[PHOTO: Matthew Lewis]

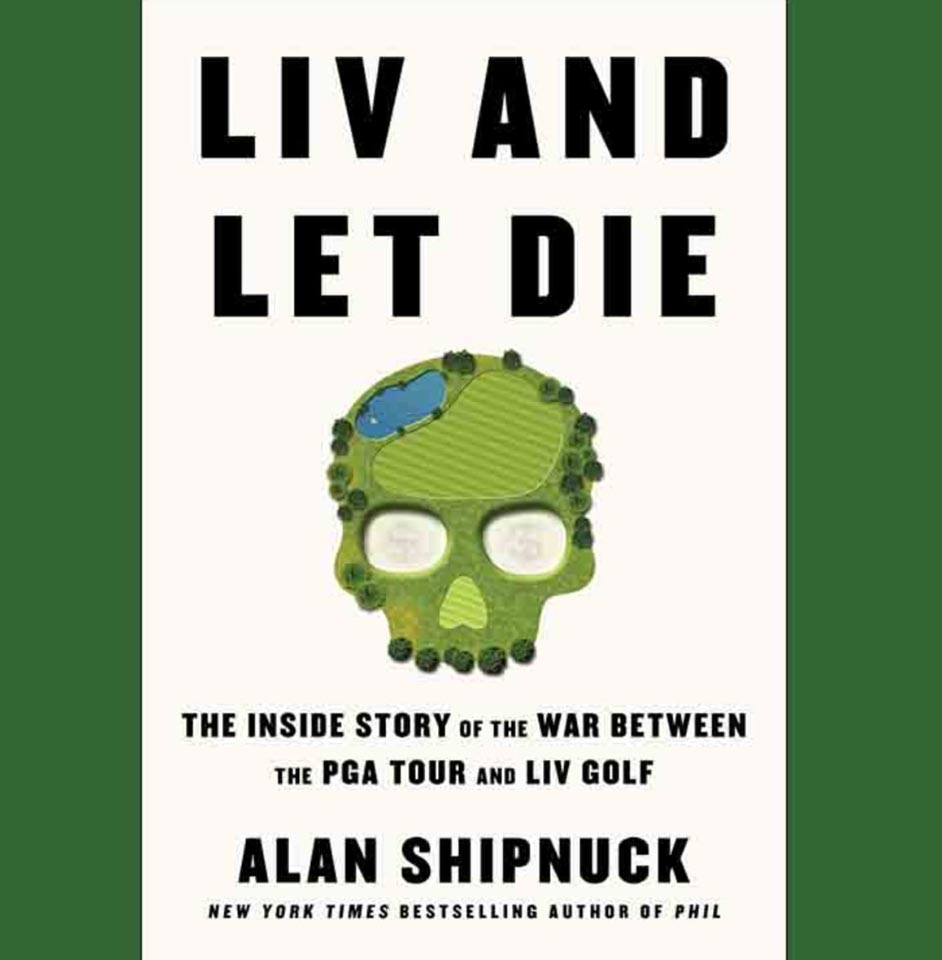

In his new book LIV and Let Die, released this week, Alan Shipnuck spends 325 pages telling the story of LIV Golf from its birth to the point in the story some weeks ago when the manuscript was due. That makes it incomplete, but if you read it now, you’re not going to miss much—he covers everything through the big merger, and if there are one or two minor details missing from the ensuing quagmire, it won’t spoil your fun. The completed work also represents an impressive feat of speed from Shipnuck, whose management negotiated the book deal without him knowing, threw the contract on his table at a restaurant in New York City last June, convinced him to sign and gave him about a year to produce a book on the most incendiary story in the history of golf.

The finished product, which follows on the heels of his New York Times bestseller Phil, has a few different faces. The opening third provides a thorough overview of the history of LIV Golf, and when I say that word “history”, I mean the winding kind that harkens back to the great schism that created the PGA Tour, the origins of Greg Norman’s antipathy for that organisation and, most fascinating of all, the evolution of the House of Saud, which united Saudi Arabia in 1932 and then, in the game-changer of all game-changers, struck oil in 1938. Shipnuck does an admirable job weaving these historical threads and manages in the midst to tell the tragicomic story of Andy Gardiner, a man who had a good idea, the Premier Golf League, and very little real power to make it come alive. But it was Gardiner’s idea, having left Gardiner behind, that took root and became LIV Golf in the hands of some people with a whole lot of power. It’s a terrific history, and even if you think you know everything about the LIV Golf melodrama—indeed, even if you’ve been immersed in it far too long—you’ll learn something.

