If you wanted to divide the Ryder Cup into eras, you could come up with four pretty easy distinctions:

- U.S. Dominance, 1927-1981—America goes 20-3-1,

- The Golden Age of Parity, 1983-1999—Team Europe emerges, almost every Cup decided by a point or less

- European Dominance, 2002-2014—They win six of seven, often humiliating the Americans

- The Home Blowout, 2016-Present—five straight Cups won by the home team, closest margin 5 points

It has now been a decade inside our current era, and I’ve come to believe the most important and most interesting job of a Ryder Cup analyst is to try to figure out why the home team keeps dominating. I gave it a shot after the Rome debacle, and came to the conclusion that it had to be the fans—the current culture of loud, drunken and, frankly, mean partisan support has cultivated an intimidating environment for the away team, and unlike a team sport, professional golfers have no chance to get used to it because they only see it once every two years.

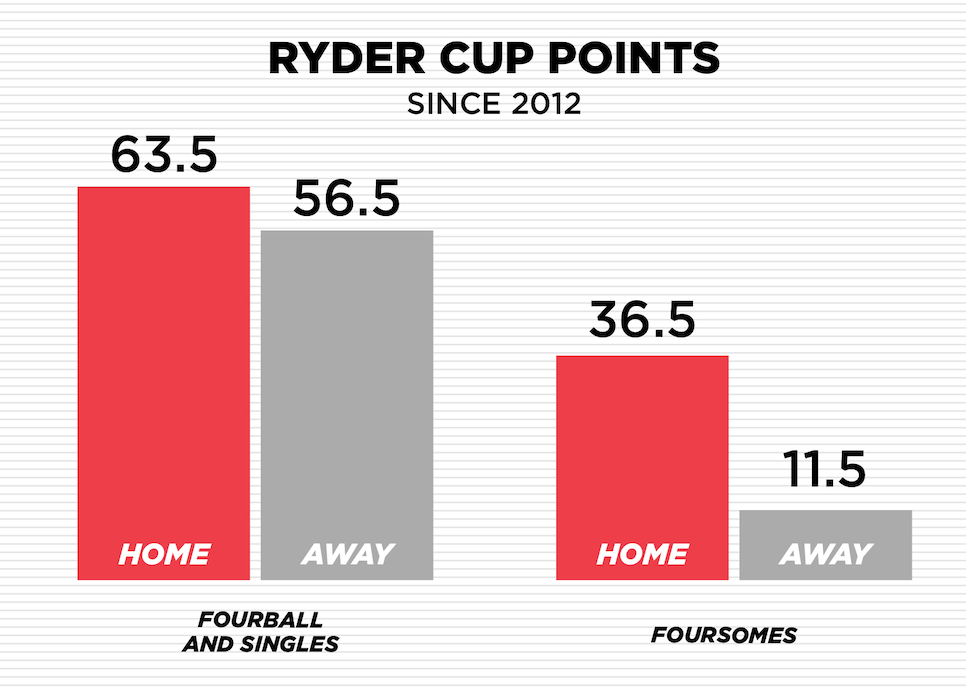

It’s a nice theory—and very much a true theory in the sense that it’s not provable—but there’s one nagging statistic that makes things really complicated. As you likely already know, there are three different match-play formats at the Ryder Cup: singles (12 matches), fourball (8 matches), and foursomes (8 matches). Singles is self-explanatory, fourball is a two-on-two format where each player plays his own ball, and foursomes is what we commonly call alternate shot. First, I want to show you the record of the home team in singles and fourball combined since 2012*:

63½-56½ (52.92 percent)

(*I’m including 2012 since that was the first year when the home team began dominating in pairs sessions*)

That’s not much better than .500, and is pretty much what you’d expect of a “normal” home-course advantage (or even less—NBA home teams, for instance, win around 55-60 percent of their games, while the NFL tends to be around 53 percent).

Now look at the record of the home team in foursomes:

36½-11½ (76.04 percent)

Pretty wild, right? Ryder Cup statistics are always at the mercy of the “small sample size” argument—this thing only happens once every two years—but a data set of almost 50 matches over a decade and change really starts to seem meaningful. It also seems to debunk the fan theory, because if fans were really so impactful, you’d expect them to have the same impact on all formats, not just one.

So, how do we explain this?

The first thing we have to look at is what makes foursomes unique, and of course that comes down to the intricacies of the alternate-shot format. With different players teeing off on every hole, playing one ball per team, the ability to manipulate lineups to your advantage is huge. Here’s how Justin Ray, who has worked with the U.S. team at the last two Solheim Cups for the 21st Group and doubles as the unofficial czar of Twitter golf stats, put it:

“Alternate shot is the format where the numbers and the sequencing of players has the biggest impact … this is the format where it’s most impactful.”

The elements that go into this are manifold. On the surface, you have important considerations that range from player chemistry to ball compatibility (something Padraig Harrington famously neglected until the last moment at Whistling Straits), but when you get granular, you start looking at things like who will be teeing off on the most par 3s, who’s hitting the most drivers, who hits the most lag putts versus short putts, right down to who excels at the expected approach distances. Those factors are considered for each match, and then have to be plugged into a best-fit puzzle for all four matches across the session. You can see how it would get very complicated, very quickly.

Jason Aquino is the head of Scouts Consulting, which has been working with the U.S. Ryder Cup team since Hazeltine National in 2016 as its research arm, and he’s had a front-row seat to the home blowouts of the past 10 years. He called the process “idiosyncratic,” but also pointed to examples like last year at the Presidents Cup in Montreal, when the majority of the par 3s were on odd holes, and the player teeing off on those holes barely hit driver all day.

