With the US Open at Los Angeles Country Club’s North course this week, it will mark the sixth time since 1999 the championship has been played on a course that’s never previously hosted a US Open, joining Pinehurst No.2 (1999), Bethpage’s Black Course (2002), Torrey Pines’ South Course (2008), Chambers Bay (2015) and Erin Hills (2017).

It will be the last time the US Open visits a new site until at least 2031, the next vacant date on the USGA calendar. All other sites until then have previously hosted the event.

Any first-time US Open venue arouses a level of interest and curiosity beyond what accompanies a return to a Winged Foot or a Pebble Beach, but there’s a particular intrigue surrounding Los Angeles Country Club’s North course, a historically inward-looking club that only recently has pulled the curtain back on its highly regarded North course. A rugged piece of nature surrounded by the glitz and modernity of Los Angeles, it’s a broad, flexible course with a unique topography, a diversion from a traditional US Open design.

Being new to the major championship rotation (it will host again in 2039), there’s much to learn about its history and character – and why course enthusiasts are so excited for the 2023 US Open. Here are some of the fundamentals you’ll need to know in preparation for LACC.

THE USE OF BARRANCAS

When golf sites were more agrarian during the golf boom of the 1920s, architects in Los Angeles used the naturally occurring barrancas creatively as hazards, and most of the courses of the era still feature barrancas as significant playing obstacles. At Los Angeles Country Club’s North course, the barrancas feature prominently on the first nine, factoring into the design of seven holes.

