Stressed from unrealistic expectations, long hours and being micro-managed, superintendents and turf managers are leaving the golf industry for all the wrong reasons. Along with relatively low pay for apprentice greenkeepers and qualified turf professionals, it is the most concerning issue in our game.

Droughts, bushfires and flooding rains have wreaked havoc on Australia’s eastern seaboard during the past five years. Golf clubs have borne the brunt of the recent ‘big wet’ that has left courses waterlogged for months on end.

Superintendents and turf managers have never been under more pressure from their clubs to get golf courses back open for play. It’s mentally distressing to finally get their flood-ravaged courses playable only for another rain event to force closure.

Statistically through COVID, there’s been an increase in numbers of people wanting to play golf. So it’s a double whammy with more rounds played and terrible weather in order to try to produce quality surfaces with the additional ‘wear and tear’.

It’s been a very challenging period to navigate. But while ‘Mother Nature’ has been cause for concern, Australia’s extreme weather events have tended to mask serious problems in the turf-management industry.

Increasingly, superintendents have been resigning – or had their employment terminated – after many years of unstinting service. They’ve dealt with droughts and flooding rains. But it’s golf-club management that is the bane of their existence; people without formal qualifications in turf wanting to ‘micro-manage’ the actions and decision-making of the superintendent.

Furthermore, young people aren’t entering greenkeeping in sufficient numbers. Golf-course maintenance has traditionally been one of the lowest paid trades. These days, kids want a well-paid job straight out of school and aren’t willing to do the hard graft like previous generations.

It’s come to a head this year with the turf industry rocked by the deaths of two men to suicide: a superintendent and a turf-equipment technician both at their respective golf courses. That’s a horrible state of affairs considering golf is a recreational sport.

Overworked, unappreciated and stressed out

A former superintendent of more than 20 years quit because of health reasons brought upon by stress. The former super confesses he was a ‘mess’ when he resigned, forgoing a salary of more than $200,000 per annum.

Without going into detail that would reveal his identity or the golf club, he faced issues with regard to course presentation. Yet it was seen by club hierarchy as a major issue for a course usually presented in pristine condition all year round.

“It was putting me under a lot of stress. I think most superintendents take a great deal of pride in their work and that really affected me,” says the former super. “I was as committed as anybody to their job. The impact on my family’s life and social life on weekends through summer… going in to check greens for God’s sake! And then feeling guilty if I had any sort of time off. It’s crazy.”

Now working on the fringe of the golf industry, he knows of at least 15 other superintendents who left their jobs purely because of stress from dealing with golf club committees and general managers. He describes it as a dire situation as golf is relinquishing so much knowledge and dedication. Increasingly, apprentices will be elevated to senior roles without the benefit of that knowledge.

“The industry is losing all this great experience: people managers, project managers, all the agronomics. And it’s a really bad situation,” he adds. “Basically, I left because I was burnt out. It was a seven-day a week job for me. And that’s the same for a lot of superintendents.”

The hours can be horrendous. Most superintendents start work about 5.30am. An early finish would be 3pm. However, committee members tend to set meetings after 4pm when they have finished work. They don’t consider the poor super has had a really long day and faces another early start the next morning.

People management is a challenge. It’s not an easy task to try to motivate young people to turn up, do a good job and take pride in their work. Superintendents run the biggest staff at a golf club (with the exception of food and beverage at Royal Sydney or a private club on the Melbourne Sandbelt).

Furthermore, there is more workplace health and safety (WHS) implementation on a golf course than inside a clubhouse. Turf managers are also burdened by environmental legislation. But it’s the club system that causes the most stress.

“Committees at most clubs are just unbearable. That’s why superintendents are leaving,” says the former super. “I just couldn’t work with one of the committee people. He wasn’t a nasty person. He was just a control freak who thought he knew more about the things that were required than what I did.