It’s the part of the book I enjoyed the most, and it also happens to be the part that will generate the fewest headlines. After all, who cares about sweeping historical narratives that, via the mechanism of capitalism, define and constrict our lives when you have Brooks Koepka taking a potshot at Justin Thomas, or Claude Harmon III accusing Brandel Chamblee of performing metaphorical fellatio on Rory McIlroy and Tiger Woods? (Not at the same time, to be fair.) There’s a lot of that here; the book is gossipy as hell, and the gossip is fun, and it’s absolutely going to be one of those texts that people use to rail against as the Fall of Journalism while they secretly consume it in greedy chunks. Shipnuck, for all his storytelling ability—hell, as part of his storytelling ability—knows how to dish out the sugar, and in service of that, he’s very good at getting people to talk to him anonymously.

Oh yes, anonymous sources! They exist! But how do we feel about this? There’s a knee-jerk reaction against the practice that rises like a predictable tide whenever a writer makes use of them effectively. I happen to think that a free press needs anonymous sources to function at full throttle, especially when it comes to the big, combustible stories where the big players need that safety net. That said, I’m not immune to the argument that, say, using an anonymous European Ryder Cupper to call McIlroy a dirty hypocrite isn’t quite equivalent to Deep Throat bringing down Tricky Dicky. Viewed in a certain light, it can even look a little cheap. But I don’t know how you distinguish the two tactics from a purely procedural angle—if one’s allowed, the other has to be, right?—and my guess is that Shipnuck would defend it on the merits, because it undoubtedly adds perspective to his story. The Rory slander might be racy, but it also represents what a certain sector of the LIV population fervently believes. Plus, it comes backed with financial receipts, and when you’re telling this particular story, is that not worth printing even if the slanderer won’t be named?

I can’t make my way to moral condemnation on this front, although it’s a more complex debate than we have time for here, with lots of nuanced situations that may change the calculus. In any case, the sources knew the stakes; full disclosure, Shipnuck asked me to shed some light on a very small part of his book, I declined twice, and lo and behold, I did not appear in the book as either a named or unnamed source. (Neither did Eamon Lynch, who declined in a more emphatic fashion at a bathroom urinal… a detail that, of course, makes the book.)

So, is it a success? As a measure of how quickly you’ll read it if you’re interested in any of this stuff, yes. (I flew through it in one long train ride.) The writing is classic Shipnuck: quippy, sometimes funny and always most concerned with pushing the story forward. The pace is brisk; he will never bore you. Certain characters are painted with broad strokes, but when you’re trying to unravel the Gordian Knot of LIV Golf without putting readers to sleep, that strikes me as forgivable.

If there’s a critique to be levelled here, it’s that the framing feels off at the start. In the prologue, he introduces Greg Norman, unravels his antagonistic history with the PGA Tour and leaves us with the impression that the story of LIV is in some ways the story of one man’s monomaniacal revenge drive. This makes for a compelling set-up, and does its job to build anticipation, but ultimately, I think this is “poppycock”, to use a Shipnuck-ism. I think Shipnuck does too, because by the end of the book, on page 309, he spells out the real message: “The overarching lesson in this war between the tours is that money always wins.” And then again, on the penultimate page, referring to Chamblee: “None of his critiques had been wrong on the merits, but like another ideallist—McIlroy—Chamblee failed to recognise that his side never had a chance. Money always wins.”

The truth is that for all Greg Norman’s vengeful impulses, he’s never been much more than a useful pawn in a much larger story, and that story is about as fatalistic as they come. Shipnuck tells a good tale, but it’s not a particularly uplifting one, and you can see why he leaves the ugly conclusion for the end. We might have been blinded by the dramatic twists and turns along the way, but this saga was written in stone from the very beginning. And even though Shipnuck’s book was published before the resolution, the lack of closure doesn’t matter: we already know the ending.