We’re talking course set-up. At Carnoustie. It’s a combination that immediately brings to mind the 1999 Open Championship, a horror show defined and defiled by the long, thick and suspiciously verdant green grass that all but covered the ancient links. All of which sounds nice from a distance. But it wasn’t pretty up close.

Sergio Garcia left the course in tears after shooting 89 in the opening round. Australia’s Rod Pampling led the field after the first day – and missed the cut 24 hours later. Then there was Greg Norman. Having missed the 17th fairway by less than one pace, one of the most powerful players the game has ever seen was able to move his ball only a few feet with a full-blooded swing.

The climax, of course, was all but unbelievable. No one who witnessed it will surely ever forget the triple-bogey 7 Jean Van de Velde wretchedly posted on the 72nd hole. It was a tough, albeit fascinating, watch. A 6 would have won the Frenchman the claret jug that Paul Lawrie ultimately claimed.Things are different now, though. In the wake of that much-maligned championship, officials with the R&A assumed control of the sometimes dark art that is course set-up. Today a lot of thought goes into a) producing a good challenge for the best players (male or female) in the world, and b) ensuring that the features of a course – fairway bunkers and greenside slopes and undulations, by way of example – are brought into play.

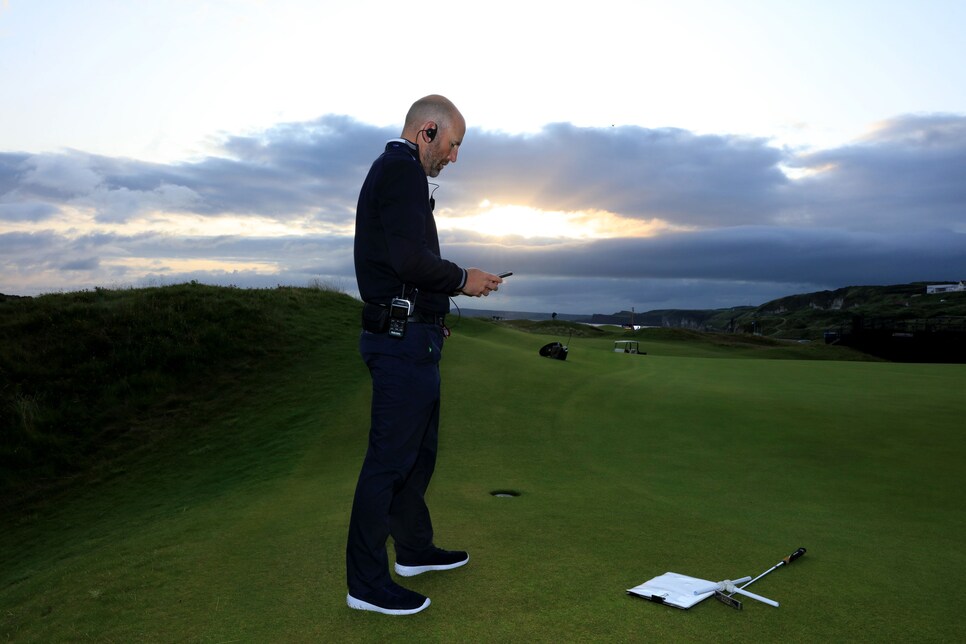

“Over the course of four championship days, our aim is to produce a reasonably balanced setup that provides a nice sense of variability during the course of each round,” says Grant Moir, the R&A’s director of rules who will lead the course setup team for this week’s AIG Women’s British Open at Carnoustie.

Which provokes an obvious question: given the difference in how far the game’s leading women hit golf balls in comparison with their male equivalents, what, if any, adjustments will have to be made when setting-up the course?

“We’re not really in the business of trying to get the women hitting the same clubs as the men into the greens,” Moir says. “It can be done. But it would probably need more of a downward adjustment in yardage than we are prepared to make. Or want to do. Besides, the games are slightly different. Even if one of the women is hitting two clubs more with an iron, they can be just as accurate.”

