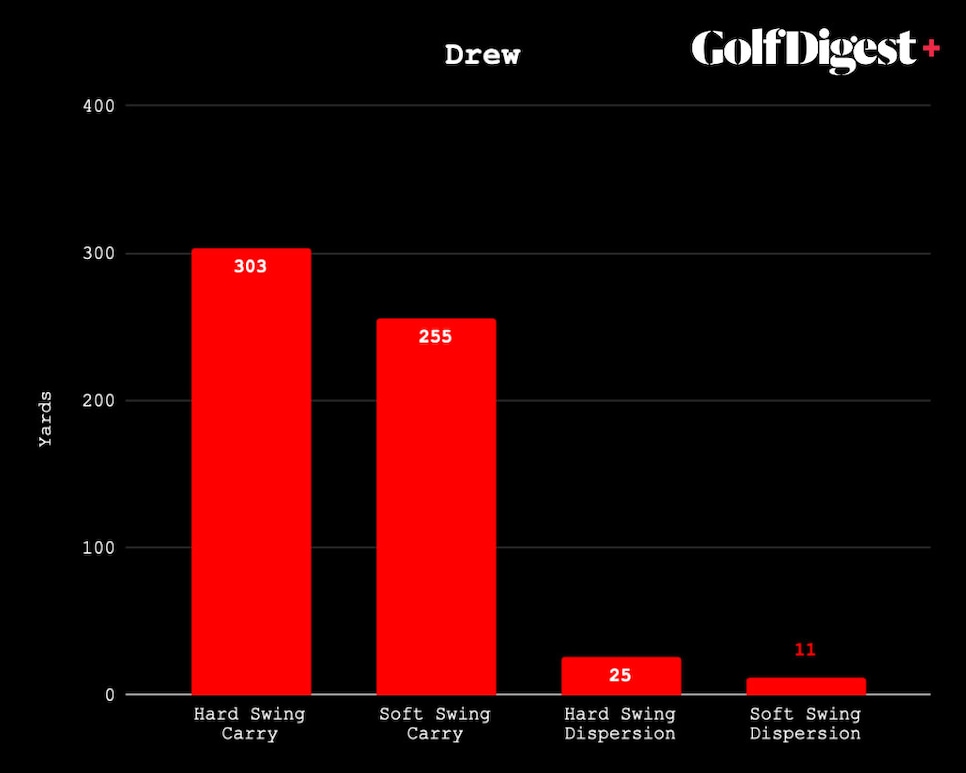

Powell’s average carry distance with his all-out swing was 303 yards, while his fairway-finder swing averaged just 255 yards through the air, 48 yards less. His dispersion, however, was much tighter with the easier swing, averaging 11 yards offline versus 25 yards offline with the hard swing.

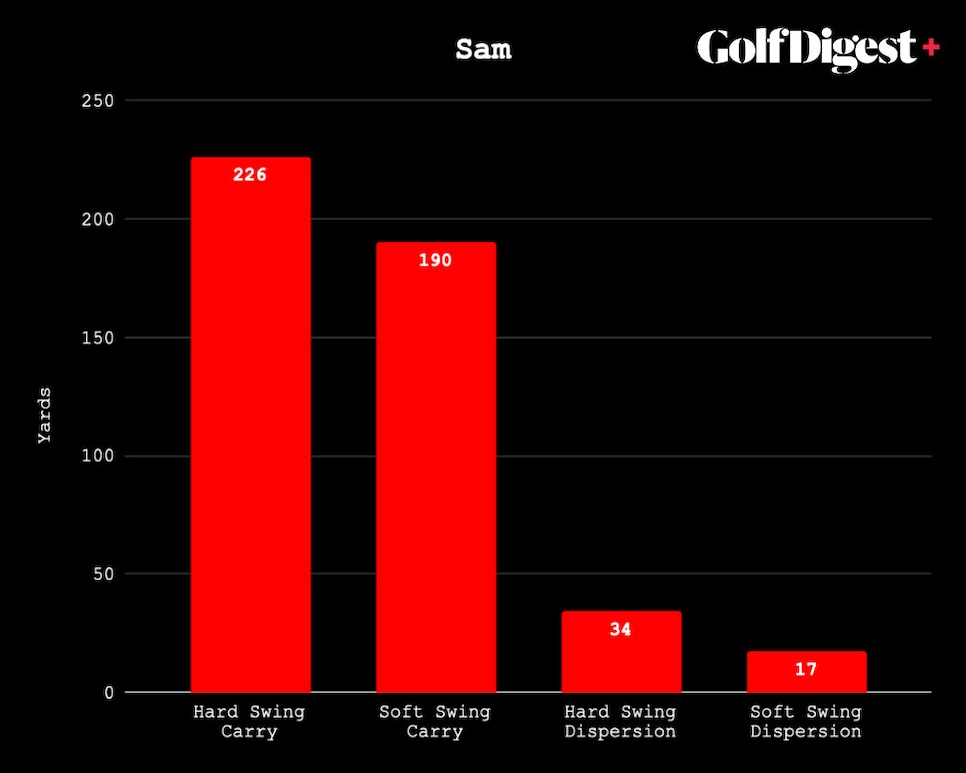

Weinman’s results were similar. His carry distance was 36 yards more with the hard swing (226 vs. 190), and he averaged 34 yards offline with the 100 percent swing and 17 yards offline with the smooth swing.

