A timely intervention from Peter Thomson had a powerful influence on Ian Baker-Finch’s nascent career.

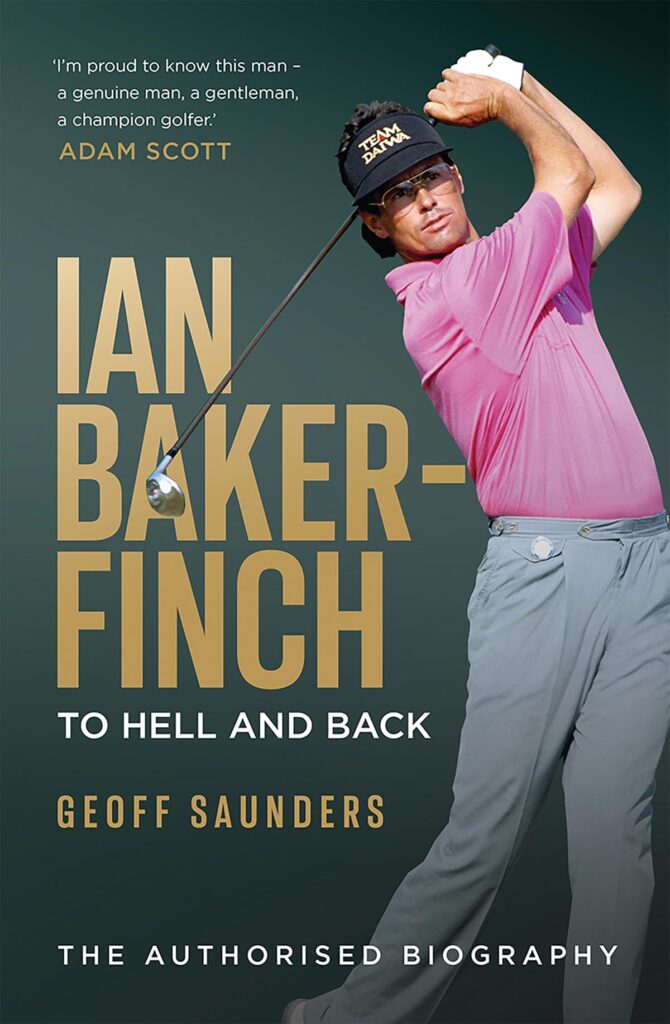

This is an edited extract from Ian Baker-Finch: To Hell And Back by Geoff Saunders, published by Hardie Grant Books. Available in bookstores nationally and online. RRP $49.99, $NZ54.99.

