(That and five other golf myths debunked)

Golf has always been up for a bit of folklore and storytelling. Whether it’s a leathery teaching pro passing on swing wisdom to an eager apprentice, a playing legend recounting exploits from decades gone by, or an architect creating a golf hole from divine inspiration, all of it adds to the game’s mystical appeal. It’s a common thread that goes back to the shepherds who first banged rocks across a damp Scottish moor.

Of course, facts have usually never gotten in the way of a good story. Some of the most widespread “truths” in this game have turned out to be much more myth than reality – sticking around for decades thanks to the credentials, charisma and persuasiveness of the storytellers. Thanks to a more widespread grasp of physics – and less reliance on anecdotes and second-hand accounts – we can now gently dispel some of the more durable beliefs and habits that have embedded themselves in the game’s lexicon.

On the following pages, we’ll explore six of the most pervasive fables and have experts explain why they might sound right but are far from it. Apologies if you’ve lived by these notions for most of your golf-playing life, but it’s time to realise that the world is round, lightning can strike in the same place twice and a groundhog can’t predict the seasons.

Keep your lucky ball marker if it makes you feel better, but don’t be surprised if you get some funny looks the next time you trot out one of these outdated chestnuts.

Determining wind direction with grass blades can fool you

It has become a televised golf ritual: a player and his or her caddie throw some blades of grass and look thoughtfully at the trees around them – or the flag on an adjacent hole, like at Augusta National – to try to divine how the wind will affect the next shot.

It might be good theatre – or a way to calm the nerves – but it turns out that the information gleaned from it isn’t particularly accurate. Just ask somebody who relies even more heavily on wind direction to win than golfers do. Nick von der Wense is a 15-time American sailing champion with experience racing everywhere from the open ocean to the lakes of Minnesota.

“Making your strategic decisions based on what you feel on the side of your face is a recipe for losing,” says von der Wense, who has raced everything from single-sailor Lasers to 80-foot-mast yachts.

“What you feel down by you can be, and usually is, very different than what’s happening 20 feet or 100 feet above the ground.”

Surface wind is impacted by everything from the colour and temperature of the ground, barriers like trees blocking or channelling gusts and the prevailing wind direction that day.

“Your best bet is to look at the flag on the clubhouse; think of that as the prevailing wind and make your big-picture strategic decisions accordingly,” von der Wense says. “The more difference there is between the temperature of the ground and the air temperature, the windier it’s going to be. When it gets calm and awesome on the golf course at the end of a late spring afternoon, that’s when the ground and air temperatures have equalised.”

Under specific conditions – think of a hole at New South Wales Golf Club with nothing between you and the Pacific Ocean – throwing grass might work, von der Wense says. But our advice? You’re better served by choosing your shot, committing to it, and not clouding your process with what is probably a bad read.

No, your putts don’t always break towards

It’s one of the oldest myths in golf broadcasting: playing in Palm Springs, they say that all putts break towards the town of Indio. At Pebble Beach, you’ll hear they break towards Carmel Bay. Golf-course architect Bobby Weed has heard them all – even about the courses he has designed, such as TPC Summerlin in Las Vegas.

“There they claim everything breaks towards the Strip,” Weed says. “The reality is, if you want to understand how putts break, it isn’t about what’s off in the distance. It’s understanding where the water would run off the green. There are typically two or three directions water can drain, but I’ve built bigger greens where it can run off in five directions. Those are the slopes that are going to do the most to determine how your putt breaks.”

Weed says the key to reading greens is twofold: first, walk up to it from the front (instead of from the side after parking your golf cart or from the back after you leave your buggy). “From 50 yards away, you can really see where the green wants to drain,” says Weed, who also designed TPC River Highlands (home of the PGA Tour’s Travelers Championship) and Michael Jordan’s Grove XXIII. “That is going to give you clues about the predominant break. Second, evaluate your specific putt, keeping in mind the prevailing break as a tiebreaker to make your final read.”

Another factor to consider has nothing to do with topography and everything to do with how grass grows – towards the sun. The ball will roll faster if the blades are leaning away from you (with the grain), and putting across the grain means the ball might behave like a marshmallow thrown into a river. The cross growth on a straight, flat putt can be the difference between rolling one in just off centre or lipping out.

Also, remember that course architects know the misconceptions you have about landmarks and breaks. “We don’t have many more tools in our bag,” Weed says. “Illusion and deception are two useful ones.”