“If you think about it,” he said, “the guy teeing off on the even holes is playing a very different golf course from the guy teeing off on the odd holes.”

Aquino also gave me an interesting stat—since 2012, the average score of a player at the end of a Ryder Cup singles match was 2.7 strokes under par. For foursomes, that average score was just 1.2 strokes under par. In both formats, one ball is being played, but having teammates combine in the alternate-shot format makes things a shot and a half harder, on average.

That all feeds into a point both Aquino and Ray emphasized: Foursomes is volatile.

We’ve seen that volatility play out time and time again. At 2016 in Hazeltine, the Americans won the morning foursomes session on Friday 4-0, and never looked back on the way to a rout. Two years later, in Paris, Europe played fourball first and trailed 3-1. Thomas Bjorn, near panic, thought about changing his alternate-shot teams, but his stats team convinced him to hold firm, and in the afternoon, the Europeans won the foursomes session 4-0. At Whistling Straits, three years later, the Americans started with foursomes, dominated 3-1 both Friday and Saturday, and by Sunday the Europeans had no chance in singles. And then in Rome, 2023, Luke Donald decided that because Europe had been so good at home in foursomes, he should do it first instead of second. It was a good choice—Europe won 4-0, and the Cup was essentially over before the American fans back home had even woken up.

However, volatile as the format has been, you’ll notice that since 2012 it has been volatile in favor of the home team. Which leads us to our next question: We know foursomes can be influenced by statistical tactics, but why does that only seem to apply to the home team?

RELATED: How the U.S. could avoid the same mistakes made two years earlier

This question is much harder. I thought it might have to do with course setup, as in, maybe the home team can doctor the tee and pin locations to custom fit their players to hit the perfect shots at the perfect time. In fact, though, both pins and tees are set by a neutral committee, and teams are only told of the locations early in Ryder Cup week (and in fact, they aren’t even told which of the locations they receive will be used for which session). In other words, in terms of course setup, there shouldn’t be a huge advantage to the home team.

1 / 10

Dom Furore

2 / 10

The menacing surrounds at Bethpage Black’s sixth green.

Dom Furore

3 / 10

Stephen Szurlej

4 / 10

The view behind the sixth green from 7 tee.

Stephen Szurlej

5 / 10

The ultra-difficult stretch of Bethpage Black’s par-4 10th (right), requiring extreme precision off the tee, with the 11th hole—a Pine Valley-like par 4 that also requires a ball stay out of the extended bunker lobes.

Stephen Szurlej

6 / 10

The 517-yard, par-5 fourth hole is guarded by a classic cross bunker.

Stephen Szurlej

7 / 10

Stephen Szurlej

8 / 10

The par-4 12th’s widened fairway gives golfers a bailout option.

Stephen Szurlej

9 / 10

Behind the 16th green.

Stephen Szurlej

10 / 10

Bethpage Black’s home hole.

Photo by Stephen Szurlej

Previous Next Pause Play Save for later Public Bethpage State Park: Black Farmingdale, NY 4.6 41 Panelists

- 100 Greatest

- 100 Greatest Public

- Best In State

Sprawling Bethpage Black, designed in the mid-1930s to be “the public Pine Valley,” became the darling of the USGA in the early 2000s, when it brought the 2002 and 2009 U.S. Opens here. Then it became a darling of the PGA Tour as host of the 2011 and 2016 Barclays. Now, the PGA of America has embraced The Black, which hosted the 2019 PGA Championship (winner: Brooks Koepka) and the upcoming 2025 Ryder Cup. Heady stuff for a layout that was once a scruffy state-park haunt where one needed to sleep in the parking lot in order to get a tee time. Now, you need fast fingers on the state park’s website once tee times are available—as prime reservations at The Black are known for going in seconds. View Course

I turned back to the experts for their opinion, but the problem with Justin Ray is that the only time he’s advised the American team in an away Solheim Cup (Spain, 2023), they dominated the foursomes session, winning 4-0 on Friday.

“I’ve worked for a road and home team event,” he said, “and found it to be pretty much identical in terms of the prep we did. From my experience, I don’t think there’s an overwhelming difference.”

And as far as the Ryder Cup foursomes disparity, he could only say, “it’s difficult to find a real great mathematical reason why it’s been so overwhelming.”

I thought I’d do better with Aquino, who has been on the front lines for the home massacres, both good and bad. In fact, though, he was just as stumped as Ray.

“I wish I could pinpoint a particular reason for you,” he said. “It’s so disappointing for me to not be able to give you a good reason.”

Later, he cautioned me against drawing any major conclusions, even from a decade’s worth of data.

“You’re entangling this phenomenon [of volatility] with the home team, and I’m saying, I disentangle that,” he said. “I think it’s entirely idiosyncratic to the nature of foursomes.”

When I put him on the spot, he said that he wouldn’t be surprised if the next five Ryder Cups return a completely different set of results in foursomes. And the impression I took away from both him and Ray is that they more or less considered the gaudy home foursomes number statistical noise.

So where does that leave us? Well, pretty much with a great big question mark. On paper, we have a very blatant, very lopsided disparity in one format that has persisted across 50 matches and 13 years, and seems to explain the era of the home blowout. But even the literal smartest guys in the field aren’t quite sure what’s going on, or whether it will continue. We’re left, then, with an enduring mystery that might never be solved: We know how the home team is winning the Ryder Cup, but we don’t seem to know why.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com