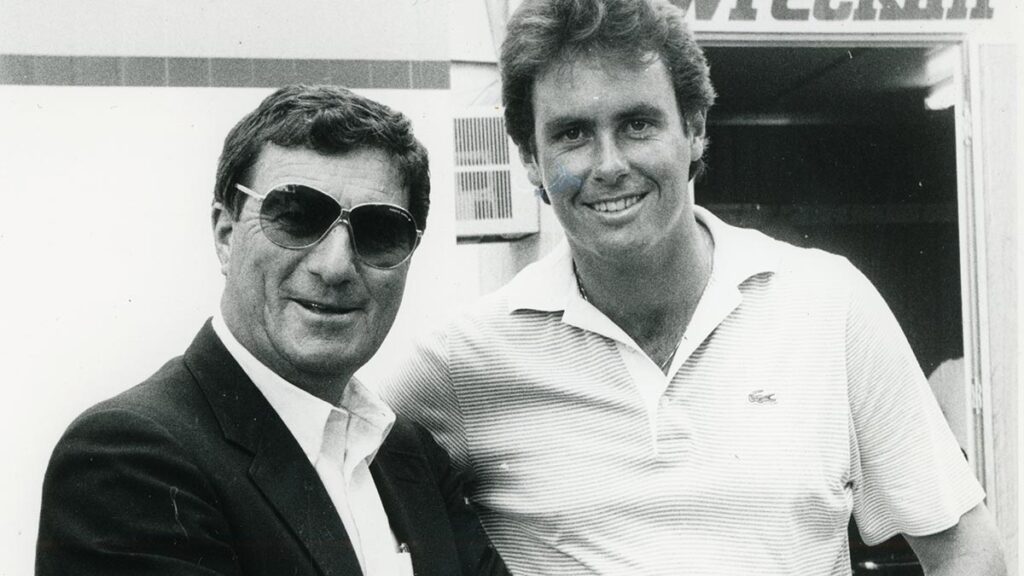

The beginning of Ian Baker-Finch’s long-term friendship with fellow Australian and five-time Open Champion Peter Thomson was a milestone in his career. Thomson’s interest in the young Queenslander was sparked by Ian’s ability to run hot in streaks, and the all-time great’s suggestion that Ian should go to New Zealand at the end of the 1981 season was perfectly timed. Over the next three or four years, a series of low-key interventions from Thomson were important factors in the development of Ian’s career.

