[PHOTO: Oisin Keniry/R&A]

For all his scientific precision and analytical approach to golf, Bryson DeChambeau has encountered one variable that defies his calculations: the wind. It’s a struggle that reached its nadir last year at Royal Troon, where the elements exposed the glaring weakness in an otherwise formidable game.

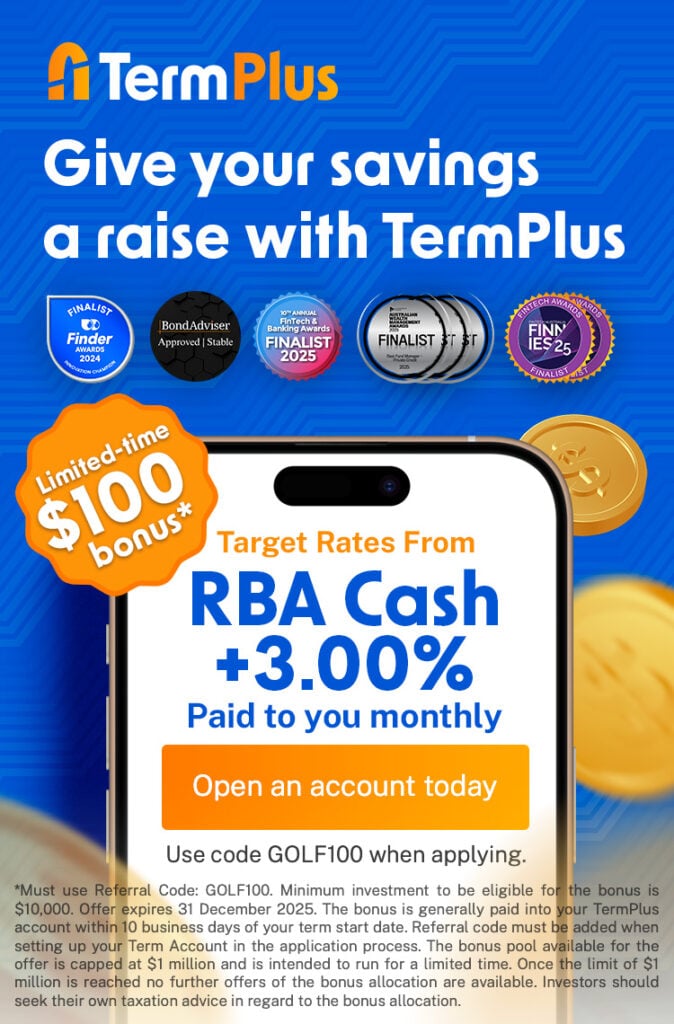

RELATED: Get ‘Bryson Ball Speed’

DeChambeau arrived in Scotland last July as the reigning US Open champion, fresh off a performance that silenced doubters about his staying power. His runner-up finish at the PGA Championship and T-6 at the Masters had sparked conversations about how good the “Mad Scientist” truly was and where his unconventional methods might ultimately take him. Those discussions came to an abrupt halt when the elements of Royal Troon dismantled his game piece by piece. Because, while a single poor showing might be dismissed as an anomaly, DeChambeau’s Open Championship record tells a more troubling story. In seven appearances he has cracked the top 30 just once. The irony is bitter: a two-time US Open winner who can overpower golf’s most physically demanding test, who has contended at back-to-back Masters Tournaments and finished T-4 or better in four of his past five PGAs, becomes a shadow of himself when the claret jug is at stake.

“I finished eighth at St Andrews,” DeChambeau said last year while en route to missing the cut at Royal Troon. “I can do it… when it’s warm and not windy.” The quip drew laughs, but beneath the humour lay a painful truth about his Achilles’ heel.

RELATED: Open Championship 2025 – Ryan Peake receives dream group at Portrush, Aussie tee-times AEST

DeChambeau has attributed some of his Open struggles to equipment and ball speed considerations, yet such consistent underperformance against his increasingly impressive résumé at other majors cannot be so easily explained away. The wind, that most democratic of golf’s challenges, has proven to be his kryptonite.

Speaking to the press overnight (Australian time) at Royal Portrush, DeChambeau acknowledged he’s altering his approach to battling wind this week, benching brute force for precision and patience.

“I think building up hitting it and using the wind, playing into the wind a lot more, not trying to ride the wind is something that’s pretty simple to talk about but sometimes difficult to execute when it’s a unique scenario, depending on where the hazards are and the bunkers are and trying to get a certain shot to a certain place, just being a little more strategic,” DeChambeau said. “That’s what we’re looking at doing this week is just try to be as strategic as possible and put the ball in a place where I can give myself good chances for birdie but also not give myself too many difficult places to play from is the goal.”

The mental gymnastics required to combat wind’s unpredictability have clearly weighed on DeChambeau. Unlike the controlled environment of parkland golf, links golf presents infinite variables that resist his analytical nature.

“You’re feeling the wind, how much it’s coming into you and if it’s off the left or right a lot more than normal,” DeChambeau said. “OK, how do I feel? How do I turn this into the wind? If you’re going to try to ride the wind one time, how do I control and make sure it doesn’t go into a crazy place? Because once the ball goes into that wind, it’s sayonara. That thing can go forever offline.”

RELATED: Xander Schauffele covets his major victories, just don’t ask him where the trophies are

The solution, DeChambeau believes, lies in experience and simplification. He’s spent considerable time in windy conditions, both at Opens and other tournaments, gradually building comfort through repetition rather than theory.

“All I’ve really done is hit more half shots and tried to play into the wind a lot more,” he said. “If it’s a left-to-right wind, I’ll draw it. If it’s a right-to-left wind, I’ll try to cut it more often than not.”

True to form, when asked about unconventional practice methods, DeChambeau’s eyes lit up at the mention of wind-tunnel training. “This is going to be wild, but imagine a scenario where you’ve got a 400-yard tent, and you can just hit any type of shot with any wind with all the fans,” DeChambeau said, his enthusiasm building. “That’s what I imagine, like in a hangar or something like that in a big stadium. Wouldn’t it be cool to test in a massive wind tunnel? Yes, I’d for sure do that. I’d love that.”

For now, DeChambeau carries the weight of expectation and the burden of past misses, as he tries to solve what has vexed him – perhaps with the realisation that some equations cannot be solved, only adapted to.