What does it mean

Of course, these results are not surprising, but to really understand how hard you should be swinging, we must consider the on-course trade-off of hitting it farther and less accurate versus shorter and straighter. Put simply, is it better to be closer to the hole in the rough or farther away in the fairway?

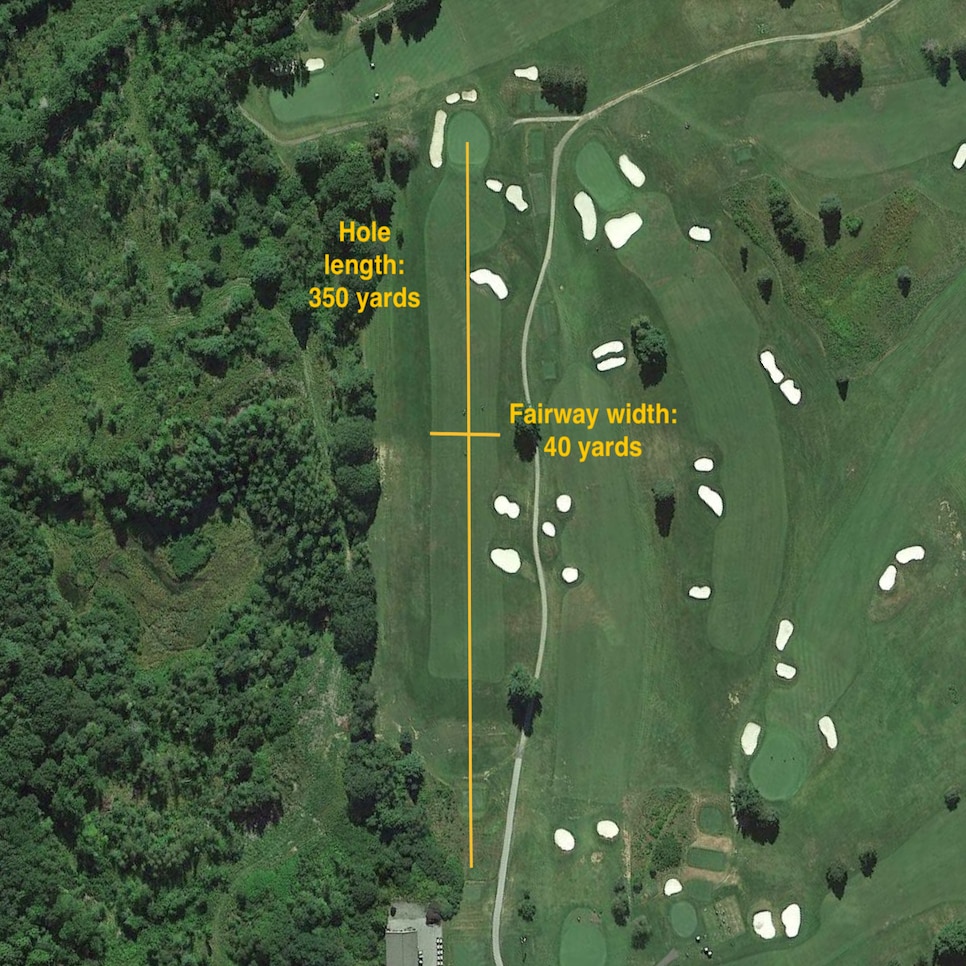

This is a complicated question with many variables including fairway width, rough length, penalty areas and more, but to provide some context, we overlayed our results onto a fairly straightforward hole.

Below is the first hole at the Donald Ross-designed Penobscot Valley Country Club in Orono, Maine. The hole plays about 350 yards and has a 40-yard-wide fairway.

On this hole, as an example, Powell would have averaged about 47 yards away with his approach shot (for simplicity, we assumed no roll-out) with his hard swings and 95 yards away with his soft swings. Given that his dispersion was much greater with the hard swings, we calculated that of the nine shots counted, seven would have missed the fairway, whereas just one would have missed the fairway with the soft swing. So, we placed Powell in the rough at 47 yards and in the fairway at 95 yards away.

