Editor’s Note: On Sept. 10, Arnold Palmer would have celebrated his 94th birthday. In honor of the occasion, we republished this interview with Palmer that first appeared in the January 2000 issue of Golf Digest.

At age 70, Arnold Palmer can’t wait until tomorrow, and it shows. One of the most important athletes of the 20th century, he may be the most visible and credible person in professional sports. And despite Palmer’s occasional protestations, his adoring public would clearly prefer to see him play mediocre golf instead of no golf. Go to any tournament, and you’ll see: Arnie’s Army lives.

Palmer is in constant demand, yet even when he’s on the road, his soul is at home in Latrobe, Pa., with wife, Winnie, who has been battling cancer. But Arnold is unfailingly gracious, if not somewhat reluctant to dwell on himself after all these decades. Palmer can laugh at his icon status, but the inflection in his voice turned serious when he discussed, with Senior Writer Bob Verdi, golf’s golden image and how it could be tarnished if those responsible for its growth aren’t careful. That’s the overriding message we gleaned from three sessions in his company. After all he has accomplished, Arnold Palmer still cares as much about golf as golf cares about him.

GOLF DIGEST: Even in this era of instant gratification, you and your background still impact all generations. Why?

ARNOLD PALMER: I know I like to think young. Maybe that has something to do with it. I’m not much for sitting around and thinking about the past or talking about the past. What does that accomplish? If I can give young people something to think about, like the future, that’s a better use of my time.

What concessions, if any, have you made to being 70?

Obviously I’m not playing as much golf. At least as much competitively. I probably have a club in my hands 360 days a year, one way or another, playing with friends or just fiddling around or hitting balls. But my schedule speaks for itself. I didn’t play that often on the senior tour last year.

You still love the act of hitting a golf ball?

Always. It’s always a challenge, particularly as you get older. Golf challenges you mentally at any age, and when you become my age, it’s a challenge physically to try to make your game work as well as it ever did. That’s close to impossible, but that doesn’t keep you from trying to hit the ball where you used to hit it and make the putts you used to make all the time.

Arnold Palmer’s timeless golf tips

As a senior, what skill goes first?

Distance. When you lose the ability to step up and hit the ball as hard and as far as you want, that also affects your ability to will the ball to go where you want it to go, if you know what I mean. The process has occurred over a period of years. It didn’t just happen, and I guess that’s one reason you keep trying to regain that knack of hitting a long drive on a par 5 so you can reach the green in two. That affects your entire game, and your confidence.

After all you’ve done, you experience crises of confidence?

Of course. But I also see some progress with my putter and my irons. That’s where I really fell off from where I used to be. I still have those times when I hit a 2-iron just right and it lands near the pin real soft, and I think to myself, “Oh, man, it’s back!” I can do that pretty well on the practice range.

You’re starting to sound like a lot of us now. If only you could take that game from the practice range to the course.

That’s what’s so fascinating about golf. And I’m still winning most of the skins in the games I play at Latrobe in the summer or Bay Hill in the winter. Pretty much the same group of friends. If I can take a skin off a 33-year-old guy who hits it for miles, you bet I enjoy that.

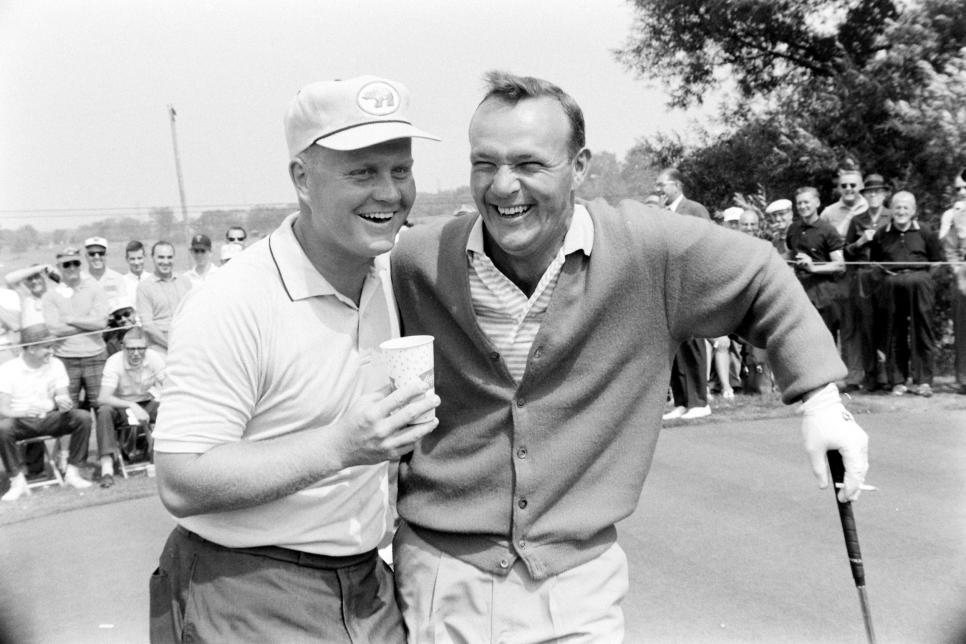

Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus smiling together in August 1963.