THE “COURSE WITHIN A COURSE” CONCEPT

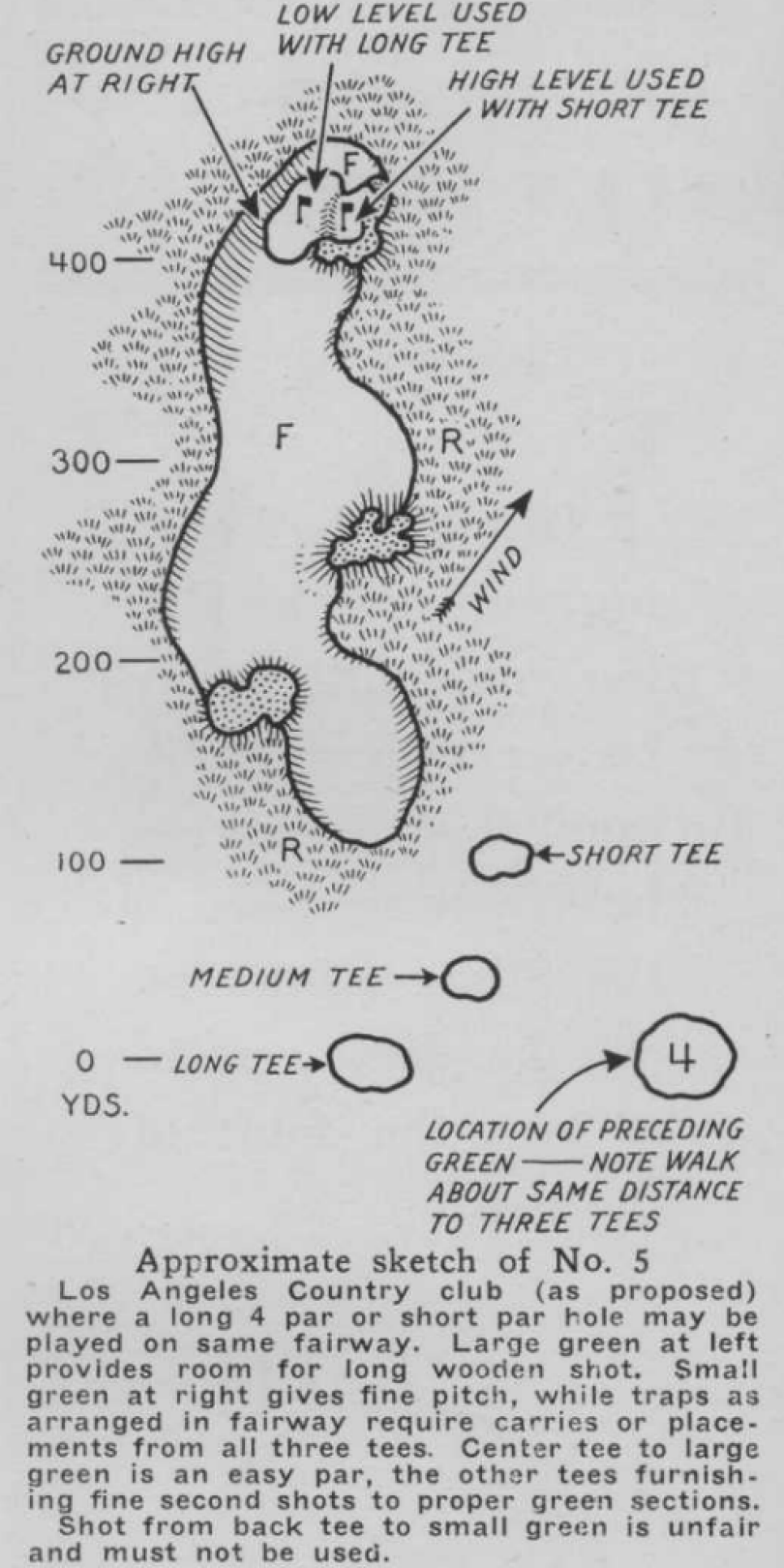

One of the groundbreaking components of Thomas’ 1926 remodel of the North course was his concept of a “course within a course”, or what he labeled as the design’s “diversity”. At many holes he constructed tees at various intervals and orientation to the fairways so that they could be set up differently whenever desired, maximising the course’s day-to-day appeal. One day the ideal shot shape on a par 4 might be left-to-right from a particular forward set of tees, and the next right-to-left from longer tees oriented at an opposite angle. The course could be played from all short tees in one instance, then converted to a championship setup in another.

While holes with multiple tees are common today, this was a fresh idea in the mid-1920s. The North course retains that diversity with par 3 holes like the seventh and 11th that can range from shorter than 200 yards to nearly 300 yards with different pathways into the greens. In fact, the seventh can be stretched into 320-yard par 4, and even as a 290-yard par 3 it might play longer in some setups than the previous sixth, a downhill driveable par 4. The USGA will have all these options at their disposal during the US Open.

A RARE GLIMPSE INTO GEORGE THOMAS’ WORK

Originally from Philadelphia, Thomas was a man of diverse interests and talents. He was an author, a breeder of dogs and noted horticulturist with a specialty in cultivating roses. He’s best known as a golf course designer for his work creating some of southern California’s – and America’s – most enduring pieces of architecture.

He moved to Los Angeles about 1920 and joined Los Angeles Country Club. He devoted himself to the pursuit of golf design, and over the ensuing years became one of the profession’s most creative thinkers, building a number of courses (many with the assistant of William P. “Billy” Bell) and developing advanced theories on strategy and versatility as expressed in his seminal book, Golf Course Architecture in America. Though his overall portfolio was small compared to his peers (perhaps just 20 courses), his work was profoundly influential, particularly his three Los Angeles masterpieces: Los Angeles Country Club’s North course (ranked 16th on Golf Digest’s America’s 100 Greatest Courses); Riviera (18th); and Bel-Air (135th). He died in 1932.

A HAT TIP FOR WILLIAM P. “BILLY” BELL

Billy Bell was a construction specialist in the 1920s who worked closely with Thomas on many of the architect’s California designs. Bell’s work shaping bunkers, giving them elaborate curtain-fold shapes and thick eyebrow grass edges complimented the strategies and visual compositions of Thomas’ holes. His rough-hewn bunkers have morphed into clean, sweeping shapes at Riviera, but have been restored at Los Angeles Country Club’s North course by Gil Hanse and Jim Wagner, and at Bel-Air by Tom Doak.

Bell worked with Thomas until the early 1930s, then joined with his son, William F. Bell, known as Billy Bell Jnr, who became one of the west coast’s most prolific architects after World War II.

THE NORTH COURSE GETS THE SPOTLIGHT

Established in the late 1800s and operated at two different sites before finding its permanent home in 1911 in the current location, the club’s first courses at this site were laid out over the mostly treeless farmland of the agricultural plain extending towards the Santa Monica Mountains, but today the club is bordered by some of the most expensive real estate in the US, with Beverly Hills to the east, Century City to the south-east, Westwood to the west and Bel-Air and Beverly Crest to the north.

The base routing for the North course was laid out in the early 1920s by British architect Herbert Fowler. George Thomas, a newly joined member of the club who had designed several courses around his native Philadelphia, carried out the construction work for Fowler. During the next five years, Thomas’ impressions of proper golf course design evolved and the club asked him to redesign the North course in 1926.