Distance apart, the biggest gender-based disparity is that the women are able to create less spin on their approach shots. In turn, that has implications for pin positions. If the vast majority of players are going in with, say, a 4-iron, there is no point in sticking a flagstick only three yards over a bunker. That would be silly, as would excessively fast putting surfaces in a place with the wind potential of Carnoustie.

“We want to be able to use as many areas of the greens as we can,” Moir says. “Excessive speed only reduces our options. We tend to work towards 10 feet on the Stimpmeter. It’s a nice middle ground. We can adjust downwards or upwards from there.”

In some ways, Moir has more fun setting-up a course for women. For men, there isn’t much thought required when it comes to most tees, take them back as far as possible. But for the women, there is more scope to move things around. Every tee on the course is in play, albeit Moir searches for those that best bring in the hazards and features on each hole.

“Typically, I look to have the fairway bunkers placed around the 260, 265-yard range,” he says. “That’s the number in my mind. But it’s only a starting point.”

Speaking of which, what about the rough that so scarred that ’99 Open? How intimidating is the links many regard as the most difficult on the Open rota going to look from the tee?

The answer can be summed up as “no more than normal”, which is still, in places, pretty frightening. For the Women’s Open there will be three cuts of rough. The first is your classic “semi-rough”. It will be pretty short and designed primarily to take the spin off the ball. Playable, but liable to cause a loss of some control.

Then there’s a second cut. It will either be cut slightly higher, or cut then allowed to grow naturally during the week. Either way, the idea is to create indecision. Moir wants players to be unsure as to exactly what they are going to get, adding nicely to the inherent randomness of links golf.

Beyond that, there will be what the R&A calls “unmanaged rough”. That is basically left to nature.

With so much going on in the run-up to a championship (course visits typically start up to two years in advance), communication is vital. The players need to know what R&A officials are doing with the course, and why they are doing what they are doing. Which is why every player will receive an information sheet when they arrive. That provides details on course setup. If different tees might be in play, for example. Heavily stressed is the ability of any player to raise concerns over anything they see. It could be a lack of sand in a bunker. Or a run-off area that has been damaged during practice. Whatever, the players are given numbers to call and names to contact.

“We also get out there during practice days to engage with them and the caddies, just to get general feedback,” Moir says. “If a general concern arises from a number of players, we hear about it pretty quickly. That’s important. If we keep things to ourselves, people inevitably make assumptions that might not be factual.”

OK, some specifics. Are there any holes at Carnoustie where Moir can have some fun with the setup?

“The focus when talking setup tends to be on par 3s. I enjoy the ability to move tees around on those holes. I’m a big fan of the eighth hole here, with the boundary fence on the left and the bunkers on the right. It’s a challenging hole, especially when the ground is firm. There are some pin positions I would only use if we move the tee up a little. So we’ll likely do that, depending on the weather.

“The 11th hole is one we will think about playing as a driveable par 4,” he continues. “There is a tee in front of the burn there. I like the way that hole sets up for those who want to have a go from the tee. There is potential for an eagle if the drive is long and straight. But it is also easy for me to put the pin in a place where the player who chooses not to ‘take on’ the drive will find it hard to make birdie.”

Then there is Van de Velde’s golf grave, the 18th. Like most fans, Moir is looking forward to seeing the top women taking on what is perhaps the most fearsome finishing hole in golf. It’s a hole where no one is ever totally confident until the ball is in the cup. There is trouble off the tee. There is trouble on the second shot. Even laying up short of the Barry Burn is fraught with danger. Ideally, Moir wants to see the players going in with a longish club.

“That’s where the real challenge lies,” he says. “The 18th requires a really good drive, then a really good approach. It’s a hole made for drama. I like that scenario. We never have a winning score in mind. All we’re trying to do is provide a challenge that identifies, not only the best players that week, but the best players of the time. We simply want to provide an appropriate challenge for a Major championship.”

All of which sounds a lot better than 1999.

TOP/MAIN PHOTO: David Cannon