Francis Miller

Since you’ve turned 70, do you feel any different?

Sometimes, but most of the time, no. You can’t help but contemplate that you’re there. On the other hand, if you read the obituaries every day, you see that a lot of people haven’t made it. Every day I play golf, that’s my goal. To break 70 the other way. To shoot 70 or better.

When you see Gene Sarazen dying at 97, do you imagine yourself being as active as he was right until the end?

Without question, that would be a blessing. Gene was a great guy who had a wonderful life, and he enjoyed it thoroughly until he died.

You’re a long way from it, but could you see yourself as a ceremonial golfer, teeing off with the first group at the Masters every April, as Sarazen did for several years?

That’s something I really haven’t had to come to grips with yet, but I haven’t ruled out the possibility. As long as Augusta has the policy it has now for past champions coming back every year, and as long as I feel I’m not a nuisance there, I’ll play. When I think I’ve become a nuisance, I won’t play there anymore. I would go to the Masters; I just wouldn’t play.

After last year’s Masters, Mark Calcavecchia was critical of your participation and suggested it was time to hang it up. He later apologized profusely.

Mark wrote a very nice letter, and I acknowledged it. I think he was very sincere in his apology. Sometimes, in the heat of frustration, we all say things we wish we hadn’t said. I took it that he wasn’t mad at me but that he was mad at himself and mad at his game. I can understand that, believe me.

What is your definition of being “a nuisance”?

Not being able to contribute something to the tournament. As I said, I think I would always make an appearance. But as long as people want to see me play, I suppose I’ll play if I can. When I’m the only one out there, and nobody else is watching, then I won’t play.

It would be a cold day in Georgia when that happens.

I don’t know. I can’t answer that. I see things happening as I get older. I find myself getting associated with a lot of younger people in the game. I still enjoy playing with them, and I think they still enjoy playing with me. As long as I can stay competitive and have fun doing what I’m doing, I guess I’ll keep doing it.

You seem quite contemporary, even among players half your age.

Well, that’s part of what I mean. Not only being able to play a little bit, but still being able to relate. When I feel out of place, I’ll put the clubs away, get in a cart and just ride around and watch.

How else have you celebrated being 70 years old?

Well, I’m running again. Jogging around the golf course in Latrobe all summer. I feel better, and it’s better for me. As I told someone who asked me about my prostate problem, “I don’t have a problem—I don’t have a prostate.” I’m still at my desk most mornings, but I have scaled back a little. I used to get up at 4:30. Now it’s 5:30. Sleeping in.

To bed early?

Oooh, do I ever. Between 8:30 and 9 every night. Your wife, Winnie, chooses to be private about her battle with cancer. You went public with yours.

I did a public-service announcement. I’m not reluctant to talk about it. I would urge the government to allocate more funds toward fighting cancer. My own situation, it made me think. It made me think about the potential of dying. I wouldn’t say I was scared. I’m more scared of how it will happen than of it happening. I’m not scared that I’m going to die. I think of how I’m going to die. If I’m 97 and I have pneumonia and I die, then that’s appropriate. I don’t think Gene Sarazen would have had a problem with that. But I don’t want to linger. That scares me a little. The idea of lingering.

Being 70 means saying goodbye to some friends.

No question. I had to deal with the death of my roommate at Wake Forest, Bud Worsham, when I was in college. That’s a long time ago, but it devastated me, and I still wonder whether he’d be alive if I had gone with him to drive that night he died in the car accident. But now, you’re right. You see more and more contemporaries die. Frankly, I’m not much for funerals unless it’s absolutely an obligation. I don’t feel it serves much of a purpose to go and see my friends just lying there, dead. I try to pay my respects to my friends when they’re alive.

Arnold Palmer walking down the 18th fairway during hte second round of the 1994 PGA Championship.

Simon Bruty

What’s your schedule for next year?

After we get Winnie healthy again, I’ll continue to play, but I’ll also continue to cut back. I have Winnie to think about, as always. I have my daughter Amy’s son coming along, Sam Saunders. He’s 12. I have another one, Will, who’s 5.

Both those boys are potential golfers. Anyway, I’ll play the Bob Hope, a tradition. Bay Hill, hopefully. Augusta. The Senior Open, where Winnie and I are honorary chairpersons, at Saucon Valley in Pennsylvania, where her home was when I met her. I’ll play there. And I’ll play better than I did at the last Senior Open.

Which was in Des Moines. You shot 81-84, and it didn’t bother anybody.

It bothered me. But that tournament was one of the greatest examples of American style. Mid-America at its best. All of us were pleasantly surprised by how receptive they were to us.

You’re credited with getting the Senior PGA Tour on firm ground.