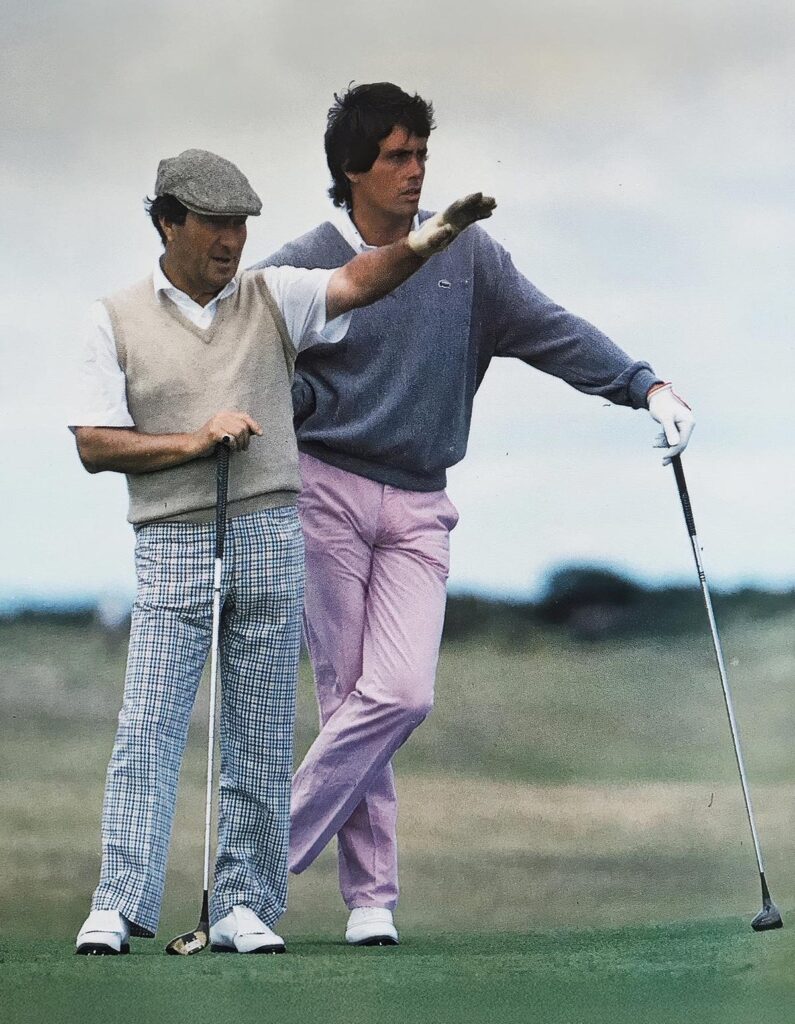

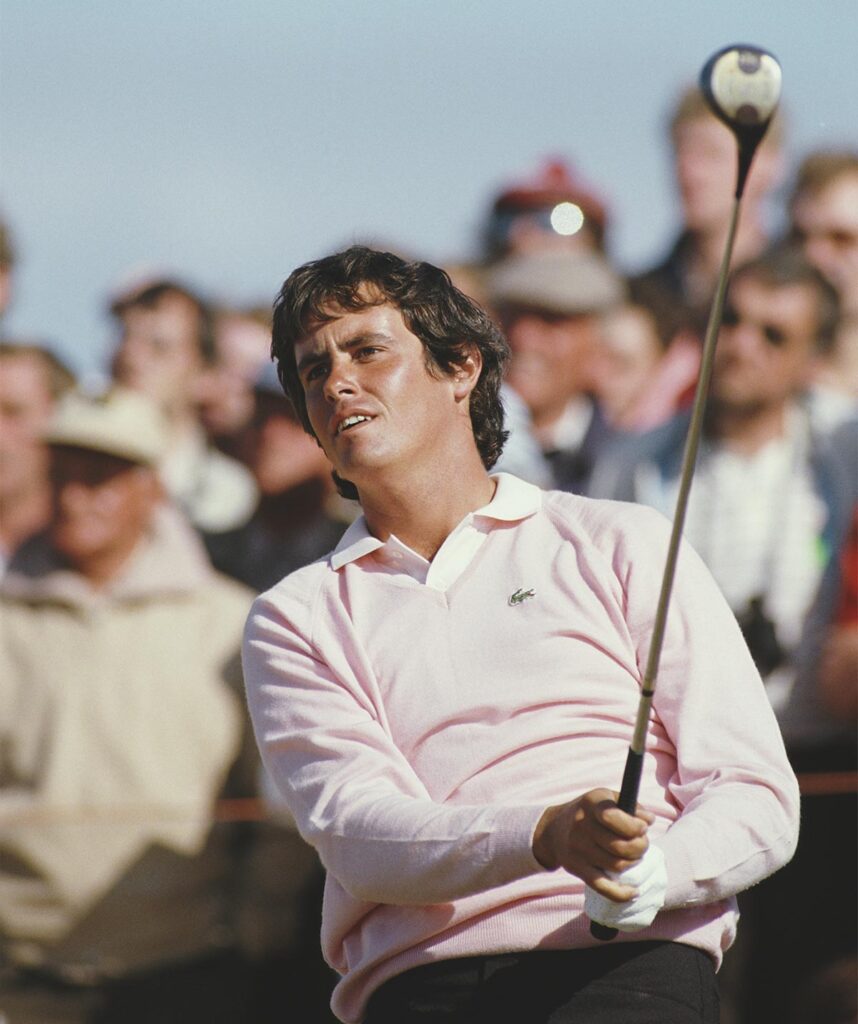

It was an unlikely friendship in many ways. There was a 31-year difference in age between the two men, and in 1981 they were at quite different stages of their careers. Peter Thomson was 52, with five Open Championships to his name, secure in his position as Australia’s greatest golfer. Ian was a 21-year-old tyro, showing the odd fleeting sign of promise. Their clothing tastes were very different, but each had a distinctive style. Thomson dressed in muted greys and whites, favouring the button-up cardigan, paired with his preferred plain-white Dunlop shoes. It was his own look, not unlike his idol Hogan’s – understated and classy. The young Baker-Finch’s preference was for bright colours, often pink, and chequered, flared trousers. New Zealand Sunday Times writer Peter Williams described Ian as follows: “Tall, suntanned, with dark hair flowing to shoulder length, Baker-Finch has all the physical attributes needed to become a sporting pop star.”

There was little or nothing of the pop star in Thomson. The two men may have been from different sartorial planets, but this presented no barrier to the bond developing between them from 1981 – they had become master and pupil.

Thomson was a remarkable man and there was far more to him than his unquestioned ability as a player. The veteran champion had reached an interesting stage in his own golf career. For decades he had pursued his many and varied interests outside tournament golf. He had been a long-time columnist for The Age newspaper in his hometown Melbourne, a television commentator and president of the Australian PGA from 1962 to 1994.

In early 1982, Thomson even became embroiled in the rough and tumble of politics. However, he was badly mauled in his first and only attempt to enter the political arena. A dramatic swing against the Liberal Party on polling day thwarted his bid for a seat in parliament.

The end of Thomson’s political aspirations presented him with the opportunity to pursue a short but extraordinarily successful senior golf career in America from 1984, on what is now the PGA Tour Champions.

At the time of meeting Ian, the multi-talented Thomson was also involved in his thriving golf course design practice with friend and partner Michael Wolveridge. The business started in 1965 in conjunction with Commander John Harris, a prolific English architect who had designed 250 courses, mainly outside the UK. South Pacific Golf Pty Ltd had developed from there into the international practice of Thomson Wolveridge & Associates. Thomson did not retire until the age of 86, after 50 years in the golf course design business.