Retire that swing thought of keeping your head down

Looking for the all-time king of golf-instruction malarkey? “Keep your head down” has to be in the conversation. What makes it so damaging is that it’s one of the worst pieces of advice you can get.

“Our coaches will teach about 1.8 million golf lessons in 2023, and about a million of those will start with a player blaming their topped and chunked shots on not keeping their head down,” says Nick Clearwater, GolfTEC’s senior vice-president of player development. “Your bad shots are literally never caused by this ‘problem’. The best players in the world are moving their head upward, and their arms and legs are straightening as they swing through the ball. Yours should, too.”

Instead of working hard to keep your head down – which only serves to restrict your body and slow your arm swing – try this plan of action: make sure to set up so that the ball is in the centre of your gaze. If it drifts too far forward or back, it disrupts your depth perception, and you won’t have as much success swinging freely and making consistent contact. Now make some swings where your only goal is to copy the position of the figure on the PGA Tour’s logo – that’s it.

“The only way to get there is to let your torso move up and your arms and legs extend,” Clearwater says. “Have a friend film you and see how consistently you can get into that position. The closer you are to getting that part right, the more issues you’ll automatically knock out of your golf swing.”

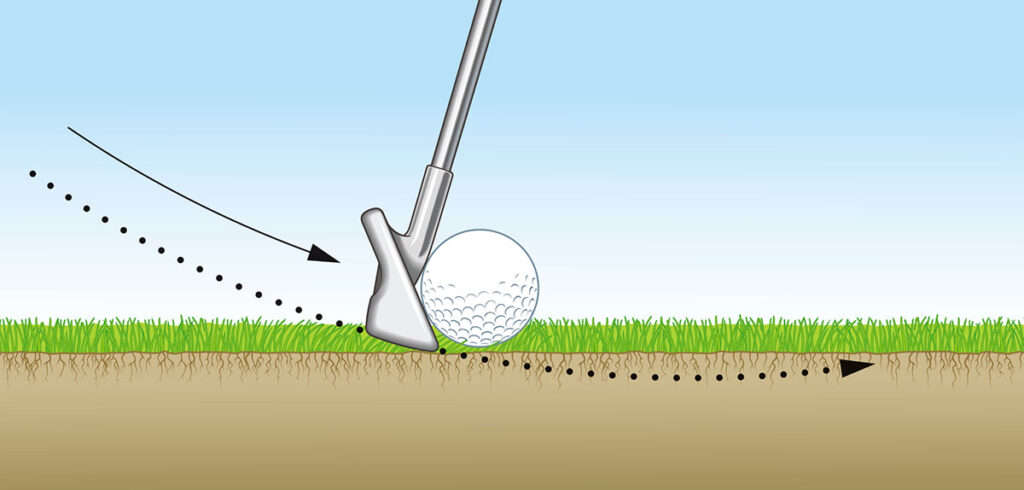

You don’t create backspin the way you might think – And You’re making the COURSE superintendent angry

Every week, hundreds of tour players peel off huge divot pelts as they hit wedge shots that spin back several feet. It’s cool to watch, but it gives many amateur players the wrong idea about what it takes to get some of that ‘sauce’ on their shots. It sends them back to their home courses, chopping down on the ball like David Foster.

“The best players in the world do hit slightly down on the ball, but that downward hit isn’t what’s producing all that backspin,” says Paul Wood, Ping’s vice-president of engineering. “They’re doing it with clubhead speed and friction from clean contact.”

The problem with swinging aggressively down is that it often results in hitting the ground before the ball, piling a bunch of dirt and grass between it and the club.

“Don’t be distracted by the size of the divot,” Wood says. “Pros are hitting the ball first – cleanly – then taking the divot, and its size is usually because they have a lot more speed than average players do.”

The term to understand is “spin loft”, Wood says. It’s the difference between the dynamic loft of the club and its angle of attack as it reaches the ball. Peak spin comes when you have 50 degrees of spin loft, and it can be achieved without tour-pro speed. Just make ball-first contact with a slight downward blow, Wood says.