I don’t know about that. It took more people than me. And whatever I did on behalf of the senior tour was partly selfish, because I enjoyed playing golf too much when I turned 50…and still do…so it wasn’t like I was doing something I didn’t want to do or something I felt I had to do. The senior tour has been a tremendous success, and to a lesser degree than the regular tour, some players out there need to remember how things came to be what they are. The seniors, too, need to try harder to keep what they have.

What will determine where and when you play?

Oh, I suppose some of it will depend on how I feel or how I’m playing. Or, in an instance like last October, the Vantage tournament was at Winston-Salem, where I went to college and where I have a granddaughter at Wake Forest. At times, especially with Winnie back home, I felt very torn last year. I felt I should be there with her. But I also feel that golf is what I do and have always done, and just because you’re 70 years old, that’s no reason to sit in a rocking chair and say the hell with it and do nothing. That’s not right. That’s not me, anyway.

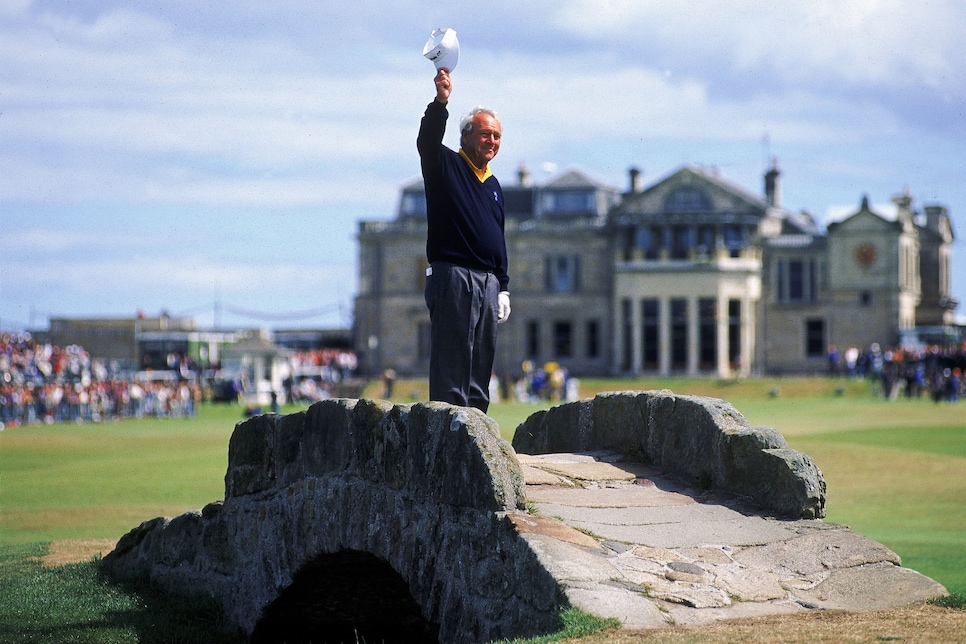

You said your goodbyes to the Open Championship at St. Andrews in 1995, and it was very emotional. You might go back this summer. But could anything be as emotional as your farewell at the U.S. Open in Oakmont in 1994?

Don’t think so. That was where I was raised. It was hot that week, I was tired, weak and I really broke up after it was all over. Terrible.

Arnold Palmer waves to the crowd from the Swilken Bridge on the 18th hole in his farewell at St. Andrews during the 1995 Open Championship.

Stephen Munday

Even when you go to Augusta now, you see not only people you’ve known for years, but their children. Fathers and grandfathers pointing to kids, “There’s Arnold Palmer.” Is that fairly intoxicating?

Absolutely. Plus, now I’m a member. How about that? A nice surprise. I enjoy the course, obviously, and the people. How much I’ll actually play there, I don’t know.

Talk about your purchase of Pebble Beach.

Very exciting. Pebble Beach is a national treasure, with the potential that it will remain much in demand. We plan to keep it special in every way. The people involved have a great feel for it. Yes, it’s an investment, but not a life-and-death investment. One of my closest friends, Dick Ferris, is the man who put it together. He mentioned it to me way back and asked me if I’d be interested. I said, absolutely. Then Peter Ueberroth came on. For a while, it looked like it wouldn’t happen. As we’re speaking, we haven’t even had our first real meeting yet, so I can’t answer specifically what our plans are, other than to improve it, wherever possible. Pebble Beach doesn’t need much tweaking, though, I don’t think.

You’re still doing big business.

We’ve had our setbacks, some of them significant. The automobile business, the golf company, but we’ve come back and recovered.

Arnold Palmer’s 10 rules for a golf life

Have these setbacks cost you, personally, a lot of money?

I’ve lost my share. But also, I’ve put a lot of time into certain projects, and let’s be honest, time is money. The time you spend on one aspect of your business is time you can’t spend on something else.

But almost every survey conducted about athletes and their wealth rates you at or near the top for credibility and cash. Why hasn’t money corrupted you? How come money hasn’t made you a bad guy?