“I felt like I was losing control. I would have to ring him and run things by him because he was just so interfering. I couldn’t do anything without him having a say. It was unworkable. I was vomiting before work for four or five years from stress. I was a mess. My wife actually caught me in the shower having a bit of a vomit before work one morning. This was right towards the end. And she said, ‘That’s it. You’re resigning tomorrow. No more.’

“I didn’t have a job to go to or anything. And you know what? Best decision I ever made.”

Such was the esteem in which this turf manager was regarded that he would frequently field calls from stressed superintendents, asking for advice on dealing with committees and management. And he would phone to see how they were doing – in the tone of, ‘Are you OK?’

“At the same time I was too scared to tell them I was going through it as well,” says the former super. “There’s a lot of people going through it. A lot of people have had enough.”

For example, a superintendent at a northern New South Wales club resigned this year due to the combined stress of dealing with a severely weather-affected course and unrealistic expectations about its condition from the committee. Another super gone with 25 years of experience.

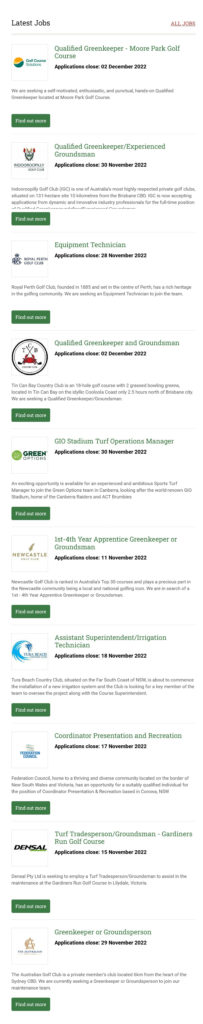

A snapshot of what is a lengthy list of vacant positions in the turf industry across Australia.

Turning their back on the city life

A lack of proper financial remuneration, broken promises and being micro-managed were reasons why a turf manager quit two superintendent roles at Sydney golf clubs in the space of eight months.

Trying to raise a young family in Sydney is difficult at the best of times. But it was problematical as a rental tenant with three children aged under 12 – even though the super’s wife had a full-time job managing an international fast-food franchise.

In three years at the first club, this super had achieved outstanding results with a maintenance crew of just six greenkeeping staff. This period coincided with severe water restrictions. After starting his day at 5.30am, the super would often return to the course about 5pm to hand-water greens. He routinely put in 50-plus-hour weeks during summer.

His starting salary of $60,000 had been increased by $5,000 after six months as written into an employment contract. But the long hours eventually took its toll and further requests to be compensated were met with deaf ears. The club continually blocked his wish for a modest $5,000 pay rise. Literally, $100 extra per week would have been enough to keep him.

“The expectations always grew but the salary never did,” he says. “Back in the day we were just growing grass. We’re agronomists now and we’ve got all these other hats that we need to wear. Work health and safety. Preparing budgets. There’s a lot more involved these days than there was 30 years ago.”

With the first club’s course masterplan going nowhere, he handed in his resignation to take up another superintendent role on the other side of Sydney. The lead role at the second club came with financial remuneration of $75,000.

A number of course improvements were quickly made in the first six months from his fresh set of eyes. The general manager promised the world and he got on well with the board.

However, the maintenance budget was mediocre at $800,000 per annum (including wages of eight full-time staff). The capital expenditure budget was satisfactory, but he wanted more money to spend on general items to maintain the course. After six months he submitted a request for a 2.5 percent maintenance increase. The GM knocked back the $15,000-$20,000 rise.

The super’s work ethic never wavered despite the additional burden of a 90-minute daily commute across Sydney to the second club. Instead, it was excessive supervision by the GM that eventually took its toll. Members were blindsided when the super handed in his resignation.

“It was more so having a general manager that was trying to micro-manage everything that I did. That was one of the big reasons, as well as budgets,” he says. “The general manager didn’t like me coming in and having my two bobs worth. And that’s what they employed me to do.” Incidentally, the general manager “got rissoled” two months after the super’s departure.