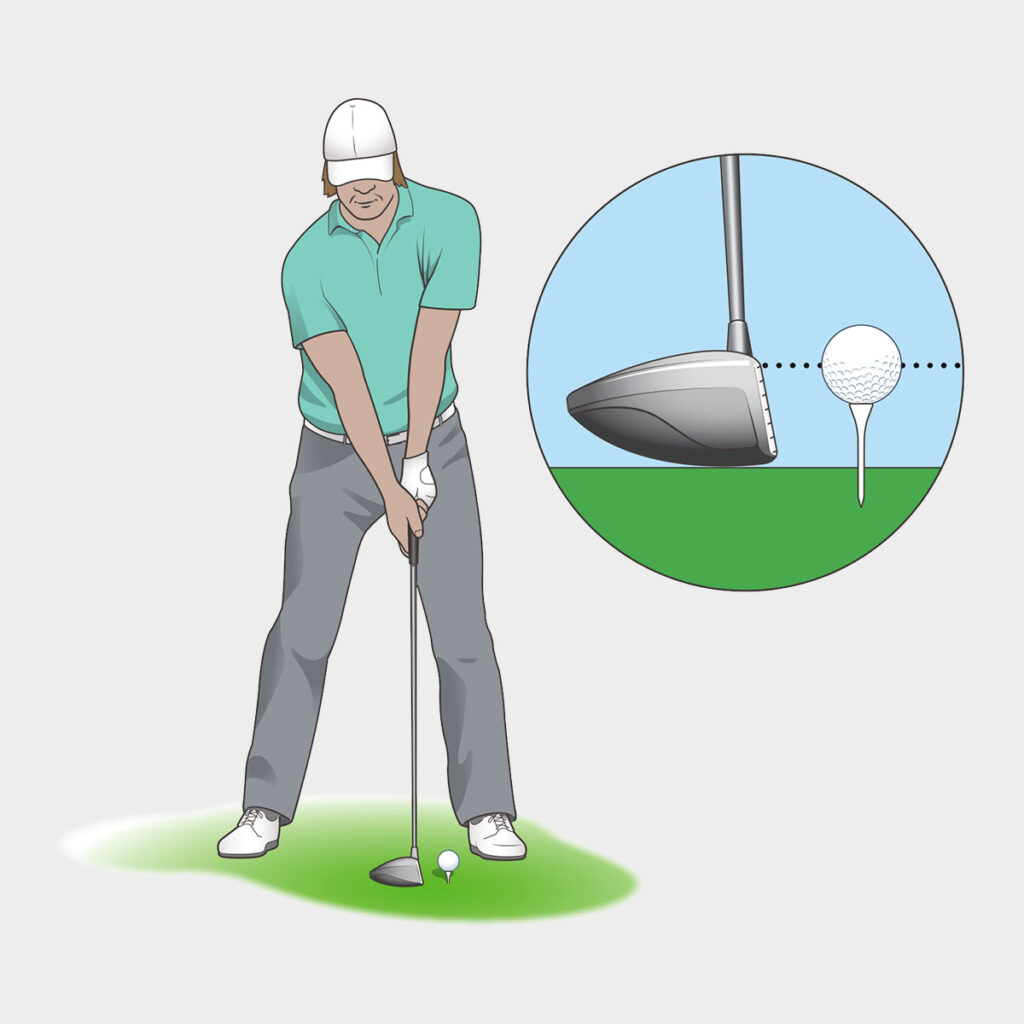

Tee it High and Let it Fly? Not really

Two-time World Long Drive champion Kyle Berkshire swings his driver 145 miles per hour and can generate 230 miles per hour of ball speed. It’s OK for him to tee the ball high and launch it into outer space, but what about you? Berkshire’s coach, Golf Digest 50 Best Teacher Bernie Najar, says you’re most probably dialling up a drive into the rough – or someone’s backyard.

“If your tendency is to swing from out to in like a lot of amateur golfers do, teeing the ball high and playing it more forward in your stance creates a scenario in which you’re going to have impacts that are much more off-centre – both horizontally and vertically on the face,” Najar says. “Catch it too low on the face and you’ll put too much backspin on it. Swipe it off the toe and you’ll have an even bigger right miss. You’re mostly looking at bigger slices or straight pulls.”

To hit your longest drives, get a little more vanilla with your setup, Najar says: tee the ball so that about half of it is above the crown of your driver, and don’t let your ball position drift more forward than the inside edge of your front heel. You’ll be able to sweep it off the tee at an optimal launch angle

for your speed.