Well, I don’t know what you mean by bad guy. I know I’ve had goals all along, and one of them was to provide my family with a lifestyle they deserve, one that’s comfortable. Plus, I have to keep working to keep that plane going.

Seriously? You have to keep working to afford your Citation X?

What if I want a new plane one of these days? I want to do that. And frankly, I like the idea of owning golf courses like Pebble Beach and Bay Hill and Latrobe. Not in a greedy way, I don’t think. But it is something I enjoy, and it does mean I’m being productive.

Leonard Kamsler/Popperfoto

And when you land your plane in Latrobe, it’s your airport.

Yes, they’ve named that for me. I’m proud of that.

Besides your airplanes, you haven’t indulged yourself with the other toys that athletes often acquire.

Ever since I bought and started flying an airplane, it’s been almost exclusively for business. I love to fly. It’s a great joy to me. But rarely do I use it for any kind of plea-sure, other than it is a pleasure to fly. The plane is like golf. They’re both my work, but I enjoy both thoroughly.

But you’re right. I don’t spend a lot of time fishing or boating or vacationing. It’s pretty much my family and my golf. And of course, the plane has allowed me to be with my family more often.

How many days do you wake up when you don’t want to see anybody?

I can’t remember the last one of those, but if there was one, I imagine I would just stay away. When I feel that might be coming on, I can go to one of my escape areas. The back room at my Latrobe office, to work on clubs, fiddle around. Been at Latrobe for almost 70 years. It’s warm, it’s quiet, it’s home. When it gets cold in October, we go to Orlando. But Latrobe is home.

Is it the roar of the crowd that keeps you playing golf?

Yes and no. Obviously, I enjoy playing in front of galleries. But I also can play golf by myself and thoroughly enjoy myself. Golf never ceases to be a challenge, even when it really is just you and the ball out there and nobody else.

Did you watch the recent Ryder Cup?

I was in Boston, in fact, while it was going on. But I didn’t go. I watched it, though, and I’m sorry for what happened with that Sunday celebration on the 17th green after Justin Leonard made the long putt. We have a great group of young men and a great group of golfers. I wish they were more aware of how the things they’re enjoying happened. I’m talking about the history and tradition. I wish they would show more appreciation for the opportunities they have. The celebration happened, and it was unfortunate, because the game was still on. Jose Maria Olazabal still had to putt. But our guys apologized, and maybe we’re making too much of it, particularly the Europeans.

We should be careful, though, because the whole world was watching, and we don’t want to let anything drag the golf itself down. Our guys showed great fortitude and talent, but I just wish they could have enjoyed it a little more quietly.

I’m all for rah-rah when you win. And the way they won was spectacular. But that putt by Justin Leonard, that didn’t win the Ryder Cup right there.

Arnold Palmer’s best golf courses

By seeking more mainstream sports fans, is golf in danger of attracting football crowds instead of the more traditional golf galleries?

What were there at Brookline, 50,000 people every day? That’s a lot, and they were as enthusiastic about the U.S. victory as the players themselves. But I would hate to think that we’ll have to start policing the galleries. That’s one thing we’ve always had in golf, galleries with a respect for the game. If the numbers become so large and the conduct so out of hand at events like the Ryder Cup, that would be the next step. Really policing the crowds.

You’re already on record as decrying any movement by Ryder Cup players to be compensated, either directly or so they may channel money to charities of their choice.

Yes, and that hasn’t changed. It’s ridiculous. If a player insists on being paid, I would skip him and go to the next man. If players, individually or as a group, want to ask questions of the PGA of America or the PGA Tour or any other organization, do it in the proper manner. Like I said before, settle problems from within. And remember, it’s for your country. The Ryder Cup is not an ordinary event. I don’t discourage players from asking questions, but if they don’t trust an organization, they should find out more about the organization. When Jack Nicklaus and I did what we did years ago about branching off into a PGA Tour, it wasn’t so much a knock on the PGA of America as it was creating a PGA Tour that could operate autonomously. And I think you’d have to say the PGA Tour has done well as a separate entity from the PGA of America. I also think the PGA of America and the PGA Tour, both of which have become quite wealthy, owe it to their players and the public to be careful how they handle their funds.

I am very much for—and this is not a selfish thing—pushing both organizations toward taking their retirement funds back, retroactively, to look after some of the players who need help. I am not going to name names, because I don’t want to embarrass anybody, but there are a number of older players who have contributed a lot to this sport. They played in a time when you couldn’t make all you needed in a short period of time, as is the case now, and I think it’s the responsibility of both organizations to address this situation. This is very bad, and we need to take care of these guys.

There have been lots of stories about you and Jack and how you were such rivals that there was never really that bond between the two of you. True?

That’s what they are, stories. Think about it. When I was 30, he was 20. That’s a big difference. Bigger than the difference between 50 and 40, or 60 and 50, I think. If being threatened is what causes rivalries, I never felt threatened, because I was older. As the years have gone on, the rivalry was more placid, if that’s the word. Jack came to me in the beginning and asked me to help him, and I did whatever I could. The rivalry has never gone away, either, but that’s the nature of the beast. It doesn’t mean we don’t like each other, and it certainly doesn’t mean we don’t admire each other. I certainly admire him.

