To explain the importance of Alastair Cochran to the present-day understanding of the science of golf—ball, club, swing, statistics, strategy and all things in between—would be like trying to adequately encapsulate the impact Alfred Hitchcock played on film, or Alan Turing on computer science, or Johan Cruyff on modern soccer. Everything that matters that we now know began with him.

Cochran, the former lead consultant to the R&A’s Implements and Ball committee but more famously the co-author of the most widely referenced golf science research book in the history of the game, Search for the Perfect Swing, died March 10. He was 94.

It was Cochran’s infectious inquisitiveness that put him at the forefront of modern scientific research about golf from the 1950s into the 2020s. While his Ph.D was in nuclear physics, the former scratch player saw science as vital to improvement for all golfers. He wrote in the preface to the 40th anniversary edition of Search, “It would be an overstatement to say that this book’s publication stimulated manufacturers to apply science and technology to the creation of golf equipment, but I do believe it was one of the triggers. At the very least, the book and the study on which it was based were symptomatic of a growing realization in the early ’60s that science had something to contribute to equipment design, which hitherto had evolved mainly through trial and error.” He went on to write, “I often think that the extremely powerful swings of players like Tiger Woods demonstrate the principles laid out in Search for the Perfect Swing even better than the ’60s golfers used as illustrations.”

Search was the result of an extensive and collaborative research project commissioned by the Golf Society of Great Britain in the early 1960s and first published in 1968. Cochran and John Stobbs, golf correspondent for The Observer, were co-authors, although Cochran coordinated and conducted much of the research behind it. The book’s 35 chapters covered a biomechanical model of the swing (the first so-called “double pendulum” model), the physics of both well-struck shots and the worst mis-hits, lift and drag aerodynamics of the golf ball in flight, the way shafts bent backwards and forwards during the swing and what could be learned from analyzing pro tournaments from statistical and strategic analytics. Its researchers’ early use of computers to understand and predict golf shot trajectories pre-dated launch monitors by four decades, and its theories on the swing’s various components would be verified many years later through high-tech, motion-capture analytics. Cochran himself had conducted wind-tunnel testing for golf research in the early 1960s.

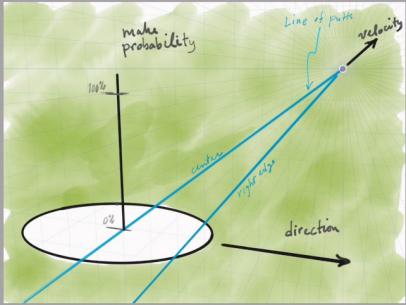

More From Golf Digest  Equipment The science behind why the flagstick should be pulled 99.9 percent of the time

Equipment The science behind why the flagstick should be pulled 99.9 percent of the time  Hot List 2024 Hot List: Our complete review of the best new golf clubs and equipment

Hot List 2024 Hot List: Our complete review of the best new golf clubs and equipment  Hot List 10 myths about golf clubs you should forget right now

Hot List 10 myths about golf clubs you should forget right now

Talking to those who knew him and his work, it is generally acknowledged that Search became “The Bible” of golf science.

“I was lucky enough to know Alastair Cochran for over 25 years and to find myself standing on the shoulders of a giant within the sphere of the science of golf,” said Prof. Steve Otto, Ph.D. and the R&A’s Chief Technology Officer. “The topics within the text range from the origins of strokes gained through to data on putting performance in the 1960s and the ideal weight of a driver—all of which are still relevant today.”

The book was remarkable for not only its thoroughness but its prescience, said Sasho Mackenzie, Ph.D, a professor in the department of human kinetics at St. Francis Xavier University and golf’s leading research expert in the science of the swing and the game.

“I don’t think there has been an equivalent project that comes close to Search for the Perfect Swing in any other sport,” he said. “It may even be unique to any field of study. I’ve accumulated a few hundred papers, presentations, podcasts, etc., related to golf. In every one of them, I could have made a legitimate reference to Search for the Perfect Swing.”

Cochran was the primary figure at the R&A when it came to equipment study and regulation from 1979 to 1997. In 1990, he co-founded with Martin Farrally the World Scientific Congress of Golf, a biennial meeting of golf scientists of every stripe that produced dozens of research papers that ranged from spring-like effect to biomechanics to the yips and sports psychology. Paul Wood, Ph.D, and the vice president of engineering at Ping, now is one of the lead organizers for the WSCG, projecting that same kind of sense of inquiry that Cochran inspired.

“In my opinion Alastair was the most influential golf scientist of our time,” Wood wrote in an email to Golf Digest. “His book still serves as a relevant reference on many aspects of our scientific understanding of the golf swing now. When I started at Ping in 2005 as a complete newcomer to golf, it was the most useful book I read, and I read just about everything published.

“At the R&A, he was an instrumental figure in the transition of the stewardship of the game into an era of measurable and defined rules and regulations.”

That stewardship included the fractious times of the square-grooves controversy in the 1980s and the very beginnings of the debate over how to regulate driver faces that flexed at impact in the late 1990s. In each case, Cochran had researched and understood the possibilities decades before they reached the point of controversy. That tension put Cochran and Frank Thomas, his counterpart at the USGA, square in the middle of understanding complex and previously unexplored scientific concepts in golf and at the same time trying to control their future impacts. Cochran provided an academic’s measured discipline and inquisitiveness with a light touch, once joking privately that the $100 million square-grooves lawsuit that specifically named him didn’t cause much consternation, “I wasn’t too worried—I didn’t have $100 million.”

“For better or worse, he was the yang to Thomas’s yin,” said Jerry Tarde, chairman and editor-in-chief of Golf Digest, who often hosted memorable dinners at the PGA Merchandise Show just to see how the two might jovially spar over this equipment technology topic or that. “He provided a leavening sense of humor, scholarship and stability to all equipment decision-making on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Cochran also worked for a time as a consultant with Callaway, where he interacted with Alan Hocknell, Ph.D., starting in the early 2000s. Hocknell, who’s spent a quarter century at the forefront of golf equipment innovation, became Callaway’s senior vice president for research and development and is now the vice president of advanced research and innovation at Titleist. Hocknell remembers his experience with Cochran fondly and profoundly, sharing a friendship and respect and often sending along special projects like asking for Cochran’s input on constructing mathematical models on spin generation during the implementation of the groove rule. He praised Cochran’s “endless curiosity.”

“Golf science has lost a pioneer, but maybe more than that, the way he went about it set a tone that I think has lasted. Certainly, if I am one of the modern practitioners, I feel a connection to what Alastair started, and I think I will be influenced by him, both professionally and personally, for a long time to come.”

At his core, Cochran, who played the game himself into his 90s and won a members’ competition at the R&A’s Autumn Meeting just last fall (his win came in the over-80s division but he also finished runner-up in the over-65s division with his uniquely assembled bag of six clubs), was simply a golfer looking for answers, like all of us. Unlike all of us, he found new clues in ground-breaking science to find those answers, sometimes decades ahead of his time. The search for him, though, wasn’t merely a matter of equations. He knew where finding ultimate improvement really would lead.

“If I may offer a personal opinion about the effect of technology on the game,” he wrote in the 40th anniversary edition of Search, “I believe it has been almost wholly beneficial. I do not feel the game is threatened by it. The laws of physics ensure that further performance improvements will be small and eventually limited. They will be genuine enough, however, to satisfy the golfer’s dream that the next product to hit the market might just be the magic club that transforms his or her game.

“Finally, I have to confess that in one sense nothing has changed for me since working on Search for the Perfect Swing. … I am still searching.”

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com