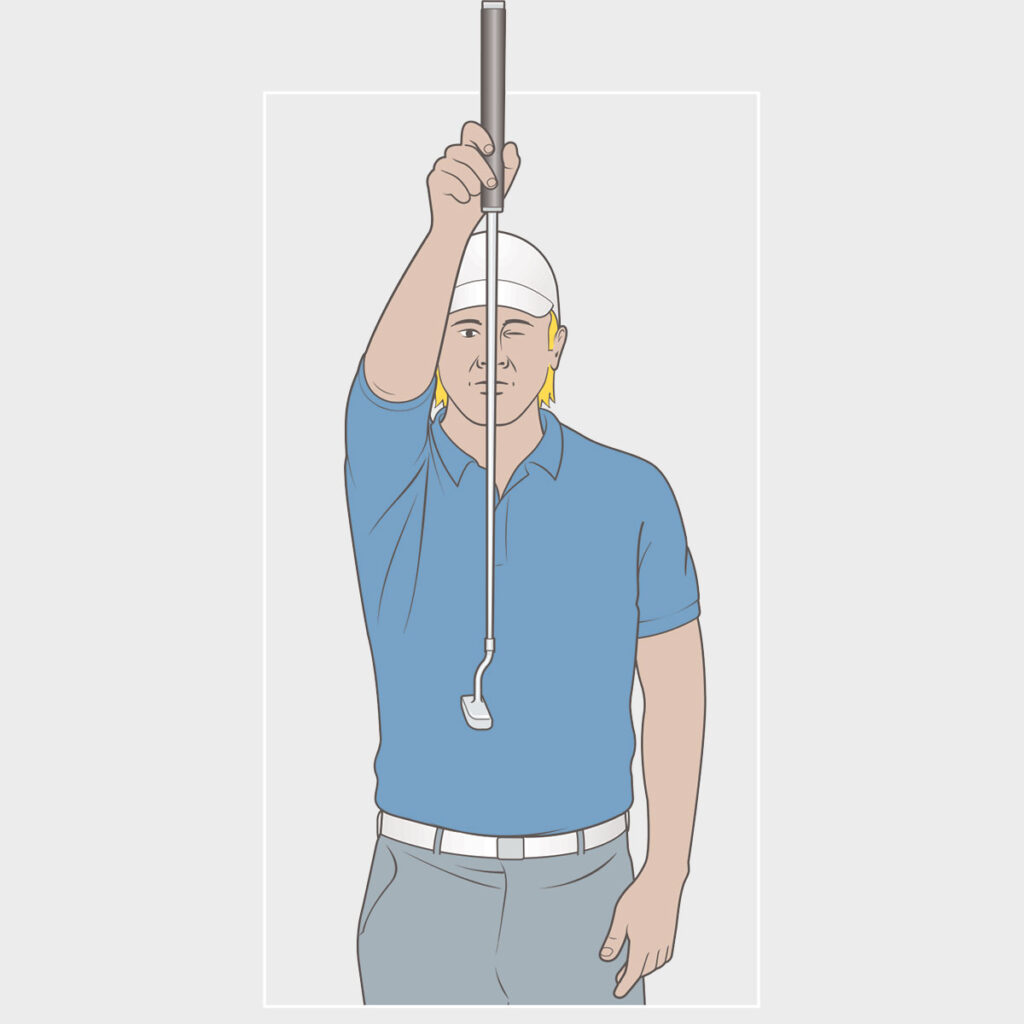

Plumb-bobbing might look cool, but You’re getting only part of the picture

Nothing mystifies reigning PGA of America Teacher and Coach of the Year Kevin Weeks more than watching players stand behind the ball and dangle a putter in front of them as they try to plumb-bob, an old-school method used to ascertain a putt’s break.

“I get that it would be nice to know the overall slope of the putt you’re about to hit, but I don’t know why you would ever take a read like that from the place where the ball is going to be moving the fastest and breaking the least,” Weeks says. “What you need to know is what’s going to happen in the middle of the putt and down by the hole, where the ball is going the slowest and is breaking

the most.”

Even if there was some utility to plumb-bobbing, it would only come if you did it with your putter hanging perfectly vertical and had a non-distorted, accurate view of the line with your dominant eye. Instead of plumb-bobbing, use some of your other senses to get a better idea of what your putt will do, Weeks says. “You can use your feet and your feel to get a better read. Walk slowly from the ball to the cup and back, paying attention to what your feet are telling you. Is it uphill or downhill? How significant is the side slope? Remember, the architect is trying to trick you visually, so you need to do some more work beyond just what your eyes would tell you.”

Once you have a rough idea of the line, walk to the apex of the break [the target, 9;HO>] and read the putt as if you were playing it from there, Weeks says. “Get the speed right and even a bad read will still end up somewhere by the hole,” he says. “Also, pay close attention to what the ball is going to do as it slows down near the cup. That’s great intel for what you need to do next if you miss.”

Illustrations by George Retseck