I think we understood each other’s situation, almost to the point that you become protective of each other. But there’s never been a problem with our relationship. I’m on his Captains Club at Muirfield [Village], and I appreciate that. If I needed Jack for something, I’d call on him in a New York second. But when it comes to building a golf course or how we conduct our golf games, we are competitive. Nothing wrong with that.

Is Nicklaus the greatest player ever?

Certainly a contender for that, if not the greatest.

Who would be your top five?

I suppose I’d prefer not to do that. Without question, Byron Nelson would have to be up there. That’s about as far as I’d go. I admired Nelson’s game. Nelson, to me, made the golf ball do things and controlled it so well. And I don’t care if you’re playing in kindergarten, to win 11 tournaments in a row, never again. That’s unbelievable. Nicklaus, on the other hand, had the ability to just close himself off from everything. A great attribute.

Did Jack have better concentration than you?

Oh, yeah. He could just shut himself off and go play. I’m not sure I ever wanted to do that. And I don’t think you can just show up one week and do that. You can’t just say, “Oh, this is the U.S. Open, I’m going to do it now.” Especially me.

What about your relationship, or lack of one, with Ben Hogan?

Hogan was different. I didn’t know him that well, and maybe that was part of the problem. It’s not that I tried to force myself on him. I don’t do that with anybody. I played with him and against him and tried to be as nice as I could. But…

But?

He never called me by my first name. Never.

And Hogan looked right through you.

I suppose that’s the thing that bothered me some. That I was never an entity as far as he was concerned. I was just another player. I was on his team when he was captain of the Ryder Cup in 1967. But we never really had a conversation.

Another time, I played in an exhibition at Preston Trail. Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, Hogan and me. I played very well. I was low man that day, and I got the feeling that upset him. I talked to Nelson, I talked to Snead, but the conversation with Hogan was zero. I had more conversation with Valerie, his wife, a wonderful lady who’s gone now. A wonderful lady.

Arnold Palmer—The King for eternity

As the story goes, you buzzed the course in your jet before the 1967 matches, and Hogan wasn’t amused.

Well, it’s true about the plane. But I didn’t think it was that big a deal.

Is that why Hogan didn’t play you in the second morning four-balls?

Because I took a ride in my jet over the golf course? I don’t think so.

Would it be safe to say that Hogan didn’t enjoy golf as much as you?

Oh, that’s not my place to say. He was driven, determined to do something and he did it. I wouldn’t begin to guess what went on in his mind or what his bottom line was. Only thing I know was that Jackie Burke and Jimmy Demaret had a good relationship with Hogan, and I discussed Hogan with them. They just said, “That’s the way he is.”

Did anybody have as much fun as you?

If they did, they had a hell of a time.

En route to your first major victory, the 1958 Masters, you received a favorable ruling on the 12th hole in the final round. Ken Venturi, who was in contention, didn’t take kindly to it. Has that affected your relationship with him?

I don’t think so. Kenny and I are friends. You say it was a favorable ruling; it was the correct ruling. The ball was embedded and we were playing wet-weather rules. I wound up hitting a provisional, and the tournament committee ruled accordingly. That, incidentally, is the same hole where I had a chance to win [in 1959] and staggered with a triple bogey. Venturi was a victim of my success in 1958, just as I could say I was a victim of his success at the ’64 Open, which he won and where I had a chance. I certainly don’t hold it against Julius Boros, because he kicked my ass a few times. Or Billy Casper at the 1966 Open. Or any of the other guys who beat me. You lose more than you win at this game. A lot more than you win.

Where is golf headed in the next 10, 20 years?

I don’t think there’s much need for change. Not only is golf growing over here, it’s growing everywhere. All the tours in other countries are growing. We have to be careful of technology, and that to me means slowing down the ball. We don’t want Winged Foot, Oakmont, Medinah, Olympic to become obsolete. I really think you can get all the manufacturers to take 10 percent off the ball without having a bunch of lawsuits. I don’t think it’s that big a deal. What a shame that would be if all those great golf courses couldn’t be played because of equipment.

Beyond that, with all the new people coming into golf, I’d like to see all of golf’s organizations launch a program, whether it’s through seminars or films or whatever, that teaches more about what the game is all about, its history and tradition of integrity. Every organization should get behind this, and every individual golfer. Every 20-handicapper who goes to the first tee with a knowledge of the game should pass it on to someone who doesn’t know, or doesn’t care. For every swing lesson a golfer takes, take a lesson in rules and etiquette. Preserve what we have. Is Tiger Woods versus David Duval on prime-time television a good thing for golf? I see nothing wrong with it. First of all, made-for-TV matches have been going on for some time, such as the original “Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf.” The Woods-Duval match last summer is something to keep an eye on. Prime time is an area that really wasn’t associated with golf until The Golf Channel came along.