Thomas kept several of Fowler’s holes and green sites, but the design was otherwise entirely re-engineered. He created broad holes that allowed members to choose different lines of attack into the greens depending on ability, and deep, severe bunkers that forced a critical assessment of one’s skills. Most importantly, he utilised the property’s tilted, broken topography in strategic ways that rewarded players who took on the greatest risk but didn’t overly penalise lesser capabilities, giving them routes to bounce balls onto greens if the slopes were utilised intelligently.

The North course underwent a number of renovations through the years, including one by John Harbottle in the 1990s. During a sympathetic restoration in 2009 and 2010, architects Gil Hanse and Jim Wagner returned many of the original features that had been dulled or modified over the decades. The course that participants will play in the 2023 US Open is a faithful expression of Thomas’ original vision, though much longer at more than 7,500 yards (6,850 metres).

BUT THE SOUTH COURSE IS STILL ONE OF CALIFORNIA’S BEST

Thomas also remodelled the club’s South course in 1926, implementing many of the same strategies and expressive bunkering. The South, renovated by Hanse and Wagner in 2016, has always been a strong, engaging design on its own. If it existed elsewhere else in Los Angeles it would likely be more highly regarded than it already is, but the course is perpetually overshadowed by the North. It will prove vital for overflow, spectator areas and tournament staging during this US Open.

ANOTHER CHANCE TO ENJOY THE WORK OF GIL HANSE AND JIM WAGNER

Based in Philadelphia, Hanse and Wagner are the most sought-after architects in the business for their renovation and remodel work at historic clubs like Merion, Winged Foot West (and East), The Country Club, Southern Hills, and current work at Oakmont and Olympic Club. Original designs at Ohoopee Match Club in Georgia, Boston Golf Club, Streamsong Black in Florida and Pinehurst No.4 are all ranked among America’s 100 Greatest or Second 100 Greatest Courses, and new designs at Fields Ranch East at PGA National in Frisco, Texas, Ladera in California’s Coachella Valley, and Apogee Club in Florida have also generated excitement.

Hanse and Wagner began restoring the size and shaping of the North Courses’ Thomas/Bell bunkering in 2009 and 2010. The recapture of the distinctive look encouraged the club to further return the design as close as possible to Thomas’ 1926 program. This included the rebuilding of all putting surfaces and the expansion of the edges out to their intended perimeters; the restoration of greens at the second, sixth and eighth in their original locations; adding tees to enhance the “course with a course” flexibility; removing trees and broadening fairways to recapture the spaciousness of the property; and the remediation of the site’s barrancas to their native, naturalistic look.

The North course has climbed continuously in the America’s 100 Greatest ranking each cycle after the Hanse and Wagner renovation.

A CHANCE TO SEE A CLASSICAL ERA COURSE PLAY FIRM AND FAST

Firm and fast fairways are the key to making the architecture at the North course work. Unlike when US Opens are played at tighter courses like Merion, Oakmont or Torrey Pines where heavy rough enforces straight driving, the Tifway II Bermuda fairways at Los Angeles Country Club are broad and comparatively undefended. Given its width – fairways will range from 35 to 60 paces across – the defence of the course has to be firm, dry surfaces that play like a British links and cause balls to roll and drift into bunkers, awkward stances or moderate rough (also Tifway II and Bandera Bermuda) that will impact distance control into the firm, bentgrass greens (they are Pure Distinction bent).

USGA chief championships officer John Bodenhamer understands that George Thomas’ architectural setup combined with bouncy fairways and firm greens will mean that only players in total command of their driving and approach play will be able to score. He and the maintenance staff will have the playing surfaces as racy as possible, as long as the weather co-operates, not a given considering the weather this year in LA. If the fairways and greens aren’t crisp and dry, players will feast on the course.

THE INGENUITY OF “MOLAR” GREENS

THE USE OF SYCAMORES AS OBSTACLES

Some of the most aesthetically attractive trees on the North course are the twisted white-trunked California sycamores that often grow near the banks of the barrancas. These can be playing obstacles as well, especially on the second shot at the double-dogleg, par-5 eighth and the long, par-4 17th. The North course also features stately eucalyptus trees, while tall pines, planted in the course’s early years, feature prominently on the fifth and 12th holes.

HOW TOPOGRAPHY DICTATES STRATEGY

The canted terrain increases the importance of shaping shots. Drives can be played into the side-slopes of fairways to help control and minimise unwanted rollout, or be carved off the orientation of the hillsides to pick up distance or access garden spots, such as at the par-4 second, par-5 eighth or long par-4 16th. The ground can even be used to reach greens with running shots by using side and foreground embankments. This will be especially helpful in propelling balls on the putting surfaces at the seventh and 11th holes, two par 3s that can each be set up to play longer than 280 yards.

• • •