Fortunately, the super now in his fifties wasn’t lost to the golf industry. He sought a “sea change” and relocated his young family to regional Australia where he’s been superintendent at a progressive club. And the astute club has recognised his value with a six-figure salary – $40,000 per year more than he was receiving at that first Sydney club.

Turf managers treated like dirt

A former superintendent was asked to resign from a prestigious capital-city golf club. The super had suffered a personal tragedy shortly beforehand and he felt the club used that as a catalyst to change to a different direction.

It was a humiliating experience for a man who became a superintendent at an early age. He managed some of the finest golf courses in Australia and prepared some of our premier tournament venues during his time as a turf manager.

“People who have been in the industry a long time just get treated like a bit of dirt in the end,” says the former super who now works as a consultant and project manager.

Like other superintendents, he suffered from high expectations, being pushed too hard, along with a lack of understanding, especially from committee members that tend to be “retired people who still want to have power. They’re all experts in Googling”.

“Myself and all of that have all been pushed out. Because the older you get, they find that you’re a threat to the committee,” says the former super who decided to ‘resign’ after feeling burnt out and having lost the passion for a job with a salary of more than $150,000 per annum.

“[They] will end up employing a young kid for $80,000, $100,000, and think [they’re] doing all right. [They] can dictate to him and tell him what to do. But when it all goes belly-up, [they’ll] blame the s–t out of him. Then the poor kid’s destroyed for the rest of his life. And that’s why they’re all getting out of it.”

Job vacancies for turf managers are at an all-time high, judging by positions advertised on the website for the Australian Sports Turf Managers Association. More than 50 jobs are currently listed on the association’s website whereas there were 20 at the very most pre-COVID.

Wealthy private clubs have the capacity to headhunt the best talent available. But as a result, less fashionable clubs with smaller budgets are finding it more difficult to find turf managers. That’s been exacerbated by heavy rain events that have beset Australia’s east coast during the past two years.

“I do believe we’re in a crisis,” says the consultant. “Have a look at all the ads. In Melbourne, I’ve noticed super jobs that have been there for months and months. I’m not talking about the inner-city ones, I’m talking about those lesser-type, out-of-city clubs still looking for a superintendent.

“I’ve seen a lot of trade, grade 3 and assistant jobs coming up. I think a lot of assistants are probably waking up to the situation now that this job’s not what it’s all made out to be. They can make more money in the mining industry. Or guys are going to work in the sales industry.”

“I predicted 15-20 years ago that there will be a crisis. Just the way the committees and managers were starting to treat guys. I know the money got to a reasonable point for a lot of guys in the end. But now with money being tighter for certain things, supers are not getting the same salary packages that, say, a general manager does.

“Royal Melbourne and The Australian are always going to find the best super and they’ll pay the best. But I think for this next tier down it’s going to be a real problem.”

Spending more time with family

Young turf managers are being lost to the golf industry for various reasons. One aspiring superintendent left for the opportunity to start his own fencing business in a capital-city growth corridor.

The third-generation greenkeeper had finished school at 16 to become an apprentice under his uncle at a nine-hole municipal course in Sydney. He completed a trade at TAFE, a Certificate 4 and a Diploma in Sports Turf Management. Over 16 years, he rose to the position of 3IC during stints at two Sydney courses. But the financial rewards didn’t seem to justify working 52 hours a week. Disillusioned, he quit the industry to start the fencing business. The most appealing aspect for the now 36-year-old was the flexibility to be his own boss and work his own hours.

Along with his wife (who works two days a week as a permanent casual), their combined income is similar to what he used to earn as a turf manager. The flexibility allows them to take a three-week family holiday around New Year with their two children (aged 9 and 3).

Other advantages, like running two motor vehicles in his company name, outweigh the disadvantages, such as the lack of a steady weekly wage.

“I had a younger family so trying to spend time with them,” he says about the primary reason for leaving the golf industry. “I was missing out on a lot of stuff as well. Family holidays. Christmas. Summertime is obviously the biggest time of the year [for a turf manager].”