Is there a danger of superstars such as Woods and Duval becoming a league of their own?

I’ve thought about that, and my answer is that it would have been far more likely 30 years ago. There are more players now, more good players. For instance, if Jack, Gary Player and I had gone off to do our own thing when we were playing our best golf, it could have been a tough time for golf. It could have delayed the dramatic growth of the game that we now see. Tiger and Duval are fantastic, no doubt about it. But there are so many other players out there, good stories we haven’t heard about.

Speaking of The Golf Channel, that’s an investment that has to make you proud.

A wonderful story. People ask me whether I’m surprised that there’s a demand for an outlet that has only golf 24 hours a day, and I must say, yes. I wasn’t smart enough to plan on that. I was watching one of those shoot-’em-up westerns on TV just this morning. It wasn’t very good, and I said so to Winnie. She said, “Well, why don’t you just turn on The Golf Channel?” Pleased the hell out of me, that Winnie would say that. And I did. Joe Gibbs [Golf Channel cofounder] was unbelievable with his foresight and thinking, and he had a lot to do with convincing me that it would work. I thought it was a tremendous idea, but I also had some skepticism. I mean, 24 hours of programming is quite an undertaking. I was the one who said to Joe, “What about this?” and “How are we going to do that?” And that’s just what he was looking for, I guess. Someone to toss out potential ideas, as well as potential problems.

We had hours and hours of meetings planning The Golf Channel before we started raising funds. I still call Joe, who’s the president and CEO. I’m still chairman, and we talk a lot. He’s done a wonderful job. We cover a lot of instruction. We have shows on architecture, although I think we could do more. And we’ve certainly raised the profile of the European tour with our telecasts of their events. I think we could also do more propaganda, about protecting the game. You know, integrity, tradition. We’re at about 26 million households as of the end of 1999. That’s a lot of people, and many of them are being introduced to the game.

You were the man most credited with making golf so popular on TV and building the foundation that now exists.

That’s nice of you to say, and it is you who said it. What I would say is that I never considered it a chore to deal with the public and the media. Hey, if you want to be a good player, in any sport, you have to respond.

Or else…

Or else. Well, I hope everyone involved now understands that this could all go away. I hate to even go on the record with that, because I don’t think it will happen. But everything that has helped make this game as popular as it is now—the sponsors, the media, the public, the volunteers—they could all go away if they don’t like what they see in golf. We have this image, this reality, that makes golf distinct. We have been incredibly fortunate to keep things the way they are. I mean, if Tiger Woods slamming his club into the ground is the biggest worry we have, our sport is in pretty good shape. That’s not really all that serious, somebody like Tiger showing his emotion. That’s not what I would call poor behavior, especially compared with what’s going on in other sports.

What part have you played in golf’s modern code of conduct?

I don’t know that I’ve done anything but learn from the people who came before me and tried to pass that on to people who come after.

OK, let’s go about it this way. What if you had been as great a player, but also a jerk?

You mean I’m not? [Laughs.] I suppose it wouldn’t have helped if I wasn’t as comfortable around people as I am. Everybody who has played golf on the PGA Tour hasn’t been a great guy or a role model, but we’ve managed to keep the bad stuff out of the headlines. It just seems to come with the territory. When my father, Deacon, started out in golf, his knowledge was zip. But he had good people teaching him the right things, and he passed those lessons on to me, and I’ve tried to do the same.

Before you understood what your father was all about, though, you mistook his approach, didn’t you?

All the time. I could never quite understand why he wasn’t throwing more accolades my way for all the wonderful things I thought I was doing. I know better now. He didn’t want to puff me up too full of myself. More importantly, he didn’t want me to ever think golf would be an easy road. He was right. It hasn’t been easy. Fun, but not easy.

10 rules for fearless golf from Arnold Palmer

If you had spent less time concerning yourself with the other side of the ropes, if you had had more tunnel vision about your game, would you have won more?

Perhaps. I think I know what you mean, but I want to make sure. You mean if I had gone to hit balls after every round instead of mingling with sponsors and fans and you guys in the media?

Exactly.

Well, I couldn’t have enjoyed it more than I did if I had devoted more time to my golf itself. If golf itself had been all that mattered, I can’t imagine I would have had a better time, even if I had more trophies. Sure, I would love to have won the four Opens I almost won, or the two or three PGAs I barely lost. But, if I had it to do over again, would I take a different approach? I wouldn’t. Let’s say I could start over. I could have five Opens and two PGAs and six Masters and a couple more British Opens, but not as many friends? No. No way, Jose. Keep the trophies. I mean, I remember teeing off in Palm Springs at the Bob Hope and because I had a couple of bad rounds, I’m starting early. Real early in the morning. Maybe 7 o’clock. And here comes “Arnie’s Army” in their pajamas and robes at the first tee.

Tiger and Palmer became friends over the years.

David Cannon

You didn’t just wave, either.