Despite his other interests, Thomson still found time to mentor a few young golfers who were making their way through the ranks. His advice to the young hopefuls was frequently delivered in his typically dry style. One young pro sought Thomson’s counsel, expecting detailed advice from the great man. Thomson cryptically advised the crestfallen young player his way forward was to “shoot lower scores”.

The senior pro observed 21-year-old Ian had talent coupled with a good work ethic but required some guidance with his swing. However, Thomson never assumed the role of a full-time coach with his interest being mainly paternal. Ian described Thomson’s role as being like a father figure, noting, ‘Peter was always there when I needed him.’

Thomson’s method and approach to the game was quite different from Ian’s and that of Ian’s boyhood idol, Jack Nicklaus. Thomson played golf in America at an early stage of his career – and did not enjoy it. The courses he encountered in the States were, in the main, heavily watered and in poor condition. Golf in America was also played mainly in the air.

Thomson preferred the fine turf and classic courses of Britain – bouncy, firm, with the wind adding another dimension. Most of the famous Open venues were seaside or ‘links’ courses. His game suited such conditions as he quickly developed into the finest links player in the world. Strategising his way around the course, Thomson focused on where the ball should land and, equally importantly, where it would roll upon landing.

He made the United Kingdom his domain for 22 years from 1951 to 1973, during which time he never missed a cut in an Open. He won the claret jug three times in a row from 1954 to 1956, again in 1958, and then a fifth and final time in 1965, silencing the critics who had suggested his first four Open wins had been played against less than world-class opposition. In his 1965 Open win at Royal Birkdale, he overcame a new generation of players – including Nicklaus and the two other members of the ‘big three’, Palmer and Player.

The Melburnian’s overall record in The Open is barely believable: five wins – bettered only by Harry Vardon’s six and equalled by three others, James Braid, J.H. Taylor and Tom Watson – three times a runner-up and 18 times in the top 10 in his 30 appearances.

Thomson’s swing was characterised by its simplicity and effectiveness. He learned the game in Melbourne playing on quick greens and fast courses with their abundance of run, especially in summer. He set himself up beautifully to the ball, an area in which he exercised particular care. No excess movement was evident in his method, and seemingly little effort expended in his delivery of a flat swing appearing to be remarkably similar to his idol Ben Hogan’s. While Hogan may have been an enigma to many of his fellow golfers on tour, Thomson became close to him in the 1950s, discovering they shared a similar dry sense of humour. He believed the dour little champion from Texas was the finest golfer he had seen and ranked Sam Snead not too far behind Hogan.

But by 1982, Ian’s early devotion to the Jack Nicklaus method was causing problems for him, resulting in a high, weak fade off the tee and a lack of length. The 53-year-old Thomson was there and ready to help, quietly and understatedly stepping in to help the struggling young pro. In 1991, Ian looked back on his problems of the time, telling Peter Mitchell, author of The Complete Golfer, “At the end of 1982, I was having a lot of trouble because I’d always tried to play like Nicklaus by hitting the ball high with fade, but I was never powerful enough.”

Ian reflects on his problems with his ball-striking during this period. “I was in New Zealand for the airline’s tournament (the Air New Zealand–Shell Open), and we had to practise down at a narrow park not far from Titirangi Golf Club. I was over to one side, hitting these pathetic, weak fades. Peter just happened to be walking past and watched me hit some dreadful shots to the right and on to the road. He stepped forward and said, ‘OK, now is the time. I think you should do this.’ It was the first time he changed my swing around.”

The cure was to turn further and swing flatter. The impromptu lesson took place at Shadbolt Park, home of local rugby club Bay Lynn and walking distance from Titirangi’s 16th and 17th holes. Peter Headland was an Australian touring pro at the time and happened to walk down to the practice fairway, observing the lesson in progress with interest. “Ian was a lovely guy then but was certainly no world-beater. He stood open at address and had a big lateral movement off the ball with his arms and the club very high at the top of his backswing. I was quite taken aback to see Peter patiently teaching Ian to stand squarer, even slightly closed. The next step involved Peter telling Ian to swing around himself more and to lower his arms and the club. He was being taught a method exactly the opposite of his existing way of swinging. Right from that moment he started to play well, and his high weak cut disappeared.”

Ian’s feet had been repositioned, and he immediately started hitting lower draws down the middle of the makeshift practice area. The lesson from Thomson was timely and effective, the tuition at the unlikely venue bringing Ian’s 1982 season to a close.