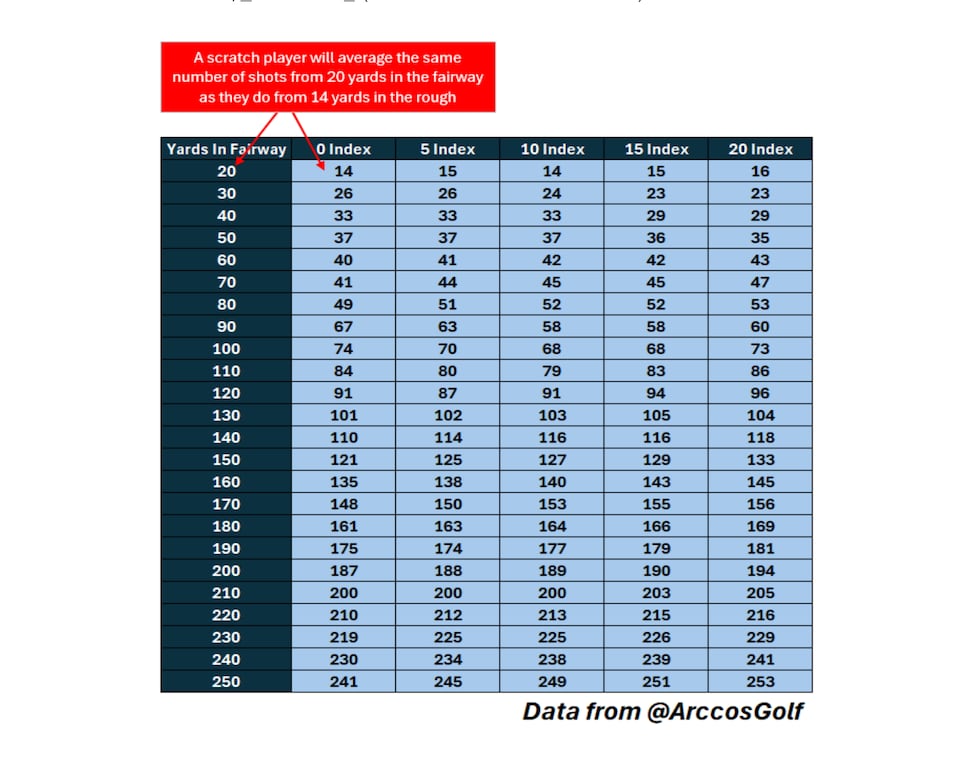

So, is it better to be 47 yards away in the rough or 95 yards away in the fairway? Luckily, Arccos stats guru Lou Stagner has a helpful chart that compares scoring averages from the rough versus the fairway at varying distances. The below is taken from his weekly newsletter, which is a fantastic read for stats nerds.

Using the chart, we see that for a scratch golfer like Powell, that player will average the same number of shots from 90 yards in the fairway as they will from … 67 yards in the rough.

Put most simply, for a scratch golfer, 90 yards in fairway = 67 yards in rough (in terms of scoring average).

Of course, the 47 yards that Powell has left in our example is significantly closer than 67 yards, so Powell will average fewer strokes from 47 yards away than he would from 90 yards in the fairway.

In other words, Powell is giving up too much distance by using his fairway-finder swing to make it worthwhile in this scenario.

MORE: Does taking more club actually help? What our test reveals

Next up, when we look at Weinman’s data, we calculate that he would have missed the fairway eight times with the hard swing and just three times with the soft swing. So, though it’s an assumption, we placed Weinman in the rough, 124 yards away for the hard swing and in the fairway 160 yards away for the easy swing.

Which is better? Back to the chart. Weinman is about a 10 handicap, so according to the stats, he will average the same score from 160 yards in the fairway that he will from 140 yards in the rough.

For a 10-handicap, 160 yards in the fairway = 140 yards in the rough (in terms of scoring average).

But in our example, Weinman only has 124 yards away in the rough when he takes his all-out swing, so he will average fewer strokes from there than he would from 160 yards in the fairway.

Like Powell, Weinman is giving up too much distance by using his fairway-finder swing and is better off swinging all-out in this scenario.

Yes, this is a limited example, but it provides insight into just how much (or little) being in the fairway matters for different levels of player. As you can see from Stagner’s chart, it is often worth giving up 5, 10 or even 20 yards to be in the fairway, but rarely, if ever, is it worth it to give up 30 or 40 yards, like Powell and Weinman were doing with their fairway finder swing.

What it doesn’t mean

There are a few assumptions we made in our example. First, we assumed that Powell and Weinman found the fairway with their easy swing and missed it with their hard swings. While the data show that this would be true the vast majority of the time, it is by no means a guarantee that an easy swing will go straight and a hard one will go crooked.

Perhaps your all-out swing will find the fairway, in which case you’re much better off than you would be with an easier swing.

Other factors come into play on various holes, such as rough length, fairway width, penalty areas and bunkers. We used a straightforward hole as an example, but a hole with a narrower fairway or one with penalty areas will change your calculation of how hard to swing.

The takeaway, then, is to use our example and apply it to your own game and golf course. Determine how much farther your all-out swing travels, and how much straighter your fairway-finder swing goes.

As we show, it may not be worth it to give up 30 yards to find the fairway on most holes, but if there are penalty areas and OB in play, you might save strokes by dialing it back.

Verdict

Powell and Weinman’s all-out swings traveled over 30 yards farther than their easy swings, but they produced a dispersion that was twice as wide. When applied to a generic 350-yard hole with 40-yard-wide fairways, however, the stats show that they would both be better off with their 100 percent swing, even if that finds the rough. On narrower holes with penalty areas, OB and bunkers, this calculation might shift and reward a fairway-finder swing.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com