No, at some of these places like the Hope and Augusta, I not only got to know my fans, but their children, and then the grandchildren. You should see the letters I get from people. All the time. “Dear Abby” letters. People telling me their problems, sharing their lives with me. Really personal stuff. There’s a retired Army colonel, not a week goes by when we don’t hear from him.

Are you worried about passing the baton to golf’s young?

They already have it.

Do you pass it with trepidation?

With words of extreme caution. Protect what you have. Think of those who came before, think of those who are coming next, like your children. An athlete must have a certain cockiness to succeed and win, but an athlete must also care about the game he or she plays. The conduct in other sports is getting worse, and what bothers me is that people are beginning to accept it—”Nothing surprises me anymore.” How many times do you hear fans say that about the sports they follow? Well, that’s discouraging. I don’t think we’re at that point in golf, and I hope we never get there. The drugs now in other sports. You pick up the paper and read about these guys using dope. I don’t understand it.

What about John Daly?

I know him a little bit, and I see where he says he’s drinking again because he’s tried doing everything—like staying sober—for everyone else. I don’t know all that’s going on there, but if I were to talk to a John Daly, I would say that if he were to do one thing for himself and only himself, it would be to not drink.

I’ll give you an example. If I had known what cigarettes were doing to me, regardless of what other people might have been saying about my smoking, I would have quit sooner than I did. I quit smoking on the golf course 38 years ago, 30 years ago completely. Jack used to smoke, Lee Trevino, too. When I see some of the old film clips and see how I silly I am with that thing hanging out of my mouth, how obnoxious I looked, I could just cringe. My father tried to convince me of that when I was younger, but like all kids, I knew more than he did. Fortunately, I could see and feel for myself what those things were doing to me. I can run now at 70 better than I did 40 years ago, when I huffed and puffed.

Any pet peeves about golf?

Yeah, guys who don’t take their hats off indoors. It’s a matter of courtesy. You don’t need to protect your head from sun or wind or rain indoors. End of story.

What about slow play? The Americans noticed it in the Europeans during the Ryder Cup.

Slow play is more inconsiderate than anything else, especially if it’s intended, which in some cases it can be by one player or one group. I can’t really say for sure that it has been done to me for a purpose. Jack was always slow, but he didn’t do it because of his opponent, he did it for himself. That’s just the way he played. Me, I’m the other way. I like to move, in golf and in every other thing. I like to go fast, particularly in my plane. I got where I got—wherever that is—by doing it my way. I was maybe too aggressive in certain instances, and maybe it cost me some tournaments. Jack was maybe too conservative, and maybe it cost him a few. But you are what you are. I never mimicked anybody. That was the real me. I wasn’t perfect, and never intended to be.

David Cannon

As long as we’re discussing things that annoy you, a little birdie told us you weren’t thrilled that Golf Digest’s ranking of America’s 100 Greatest Courses wasn’t too kind toward those designed by you? Care to vent?

Well, I do have an opinion about that. Any magazine or any publication is entitled to do that. Just as any writer has a right to take a shot at a golf course, or at me. Not all the people in my design company share that view, but that’s how I feel.

Besides, maybe I’ll start my own ranking. Maybe we’ll have the top 100 courses in the world as ranked by The Golf Channel. [Laughs.] Even when my own people say, “Why don’t we do more to get our courses into the top 100?” I think back to what my Dad used to say: “Just keep doing what you’re doing, and if you’re good enough, they’ll notice you.” Once again, he was right.

Ed Seay, who has been with us for many years, is very good at what he does. I’m perfectly happy with where our golf courses are, and we must be doing something right. We’ve designed more than 250 courses around the world, and we have contracts for more than 60 on the table right now. Bay Hill is a great golf course. I think Spring Island, a course we built in South Carolina a few years ago, is a great golf course. But what does it take for a golf course to get attention? You’ve seen architects start out wanting to create the most spectacular course ever, the most difficult ever, the only one of its kind. Eventually, though, you might see these same architects soften a bit and try to build more playable courses, which is how we started. That’s been our objective all along, to build golf courses for golfers, not for ourselves and not for the rankings.

You and Jack Nicklaus are building a course for the World Golf Village in St. Augustine, Fla., The King The Bear. How are you going to handle that? Will you build one nine and Jack the other?

No, I think we’ll collaborate on all 18. What that means, I suppose, is that I’ll go in there and do something. Then, Jack will follow me in and change it. Then I’ll go back in and change it back. Maybe it will never get built. [Laughs.]

Let’s get back to your game. Would you change anything in your me-chanics if you were starting over?

Well, it’s been said my swing isn’t something you’d necessarily teach, because it’s not the most picturesque. But it was mine and still is. Nobody has tried to change it. The only change I’ve made over the course of time was with my left hand. I do think I would seriously consider putting cross-handed if I had to do it all over again. I tried it many years ago at the British Open and shot 31 for nine. The next day, I went back to the conventional way. Mark McCormack was there and said, “God, you putted so well the other way, why did you go back to the old way?” Good question. I had been struggling the old way, so I changed on the 10th green and then put up 31. I would give it a hard look now if I were starting, but it’s too late for me now.