Decades later, Ian still recalls Thomson’s intervention. “The lesson from Peter in New Zealand was the start of it for me. I can still visualise everything he did for me at the time.”

Mike Clayton also remembers Thomson’s advice to Ian. “Peter was not a teacher at all, but he had a technically great swing. He knew the opposite of a high cut was a low draw and Ian told me Peter told him to ‘put the ball back in my stance and swing around my arse’. It made perfect sense. It completely changed Ian’s swing and it was so

much better.”

Early in his career, Thomson had himself benefited from mentoring by the trailblazing Norman Von Nida, one of Australia’s greatest players, and one of the first to travel abroad to earn his living as far back as the late 1940s. The mentorship went to the extent of the pair agreeing to pool their prizemoney and share expenses during Thomson’s first visit to the UK in 1951.

When Ian travelled to Melbourne for tournaments he would often stay with Peter and Mary Thomson, but with the end of the 1982 season came the unexpected invitation for him to spend a few weeks with the Thomson family at their holiday home in Sorrento on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, an hour or so south of Melbourne. Ian accepted with delight and spent a relaxed four weeks with the family over the Christmas holidays, playing golf each day with Thomson on the courses nearby.

He recalls, “Peter and I would walk out the back of the Thomson holiday house, cross the road, jump on to the Portsea course and play together. We would also play at Sorrento – I cannot recall how many rounds we played together in the area, but it was a lot of golf.”

Ian reflects on why Thomson took so much interest in him. “I think he could see how much I wanted to succeed at golf. We played a lot of golf and spent a great deal of time together.”

Ian recalls some advice delivered to him in Thomson’s dry style. “I asked Peter what he did to exercise for golf, and he said, ‘I walk – what else would I do?’ So, we would walk the beach together. After playing golf with him I would want to go and hit balls, but he would say, ‘Take four balls and go and play 17 and 18 – practise making two 4s to win.’ He would tell me to think more deeply about what I was doing. He was not a big beater of practice balls.”

Thomson had a long association with Portsea Golf Club, and Sorrento Golf Club was nearby, as was Flinders Golf Club, on the eastern seaward side of the peninsula. Thomson enjoyed the cluster of courses around his holiday home and once labelled Flinders “a distant cousin to Pebble Beach and a relative of Muirfield”.

Ian felt understandably honoured by the invitation and the intensive coaching he received from Australia’s most famous golfer. The new concept of rotating his shoulders further was working for him, and the swaying and tilting in his swing gradually disappeared. He had previously formed a friendship with Peter and Mary Thomson’s daughter Peta-Ann, known as Pan. Several of Ian’s contemporaries were convinced, wrongly as it turned out, the main motivation for Thomson’s interest in coaching the young Queenslander came from the existence of the friendship between Ian and Pan, and they gave Ian a tough time as a result.

Ian took maximum benefit from the time spent with Thomson at the end of 1982 and beginning of 1983. He says, “I could fill a whole chapter with what Peter taught me. He passed on to me these pearls of wisdom about scoring and winning – quite simple things I still remember today. It was just what I needed at this stage of my career. I needed to get away from the circuit for a time and look at how I played golf. It was not as though I was getting lessons from Peter for hours. It was a far more subtle kind of support. He would say to me, ‘You can’t play in the wind like that, my boy. You don’t want to hit a high fade; you need to learn to hit a low draw.’ Another example is how he taught me to flight the ball better. Instead of trying to hit a hard wedge, he taught me to put the ball back in my stance and play an easy 9-iron. I became very good at the half shot with a hold-off finish. I used that technique a lot, as Thommo taught me.”

Then there was the wisdom of Thomson’s bank of course-management knowledge. He told Ian, “Look carefully at the pin position and find the best place to land, but also bear in mind you are rarely in a bad position in the middle of a green, and on windy days always play to the middle of the green.”

Ian’s technique was improving but he was also assimilating skills from Thomson on learning how to score, how to think his way around the golf course and, most importantly, how to win. It was the Peter Thomson way.

In 2023, Mary Thomson, having just celebrated her 90th birthday, recalled the unique relationship between her late husband and Ian. “Ian stayed with us regularly in Melbourne in his early days as a touring professional. I know Peter was very fond of him and saw great potential in him. He saw Ian as a future champion.”