As a low handicapper with attention to detail, mistakes by his work colleagues would lead to dissatisfaction. For instance, turning up to play a Monthly Medal round only to discover a greenkeeper (who wasn’t a golfer) had placed tee markers so close to hedging that it was impossible to generate a proper backswing.

“Money? Not so much as the loss of passion for it. I found myself getting more and more frustrated with things. Like any job, you get to the point where you change what you’re doing.”

Australian superintendents revered around the world

The perception of turf managers wasn’t helped by Bill Murray’s portrayal of mentally unstable greenkeeper Carl Spackler in the film “Caddyshack”. The reality is quite different. From a formal education pathway, an Australian superintendent will have completed a four-year apprenticeship (including three years of TAFE study to acquire a Diploma in Sports Turf Management). Some will also undertake a Bachelor of Agriculture and Technology, majoring in Sports Turf Management.

It’s very different to what happens in America where aspirants will undertake a college degree for three years before entering the workforce. “That’s why Aussie greenkeepers are so sought after – because they learn the practical stuff first and learn on the job,” says Brett Robinson, editor of Australian Turfgrass Management Journal.

Indeed, what makes the treatment of our superintendents so baffling is how extremely well regarded they are internationally for their knowledge and willingness to roll up their sleeves.

“You only have to look at the numbers that have worked over in the Middle East, the US and right up through Asia. It comes back to having that practical experience in their younger years, whether it be through construction or general course maintenance. They’re very practical people, very astute and their work ethic exemplary,” Robinson adds.

“Internship programs through Ohio State University, they always cry out for young Aussie greenkeepers because they know that they can place them easily. Put them on anything and they’ll be able to do anything straight off the bat. You don’t have to train them up. And that flows onto the more experienced guys, too.”

The danger for the Australian golf industry is that turf managers have multiple options. During the mining boom, some left to be fly-in/fly-out workers. Today, they can work in sportsfield and racecourse management – anywhere with more money that’s less stressful. Even a job on the parks/gardens maintenance crew at the local council tends to pay more without the awkward hours.

Given the tight labour market, clubs need to be mindful of how they treat course-maintenance staff. Give them a bit of incentive in terms of working conditions or extra pay above the award wage. Because clubs can train up an apprentice for three years and see them leave for a job with better remuneration, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne where rental prices are exorbitant.

Right in the firing line

Historically, golf clubs are run by volunteers. As such, there are power plays between committee members and general managers. Unfortunately, the poor superintendent is usually in the firing line most of the time and an easy scapegoat.

It’s all very well for Golf Australia to instigate campaigns to make the sport more inclusive for women, juniors and those physically challenged. The national governing body is obligated to draw more people towards golf. But in doing so, it appears oblivious to the crisis facing golf in Australia.

Alarm bells should be ringing. We simply don’t have enough experienced superintendents and qualified turf managers to maintain courses to the expectations of members accustomed to seeing PGA Tour-quality surfaces on TV.

Expectations need to be lowered: sometimes a golf course’s conditioning is beyond the superintendent’s control: wind, rain, extreme heat, drought, flood and fire. And every course is ‘site specific’ with regard to microclimate, water forces, turf variety and soil types. The superintendent is most prepared to know how to deal with those little idiosyncrasies and manage them in the best way with the available resources.

Creating a more harmonious working environment for golf-course superintendents and turf managers is no easy fix.

“There has to be some overriding guidebook as to what is a committee’s responsibility and jurisdiction. You can’t give a superintendent the responsibility of managing a course without giving him the authority,” says the former super now on the fringe of the industry.

“Then there’s that sort of mixed message of a committee taking the credit for all the things that go well

but they don’t take the blame when things go [pear shaped]. They just haul the superintendent over the coals about things.”

Need to talk to someone?

Don’t go it alone. Please reach out for help.

Lifeline: 13 11 14 or lifeline.org.au

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636 or beyondblue.org.au