You mentioned Mark McCormack, the founder of International Management Group that you joined 40 years ago. You wrote in your book, A Golfer’s Life, about a couple of times when you considered severing relations.

I don’t know that I really thought of breaking away from IMG. If you don’t have some differences of opinion in a business relationship over that span of time, something would be wrong. We still have a pretty good relationship. Mark and I get together socially on occasion and still talk business once in a while. But there’s no question we were good for each other. Time proved that.

Why aren’t you grumpy and down on life, like a lot of other 70-year-olds?

I have too many other things to do. My dad surprised me when he said he was going to retire. He was 68, and I couldn’t get it. A lot of people work all their lives to get in a position to do something else that they enjoy. I totally understand that. I would be the same. Luckily I’m doing something I love, still. I mean, if I quit what I’m doing tomorrow, what would I do the next day? Play golf, or fly, or both.

The only visible concession to age is your hearing aids.

But I’ve had them since I was 42 or 43. It’s in the family. It’s in the genes. My grandfather lived to 100 and wore hearing aids for 55 years. My doctor, meanwhile, told me my eyes are those of a 25-year-old, my heart’s good, my cholesterol is good, and like I said when somebody asked me about my prostate problem the other day, “I don’t have a problem—I don’t have a prostate.” Nothing I can’t do. When I have too much wine one night, I still feel it the next day, just like I always did.

What about your late-night TV career?

You mean when I was guest host of “The Tonight Show” a long time ago? Spiro Agnew was vice president of the United States, and he was a guest. So was Vic Damone. For a one-night stand, sitting in for Johnny Carson, I wasn’t bad. I started with a few lines, not really a monologue. I’m not funny in that way. Not a stand-up comedian. I was nervous, though. I could do it now a lot easier, because I’m more confident, more relaxed.

You were also pointed toward a movie career.

I don’t know about “career.” Jay Michaels was an associate of Mark’s and mine, and I told him way back I’d like to be in a western. I watch them all the time. And I still read westerns. Zane Gray, Louis L’Amour.

Arnold Palmer swing sequence

Who did you want to be, John Wayne?

Hell, no, I wanted to be me. “Northwest Passage” always stuck with me, because Spencer Tracy reminded me of my father. Anyway, I wanted to ride horses and sing songs and shoot the bad guys and do whatever the script called for. People have sent me scripts, you know. Anyway, Jay up and died on me, and there went my movie career.

What would you have done if you weren’t a golfer? A politician? There was some talk of that, wasn’t there?

Some talk, yes, but I don’t think so. I might have been an artist, a painter, believe it or not. My first-grade school teacher, Rita Taylor, told me I had some artistic talents. I drew a little in school. If I hadn’t been a golfer, I’d have probably painted, ooh, I don’t know, country scenes. When I design a course, I draw a lot of golf holes. My stuff is pretty rough. Winnie goes to a lot of museums and she has a lot of paintings. I have an eye out for good art, but I wouldn’t say I’m an expert or a collector. Winnie is.

So, now, you’re announcing here for the first time ever that if you had not been a professional golfer, you would have been an artist?

No, I would have been an airplane pilot who drew on the side. As a hobby.

When you hear yourself referred to as “The King,” what’s your reaction? I’ve laughed about it, kidded about it. People have used the term as a fun thing, and I appreciate it because I think I know where people are coming from. Everybody has a different definition of what it means, and my definition is that there’s no king in golf. Certainly not me. And I’ve taken more from this game than I’ve given.

AP Photo

But you’re a legend, and we’re here to give you a mulligan. For any shot or tournament that haunts you.

Haunt is not the right word. I’ve had disappointments, but they don’t haunt me. There was the 1966 U.S. Open at the Olympic Club, where I had a seven-shot lead with nine holes to go. A lot of things got in the way. I had a chance at the Open record for scoring. Also, at Olympic, Billy Casper—we’ve always been friends—walked over to me there and said, “Gosh, if I don’t play better, Jack’s gonna beat me out for second.” I said, “Well, if I can help, I will.” That’s where the roof fell in for me. Sure enough, he caught me and beat me for first in a playoff [69-73].

The other incident was at Augusta in 1961, and similar. I lost track of what I was doing. George Low called me over to the ropes on No. 18 on Sunday and said, “Great going!” and I let down. I shook hands with him and crumbled. I double bogeyed the last hole. You can’t do that. You let up. It’s subconscious, but it happens.

There have been a few others. I would have loved to have won an Open at Pebble Beach, which I thought I was going to do. And I suppose if there’s one thing missing from my career, it’s the PGA Championship. I had my chances but it never happened. If I could crank it up for one more week and go out and win one, that would be nice. But I know that’s out of the question.

Why are you smiling like that?

At least, I think it’s out of the question.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com